by JACK PEACOCK

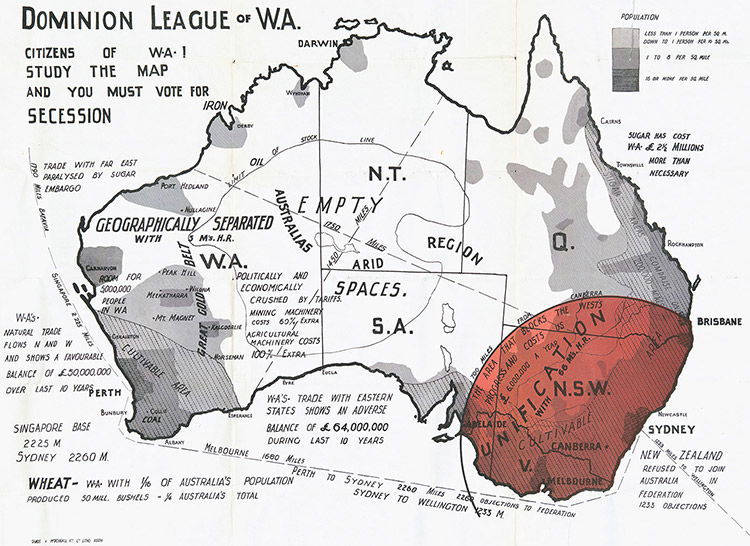

‘Westralia Shall Be Free’: Dominion League of Western Australia Secession Map, 1930s

‘Westralia Shall Be Free’: Dominion League of Western Australia Secession Map, 1930s

This year’s referendum on the UK’s membership of the European Union and Scotland’s 2014 independence vote were just the latest in a long line of similar events. While Scotland joined Quebec (1995) in voting for the status quo, others such as Norway (1905) and Montenegro (2006) voted in favour of separation. One theme that seems common to all referendums is that ultimately the voters get what they vote for. A majority for separation means separation. Yet there are exceptions to this rule. On April 8th, 1933, Western Australia voted in favour of seceding from the Australian Commonwealth, though it remains together to this day. What allowed the democratically expressed will of the people to be ignored? And what did it mean for Australia and its relationship with the British Empire?

Western Australia’s independent spirit appeared the moment it gained the right of self-government. This was in 1890, a year after talk of federalisation began. Not wishing to give up its newly acquired sovereignty, Western Australia did not attend the 1891 constitutional convention (although New Zealand did) and only sporadically and half-heartedly attended later conventions.

The secessionist movement would always claim that Western Australia was cajoled into federating and in some sense this is true. It was a gold rush that tipped the balance. Settlers flocked in from the east, bringing with them pro-federal opinions. When they heard that the Western Australian government was against federation, they started their own separatist movements. Thus Western Australia had a choice: refuse to federate and potentially see its gold-rich lands break away, or federate and maintain its territorial integrity. They opted for federation. But it did not take long before Western Australians began to regret their decision.

Before the end of 1902, the Australian parliament heard the first calls for secession. By 1919, the Sunday Times (one of Western Australia’s leading newspapers) had taken an openly secessionist stance and public demonstrations were held. The movement inspired rousing political rhetoric, poems and songs. It even received support from the governments of Tasmania and South Australia, which threatened their own referendums. And when the Western Australian electorate went to the polls, they voted 68 per cent in favour of secession.

And yet secession never came. In just a few years the secessionists’ faith in the British Empire was shattered and their movement had crumbled.

History Today for more