by PERRY ANDERSON

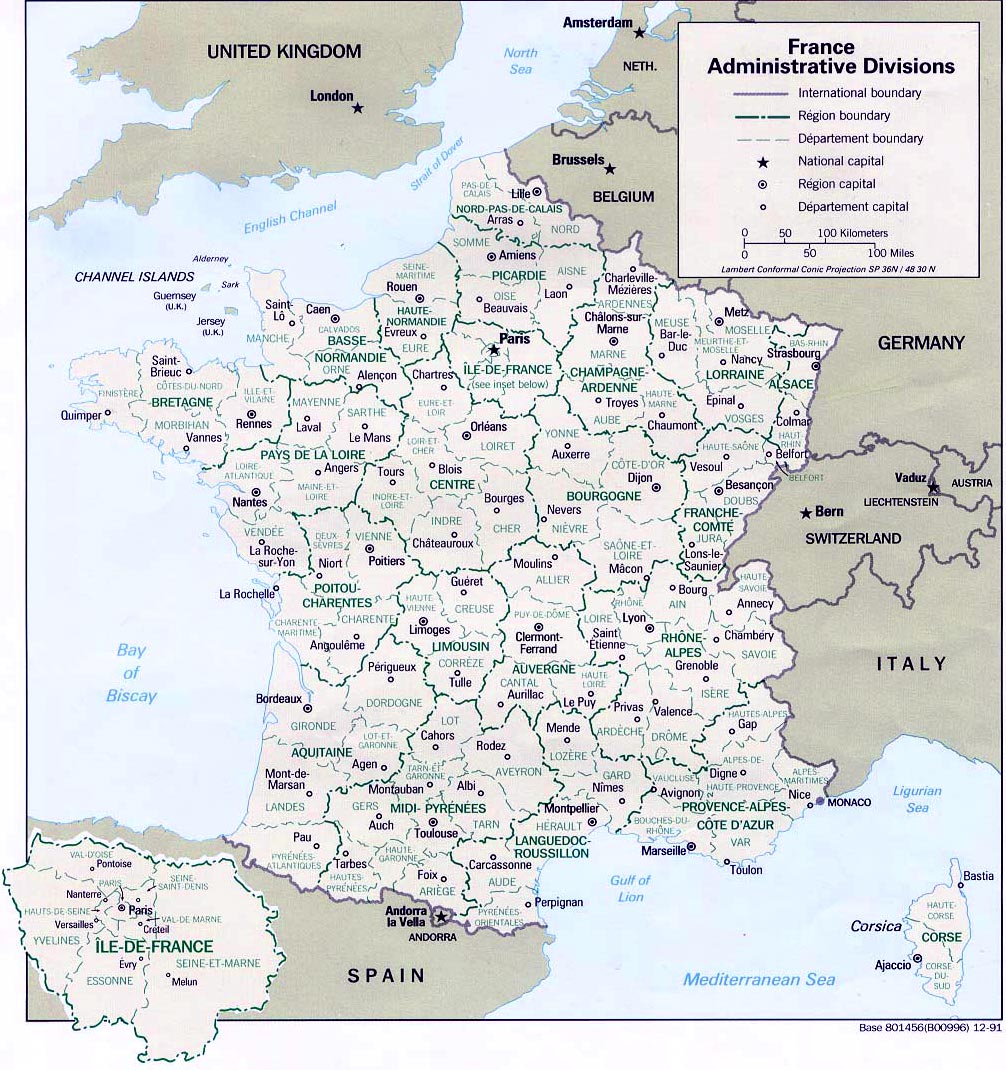

MAP/Carte De France

MAP/Carte De France

The French Spring

France, geographically and politically the hinge of the European Union, where its northern and southern tier join, has undergone a more drastic change of position within it than any other member state. Germany, already with the largest economy and population before unification, has since become—once again—the dominant power of the continent, and as its franker spirits make no secret, hegemonic in the Community. Spain, long marginalized by poverty and dictatorship, has lived entry into the Community as status-promotion to European prosperity and respectability. These have reason for satisfaction with the eu. Italy less so: its economic slippage under the single currency, however, has not substantially altered what was always a supporting rather than leading role in the Community. France, on the other hand, which was once premier among the six founders—capable under De Gaulle of bending the other five to its will, French functionaries and language first in influence and use in the Commission, and down to the turn of the eighties still diplomatically senior partner with Germany—has seen a remorseless fall from former heights. In part this was an inevitable consequence of German reunification, which automatically gave the Federal Republic a still greater demographic and economic advantage. But in larger measure its sources were endogenous.

The indices of the country’s loss of standing, most of them well advertised in native debates, are legion. Many go back to the nineties, but have become starker since the crisis of 2008. Economically, growth has crawled, averaging less than 1 per cent a year; unemployment increased to 10 per cent—among youth 25 per cent; [1] the budget not been in the black for over forty years; public debt risen to 96 per cent of gdp; per capita income scarcely moved. Diplomatically, Paris has more and more taken its cue in Europe from Berlin and in the world beyond from Washington, its elites barren of significant independence in either arena. Culturally, English has become the lingua franca of the Union, official and popular. Socially, no other large country in the Eurozone has seen such levels of social and racial unrest, or consistent expressions of popular dissatisfaction with the state of the nation. For years now, with the briefest intermissions, morosité has become a settled mood.

1

Politically, the Fifth Republic created by and for De Gaulle, with a unique concentration of executive power in the Presidency and a legislature rigged to exclude trouble-makers, functioned more or less smoothly for thirty years after his death, down to the end of Mitterrand’s time in the Élysée. By then the era of fast growth and rapid rise in living standards that had underpinned its original success was long over, and the effects of the global downturn since the mid-seventies were beginning to tell. Mitterrand’s sharp turn of 1983, abandoning public spending to prime the economy for austerity to stabilize the currency, talk of socialism for rhetoric of financial discipline, was widely greeted as putting the political system on a sounder basis. In neutering French communism as a helpless junior accomplice to the change, and discrediting the pernicious revolutionary strain in the country’s culture, he had laid the foundations of a stable Republic of the Centre: no longer dependent on the individual charisma of a national hero who was distrustful of parties, but now solidly anchored in a cross-party ideological consensus that capitalism was the only sensible way of organizing modern life. With the pcf at last eliminated as any serious presence from the scene, France could look forward to the kind of alternation between a Centre-Left and Centre-Right, differing on details but agreed on essentials, that was the certificate of a liberal democracy.

So, on the surface, it came to pass. At the Élysée, Mitterrand from the former was succeeded by Chirac and his faithless minister Sarkozy from the latter, followed by Hollande from the former: nineteen years of presidential rule by the Centre-Left, seventeen years by the Centre-Right. Until 2002, when the Presidency was abbreviated from seven to five years, making elections to the executive and legislature coincident, there was even alternation within alternation—‘cohabitation’—as one side captured the Premiership with a majority in the National Assembly while the other continued to hold the Presidency: Chirac and Balladur under Mitterrand, Jospin under Chirac. But below the surface, for deep-lying cultural reasons, the equilibrium was always less stable than it seemed. From the eighties onwards, as elsewhere in the West, the continuous imperative of the time was neoliberal radicalization of the operations of capitalism: deregulation, privatization, flexibilization. In France, this was an agenda calculated to provoke tensions within the electorates of both Centre-Right and Centre-Left. [2]

New Left Review for more