by SAMIN AMIN

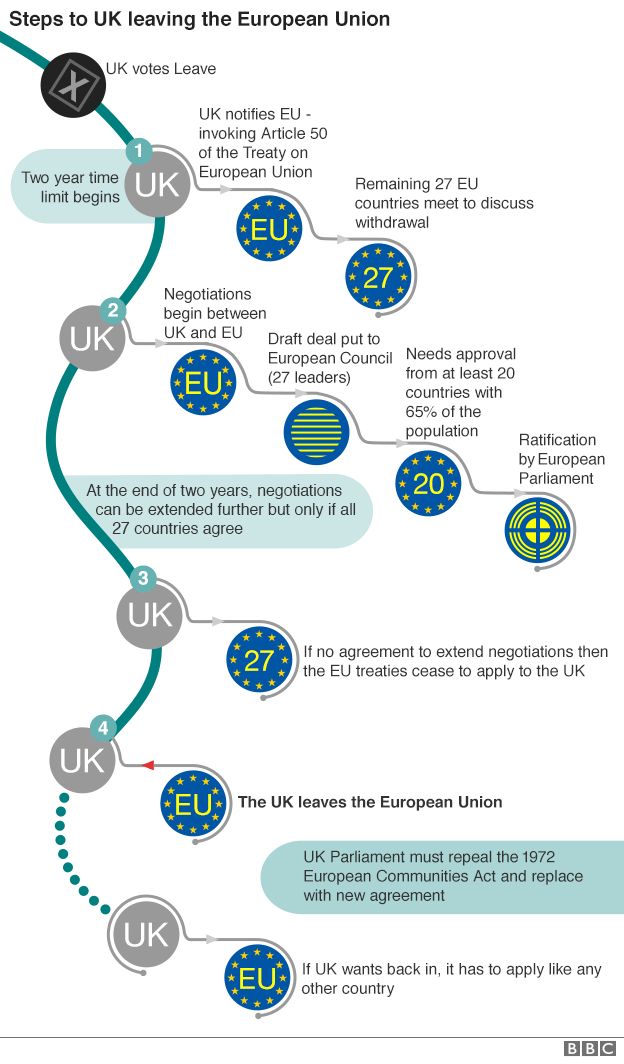

The process to take the UK out of the European Union starts with invoking Article 50 and will take at least two years from that point EXPLANATORY CHART/BBC

The process to take the UK out of the European Union starts with invoking Article 50 and will take at least two years from that point EXPLANATORY CHART/BBC

The defense of national sovereignty, like its critique, leads to serious misunderstandings once one detaches it from the social class content of the strategy in which it is embedded. The leading social bloc in capitalist societies always conceives sovereignty as a necessary instrument for the promotion of its own interests based on both capitalist exploitation of labor and the consolidation of its international positions.

Today, in the globalized neoliberal system (which I prefer to call ordo-liberal, borrowing this excellent term from Bruno Odent) dominated by financialized monopolies of the imperialist triad (the United States, Europe, Japan), the political authorities in charge of the management of the system for the exclusive benefit of the monopolies in question conceive national sovereignty as an instrument enabling them to improve their “competitive” positions in the global system. The economic and social means of the state (submission of labor to employer demands, organization of unemployment and job insecurity, segmentation of the labor market) and policy interventions (including military interventions) are associated and combined in the pursuit of one sole objective: maximizing the volume of rent captured by their “national” monopolies.

The ordo-liberal ideological discourse claims to establish an order based solely on the generalized market, where mechanisms are supposed to be self-regulatory and productive of the social optimum (which is obviously false), provided that competition is free and transparent (what it never is and cannot be in the era of monopolies), as it claims that the state has no role to play beyond guaranteeing that the competition in question functions (which is contrary to facts: it requires the state’s active intervention in its favor; ordo-liberalism is a state policy). This narrative — expression of the ideology of the “liberal virus” — prevents all understanding of the actual functioning of the system as well as the functions that the state and national sovereignty fulfill in it. The United States sets an example of decided and continuous practical implementation of sovereignty understood in this “bourgeois” meaning, that is to say today in the service of the capital of financialized monopolies. The “national” right allows the United States to enjoy its affirmed and reconfirmed supremacy over “international law.” It was the same in the imperialist countries of Europe of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Did things change with the construction of the European Union? European discourse claims and legitimates submission of national sovereignty to “European law,” expressed through the decisions of Brussels and the European Central Bank, under the Maastricht and Lisbon treaties. The freedom of choice of voters is itself limited by the clear supranational requirements of ordo-liberalism. As Mrs. Merkel said: “This choice must be compatible with market requirements”; beyond them it loses its legitimacy. However, in counterpoint to this discourse, Germany in practice affirms, in policies that are implemented, the exercise of its national sovereignty and seeks to submit its European partners to respecting its demands. Germany has used European ordo-liberalism to establish its hegemony, particularly in the eurozone. Great Britain — by its Brexit choice — has in turn affirmed its decision to pursue the advantages of exercising its national sovereignty.

We can comprehend then that “nationalist discourse” and its endless eulogy of the virtues of national sovereignty, understood in this way (bourgeois-capitalist sovereignty) without mentioning the class content of the interests that it serves, has always been subject to reservations, to put it mildly, from currents of the left in the broad sense, that is to say, all those who have the desire to defend the interests of the working classes. However, let us be wary of reducing the defense of national sovereignty to the terms of “bourgeois nationalism” alone. This defense is as necessary to serve other social interests as those of the ruling capitalist bloc. It will be closely associated with the deployment of capitalist exit strategies and commitment to the long road to socialism. It is a prerequisite of possible progress in this direction. The reason is that the effective reconsideration of global (and European) ordo-liberalism will never be anything but the product of uneven advances from one country to another, from one moment to another. The global system (and the European subsystem) has never been transformed “from above,” by means of collective decisions of the “international (or “European”) community.” The developments of these systems have never been other than the product of changes imposed within the states that compose them and what results from those changes concerning the evolution of power relations between them. The framework defined by the (“nation”) state remains the one in which decisive struggles that transform the world unfold.

The peoples of the peripheries of the global system, polarized by nature, have a long experience of this positive nationalism, that is to say anti-imperialist (expressing the refusal of the imposed world order) and potentially anti-capitalist. I say only potentially because this nationalism may also be carrying the illusion of building a national capitalism managing to “catch up” with the national constructions of the dominant centers. The nationalism of the peoples of the peripheries is progressive only on this condition: that it be anti-imperialist, breaking with global ordo-liberalism. In counterpoint, a “nationalism” (while only apparent) that fits in with globalised ordo-liberalism, and therefore does not question the subordinate positions of the concerned nation in the system, becomes the instrument of the local dominant classes keen to participate in the exploitation of their people and possibly of weaker peripheral partners towards which it acts as a “sub-imperialism.”

Today, advances — audacious or limited — allowing us to exit ordo-liberalism are necessary and possible in all parts of the world, North and South. The crisis of capitalism created a breeding ground for the maturation of revolutionary conjunctures. I express this objective, necessary, and possible imperative in a short sentence: “Exit the crisis of capitalism or exit capitalism in crisis?” (the title of one of my recent books). Exiting the crisis is not our problem, it is that of the capitalist rulers. Whether they succeed (and in my opinion they are not engaged in the paths that would enable it) or not is not our problem. What have we to gain by partnering with our adversaries to revive broken-down ordo-liberalism? This crisis created opportunities for consistent advances, more or less bold, provided that the fighting movements adopt the strategies that aim at them. The affirmation of national sovereignty then becomes obligatory to enable those advances that are necessarily uneven from one country to another but are always in conflict with the logic of ordo-liberalism. The sovereign national project that is popular, social, and democratic proposed in this paper is designed with this in mind. The concept of sovereignty implemented here is not that of bourgeois-capitalist sovereignty; it differs from it and for this reason must be qualified as popular sovereignty.

Monthly Review Zine for more