by JOHN BERGER

PHOTO/The Paris Review

PHOTO/The Paris Review

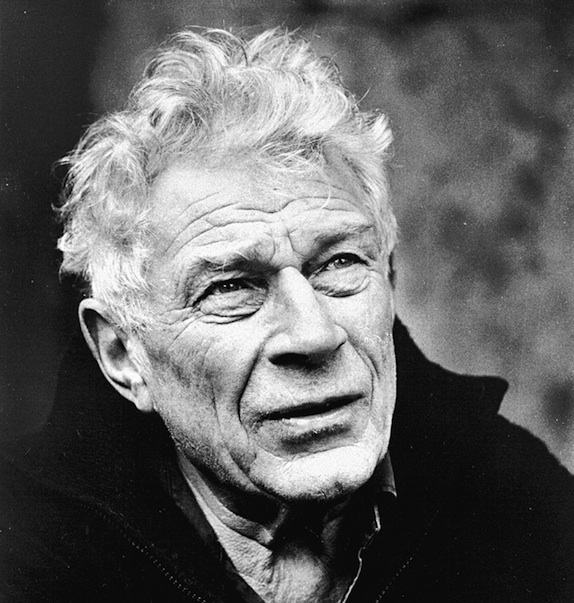

He has fought alongside guerrillas in the mountains many times in at least two continents. He’s also an excellent cook. He will happily spend an entire day preparing an evening meal for friends. His name is Eqbal Ahmad. Once when he and I were cutting up vegetables for a curry, he told me a story.

It began in 1947. Eqbal was thirteen years old. His voice had begun to break. Sometimes he spoke as gruffly as a man, at other times he spoke in a boy’s falsetto. He couldn’t control it. But he already had a man’s decisiveness, he was already at risk like a man. I imagine the knowledge of that risk was in his eyes but I didn’t know him then.

With independence, India was being partitioned. Twelve million people were on the roads, going in both directions, seeking safety. Eqbal’s family had lived as Muslims for generations in India but now his elder brother decided to take the family to the newly created Pakistan.

The boy’s mother refused to leave. Only mothers who are widows can become as immovable as she did. The rest of the family took the train for Lahore. In Delhi they learnt that the train would go no further: the fighting of the civil war was too dangerous. Everybody was lodged in a refugee camp. Eqbal’s brother, who was a senior civil servant, telegraphed for a plane to come and rescue them. A whining man, begging for opium in the camp, caught Eqbal’s attention. Misery importuning misery, he thought. Some youngsters pushed the man aside. Ay! Charsi! they mocked. Ay! Charsi! Opium-eater who lives in a cloud of smoke!

Finally the plane from Pakistan arrived. It was an ex-RAF Fokker. At the airport the two brothers were the last to embark. Every place was already taken.

You can fly in the cockpit with me, sir, the pilot shouted to his brother.

No, we’re two, there’s also Eqbal.

Then would you like me to tell somebody to get down, sir?

No, take Eqbal.

It was then that the thirteen year old revolted. He ran across the tarmac away from the plane.

Go, he shouted, go! I’m going to walk.

His brother, perhaps because he wanted to accompany his wife and small children, perhaps because he knew how obstinate and bone-headed Eqbal could be, climbed up into the plane and, standing by the still open door, said: All right, but take these! Whereupon he handed down a .22 single-barrel hunting gun, an ammunition belt and a 100-rupee note. Stay here and wait for the next plane, he added. Finally the Fokker took off.

Eqbal went to a restaurant and ordered in his gruff voice an elaborate dinner. The bill came to 10 rupees. Then he walked towards the Muslim quarter of Delhi. He could see in what direction to go, thanks to the minarets. He took the wide streets. Muslims in the city were being killed but with the rifle slung across his back he felt confident.

The following day he joined an immense column of refugees who were setting out to walk the several hundred kilometres to Lahore. The same afternoon, when the shadows were long, a portly middle-aged merchant walking behind Eqbal pointed at him and said to his companion that a youngster of his age should not be allowed arms. Let him at least be a gun-carrier, said the companion, like that we have less to carry.

Indian Cultural Forum for more