by SHARMILA RUDRAPPA

IMAGE / Columbia University Press

IMAGE / Columbia University Press

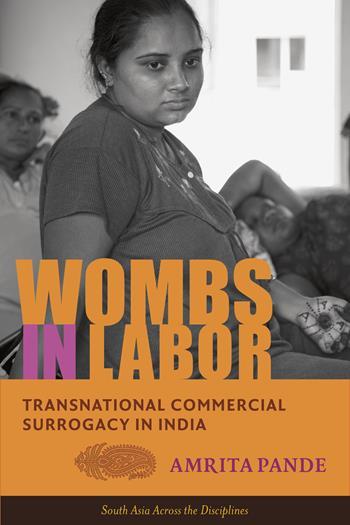

Amrita Pande. Wombs in Labor: Transnational Commercial Surrogacy in India. New York: Columbia University Press, 2014. 272 pp. $90.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-231-16990-5; $30.00 (paper), ISBN 978-0-231-16991-2.

International Surrogacy

As a researcher myself on reproductive politics in general and surrogacy in particular, I cannot emphasize enough the impact sociologist Amrita Pande has had on debates surrounding global surrogacy through her various articles published on the topic since 2009, and now collated into this more comprehensive monograph, Wombs in Labor. Between 2002, when India first legalized commercial surrogacy, to 2016, when Modi’s government banned commercial surrogacy altogether, cities such as Anand, Bangalore, Delhi, Hyderabad, and Mumbai were multimillion-dollar nodes on a global infertility industry that drew clients from Australia, Britain, Egypt, Germany, Israel, Spain, and the United States.

Spanning academic discussions to popular culture (she is featured in an Indo-Norwegian Dutch play titled Made in India—Notes from a Baby Farm), Amrita Pande’s is among the first ethnographies on the topic based on fieldwork begun in 2006, before the phenomenal rise of surrogacy in India. As Pande notes, when she first began fieldwork at what she calls “Armaan clinic,” the clinic had been instrumental in the birth of perhaps ten surrogated babies, but that was to soon change. By March 2013 “Armaan clinic” had announced the birth of the 500th baby through surrogacy, and by December that year the 600th invitro-fertilized baby was delivered in “Armaan” (p. 19). An ethnographer’s sense of ethics keeps Pande from revealing her fieldwork site; she says that her study is located in the uncelebrated Indian city named “Garv,” where every auto-rickshaw driver knew that “Usha Madam” was very famous and that all foreigners went to her (p. 37). Yet, tying together all the details provided it becomes clear that readers are being led to India’s surrogacy doyen, Dr. Nayna Patel, and her much-celebrated and equally vilified Akanksha Clinic in Anand, Gujarat, which is regarded as ground zero for Indian surrogacy.

Though recruitment, labor practices, and class locations of surrogate mothers vary vastly from Indian city to city, as evinced by studies on surrogacy in Bangalore (Sharmila Rudrappa, Discounted Life: The Price of Global Surrogacy in India, 2015), Delhi (various publications by SAMA), and Mumbai (Daisy Deomampo, Transnational Reproduction: Race, Kinship, and Commercial Surrogacy in India, 2016), Dr. Patel’s model of strictly regulated surrogacy dormitories, wage structures, and recruitment strategies has come to stand as the norm for how to understand surrogacy in India. That itself makes Amrita Pande’s book a noteworthy contribution; she provides a rich and detailed ethnography of a surrogacy clinic and its surrogate mothers in the very place that came to epitomize commercial surrogacy in India.

Based on fieldwork conducted between 2006 and 2011, with in-depth interviews mostly in Hindi with fifty-two surrogate mothers, their husbands, and in-laws; twelve intended parents; three doctors; three surrogacy brokers; three surrogacy hostel matrons; and several nurses, Amrita Pande provides thick descriptions of how surrogate mothers are recruited, how they are disciplined into industrial labor practices on the shop-floor in the surrogacy dormitory, how they perceive themselves as engaging in not wage labor alone, but divine labor, how they are cast as disposable workers, and how they reinsert themselves into the labor process by establishing kinship ties to clients and the surrogated babies. Given its ethnographic focus the monograph might seem to be a “narratives only” sort of account of surrogacy, but Pande provides a rich theoretical exegesis on how unpaid reproductive labor, that is, pregnancy and childbirth, become commodities that can be bought and sold on the market.

…

Yet, like all other capitalist labor processes, surrogacy is premised on worker disposability. That is, all that matters is the end product, which in this case is a baby and the clients’ entry into parenthood. The surrogate mothers, however, reinsert themselves into the labor process by emphasizing their unique characteristics, because after all, why else would the clients have chosen them if not for their specialness? They emphasize that they are not abstract wombs, but unique individuals who share exceptional bonds with client couples. Moreover, some claimed they received better wages because of their distinctiveness. Puja says of her client, “Mrs. Shah, the woman, is also a Brahman [upper caste]. Maybe that’s why she liked me, because I am clean…. Doctor Madam says to me, ‘Why can’t you get me ten, fifteen more Pujas” (p. 138). Surrogate mothers constructed kinship ties with clients, especially intended mothers, in “ties of ‘sisterhood’ that seemingly cross all borders in Garv” (p. 164).

Humanities and Social Sciences Online for more

South Asia Citizens Web for more