by ANTHONY GOTTLIEB

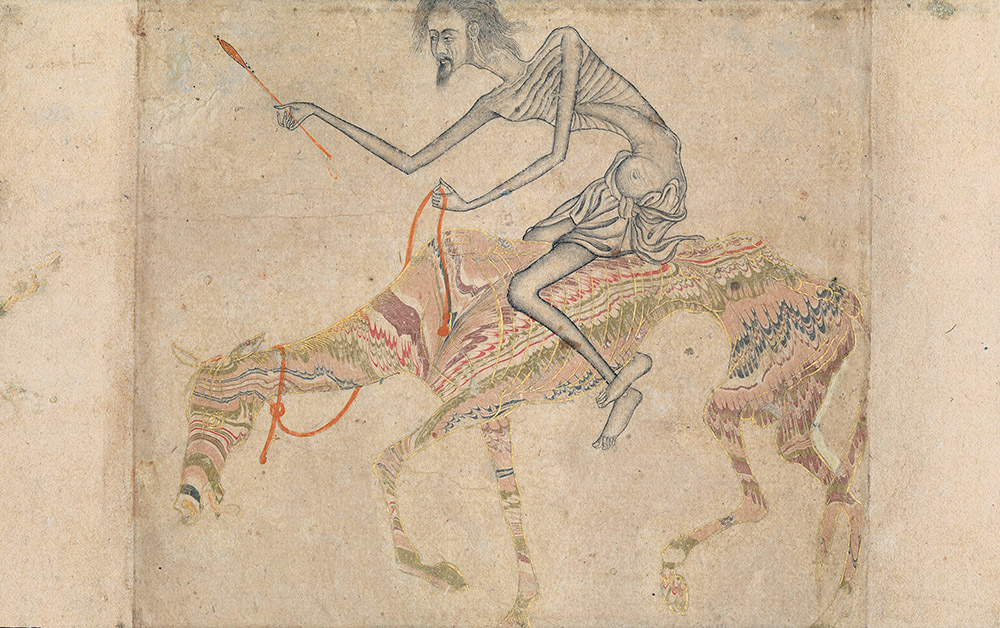

Emaciated Horse and Rider, India, c. 1625. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1944. Symbols of bodily desire in Sufi imagery, horses are often shown starved and beaten.

Emaciated Horse and Rider, India, c. 1625. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1944. Symbols of bodily desire in Sufi imagery, horses are often shown starved and beaten.

The correspondence of René Descartes and Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia—a debate about mind, soul, and immortality.

There is an “official theory” about the nature of minds that “hails chiefly from Descartes,” wrote Gilbert Ryle, an Oxford philosopher. According to the theory, each person has a mind that is a private, inner world. It has no spatial dimensions and is not subject to laws that govern physical objects, yet it is mysteriously connected to a material body during a person’s earthly life. Ryle dubbed this “the dogma of the Ghost in the Machine.”

People have not always thought of the mind and the body in this way. Homer’s heroes are not depicted as composites that are only partly physical. Their awareness, intelligence, and other mental activities are part of their bodily lives. And although the shades of the dead lurk in the Homeric underworld, these etiolated creatures are little more than fading echoes of the living. Some later Greek philosophers explicitly stated that the soul is made of physical stuff. For Democritus, it was tiny units of solid matter. For the Stoics, it was a mixture of fire and air.

Unlike Homer and the Greek materialists, Plato did believe in something like René Descartes’ ghost in the machine. A person has an inner rational self, according to Plato, which can escape its bodily imprisonment with its powers intact. Yet Ryle was right to single out Descartes even though parts of the “official theory” can be traced to Plato. Descartes sharpened the concepts of mind and matter, crystallizing ideas that took shape in the seventeenth century and giving us the modern form of the so-called mind-body problem.

In his Meditations on First Philosophy, published in 1641, Descartes announced that he was essentially a thinking thing: “Thought…alone is inseparable from me.” There is an outer world, which includes my body, but I could still exist even if it were all destroyed. And what exactly is a thinking thing? Something that is aware. Descartes explained that by “thought” he meant “everything that is within us in such a way that we are immediately aware of it.” This included sensation, will, intellect, and imagination. Thus Descartes made consciousness the distinguishing mark of the mental.

Imagination continually outruns the creature it inhabits.

—Katherine Anne Porter, 1949

He also merged the concepts of mind and soul. The “mind” was “the principle in virtue of which we think,” and a person’s soul was his or her mind. This was a novelty since in medieval science and philosophy, the soul was largely regarded as what animates inert matter. If a body died, it was because its life-giving soul had departed. But for Descartes it was the other way around. If the soul departed, it was because its body had broken down.

Laphams Quarterly for more