by HALEY MLOTEK

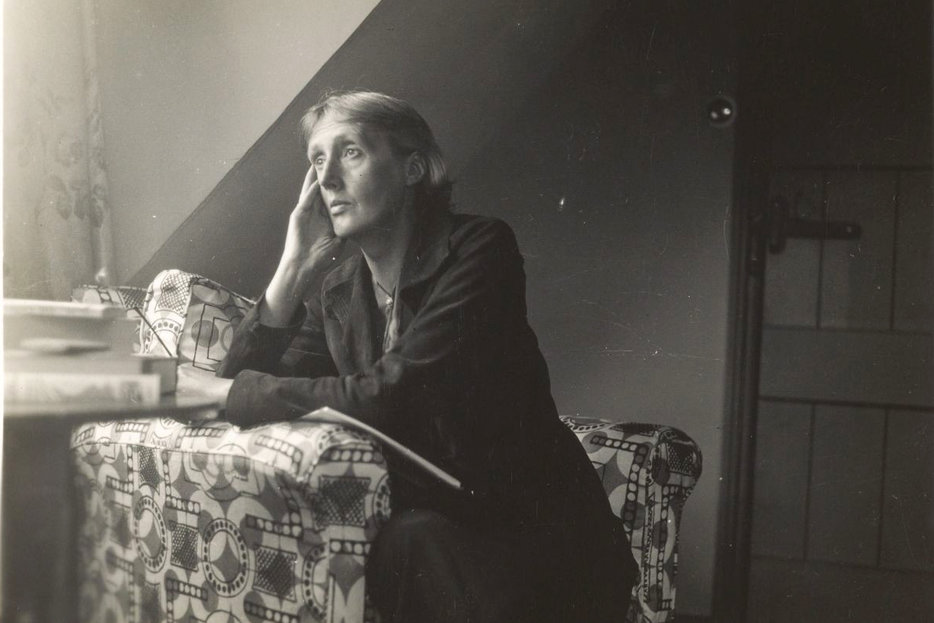

Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf

Did these women hate themselves, or did they write about a world that hated them?

I was once asked to write an essay that would answer a question: why do so many women writers hate themselves? Self-loathing, they called it, and she was the self-loathing women writer.

I did not like this question, but I did recognize it. I could have given a simple answer in a straight line, cataloguing the many instances of women who wrote about their selves and their hate, and said that this approximated self-loathing. I could have written about women who write about mutually masochistic affairs with people they don’t love or can’t trust, or the posthumous collections of women who lived sad lives and died sad deaths, or I could have written about novels or poems or memoirs about addiction, depression, abusive childhoods, recollections of grief. I could have looked at honest admissions of guilt or regret or sadness or anger and used those emotions to say there, I found her, there’s the woman who hates herself.

But did those women hate themselves, or did they write about their relationship to a world that hated them? Wasn’t self-loathing the symptom, rather than the condition? And anyway, why did we have to consider it in terms of a diagnosis? I thought the inquiry was a statement trying on a question for size, and said as much. I went looking for an answer that would improve the question, which either did not exist or I was not able to find.

Couldn’t it be true that the question was incomplete? Weren’t there other questions—not necessarily better, just other—that could or should be asked before we decided that this determination was our question? The essay went nowhere, but I sometimes think about that woman writer who hates herself, in case she’s still out there, waiting to be found.

*

The canon of art history as it stood then (and now) was almost exclusively white, male, and Western, or similar designations we use when talking about people who have personal and professional power over others. And so the standards of greatness were ones that, by design, excluded anyone not of those categories. Meanwhile, the conditions necessary to make art—as Virginia Woolf wrote in 1929, the rooms of their own and the five hundred pounds a year—were not available to women, again by design. Men made women into wives because they needed their labour. Wives were the proofreaders, editors, cooks, babysitters, the names thanked in the acknowledgements of their husband’s books. If they were lucky they got to be muses, forever lying down on canvas. This is the foundation of culture, and also, of everything else: a subjugation based on definitions of gender, race, and class, so that one kind of man can succeed.

“Women,” whatever that means as an identifier or category, is not enough of a link between all the people who could be labelled as such. As Nochlin wrote, when considering the work of Artemesia Gentileschi, Mme. Vigée-Lebrun, Georgia O’Keefe, Helen Frankenthaler, Sappho, Jane Austen, Emily Brontë, George Eliot, Virginia Woolf, Sylvia Plath, Susan Sontag, just to name a few of her examples, they “would seem to be closer to other artists and writers of their own period and outlook than they are to each other.” Similarities of subjugation are no substitute for solidarity; comparisons have a way of enforcing hierarchies. Still, somehow, we are asked to think of women as a unit, and whatever greatness they achieve is made the proof of an artistic equation.

Hazlitt for more