by GREG O’BRIEN

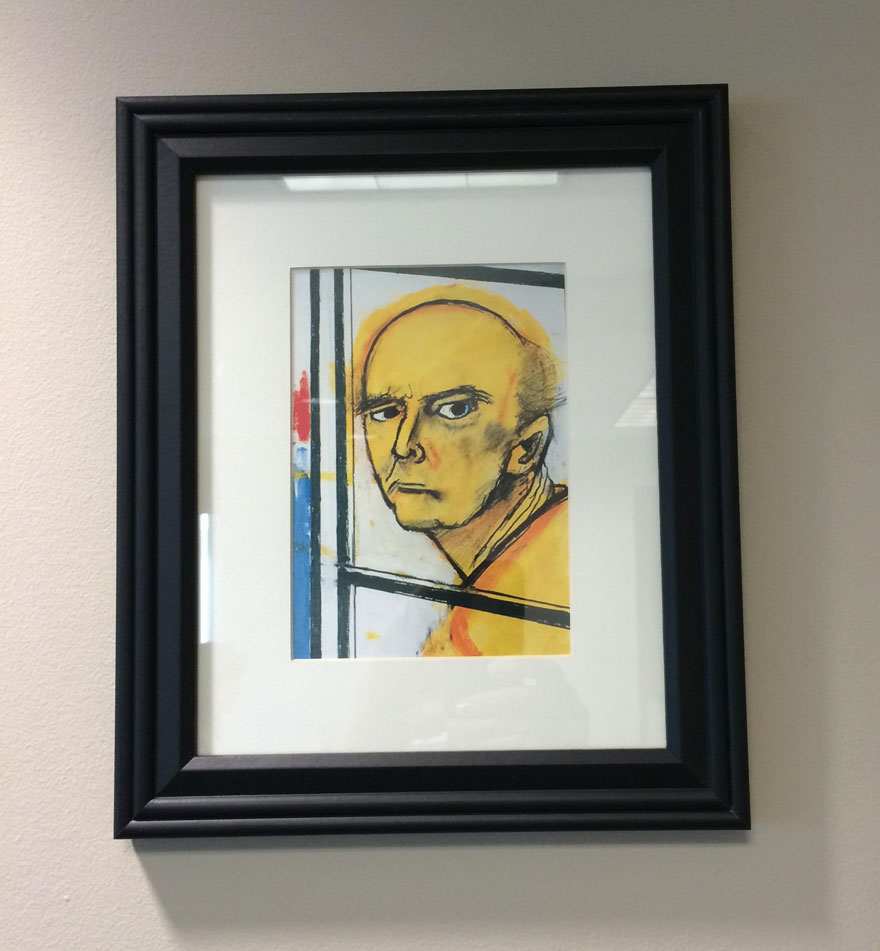

William Utermohlen, U.K.-based artist was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in 1995. The picture on the left was painted by him in 1996 and on the right in 2000. PHOTOS/Bored Panda

I was up again at 4 a.m. the other night, one of five nocturnal ramblings in the early morning, the new me. No sleep. Picking my way in the dark, familiar territory of a home on Cape Cod where I have lived with my family for 34 years.

I fumbled into the bathroom as I felt the numbness creep up the back of my neck like a penetrating fog, slowly inching to the front of my mind. It was as if a light in my brain had been shut off. I was overcome by the darkness of not knowing where I was and who I was. So I reached for my cellphone that substitutes as a flashlight, and called the house. My wife, deep asleep in our bed just 20 feet away, rose like Lazarus from the grave to grab the phone in angst, fearing a car crash with one of the kids or the death of an extended family member.

It was me, just me. I was lost in the bathroom.

was diagnosed in 2009 with early-onset Alzheimer’s, after Alzheimer’s stole my maternal grandfather and my mother, and several years before my paternal uncle died of Alzheimer’s. Clinical tests, MRIs and a brain scan confirmed my diagnosis. I also carry the Alzheimer’s marker gene APOE4. Two traumatic head injuries “unmasked” a disease in the making, my doctors tell me.

Today, 60 percent of my short-term memory can be gone in 30 seconds. I often don’t recognize friends, including, on two occasions, my wife. I get lost in familiar places, fly into inexorable rages, put my keys and cellphone in the refrigerator, my laptop in the microwave, and wash business cards in the dishwasher simply because they are dirty.

And at times, I see things that aren’t there. The most disturbing symptoms in my private darkness are the visual misperceptions, the hallucinations—those crawling, spider-and-insect like creatures that crawl along the ceiling regularly at different times of day, sometimes in a platoon, turning at 90 degree angles, then inching a third of the way down the wall before floating toward me. I brush them away, almost in amusement, knowing now that they are not real, yet fearful of the cognitive decline. On a recent morning, I saw a bird in my bedroom circling above me in ever-tighter orbits, before it precipitously dove to the bed in a suicide mission. I screamed. But it was my imagination.

Years ago as a journalist, I thought I was Clark Kent, Superman, an award-winning reporter who feared nothing. But today, I feel more like a baffled Jimmy Olsen. And on days of muddle, more like a codfish landed on the dock. A fish rots from the head down.

I never know who’s going to show up. Will I be on or off? I was off the other night, yet another reminder of the denouement of this plot. Stephen King couldn’t have written a better thriller.

When I sat down to write my own story, in my book, On Pluto: Inside the Mind of Alzheimer’s, my purpose was to offer a blueprint of strategies, faith, and humor, a day-to-day focus on living with Alzheimer’s, not dying with it—a hope that all is not lost when it appears to be. I was with my mother in the nursing home when she passed away, and told her moments before she died, “Mom, we’re riding this one out together.” She had always taught me to confront the demons in life.

Nautilus for more