by JOHN FEFFER

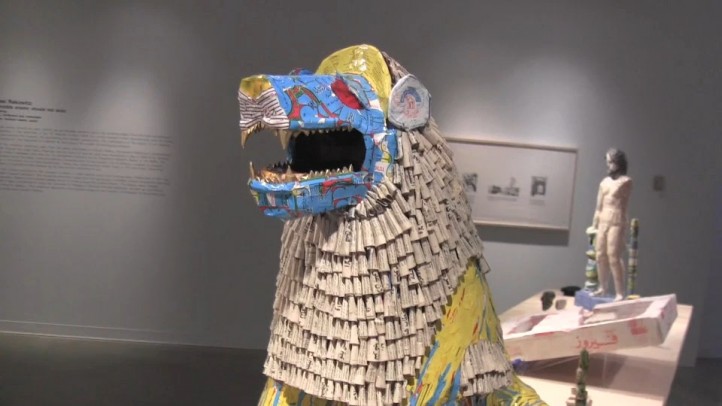

Tell Harmal lion by Michael Rakowitz

Tell Harmal lion by Michael Rakowitz

Here is one artist’s attempt to reconstruct what the Iraq War destroyed

In the initial aftermath of the U.S. invasion of Iraq, looters swept through the National Museum in Baghdad and carted off 15,000 items of incalculable value. Some of these items were destroyed in the attempt to spirit them away. Some disappeared into the vortex of the underground art market. Only half of the items were eventually recovered.

In February 2015, after a dozen years in limbo, Iraq’s National Museum reopened. But it was a bittersweet reopening, and not only because of the thousands of missing treasures. That February, Islamic State (ISIS or IS) militants recorded themselves smashing priceless objects in the central museum in Mosul, a city in northern Iraq that IS had occupied since June 2014. U.S. troops had largely left the country, and Washington had declared the war over. But the destruction of Iraq—its heritage and its people—was still ongoing.

Michael Rakowitz is involved in a massive reclamation project. Since 2007, in a project called The invisible enemy should not exist, the Iraqi American artist has been recreating the lost treasures of Iraq. He and his studio assistants locate the description of the objects, along with their dimensions and sometimes a photograph, on the Interpol or Oriental Institute of Chicago websites, which have been set up to deter antiquity dealers from buying looted artifacts. Then they set to work.

“To date, we’ve reconstructed 500 of the 8,000 objects,” Rakowitz says. “It’s potentially a project that will outlive me and my studio.” In addition to the objects looted from the National Museum, they’ve begun to reconstruct pieces that IS has destroyed in Mosul, Nineva, and Nimrod.

Rakowitz recently gave me a tour of an exhibit of these reconstructed objects at the George Mason University School of Art, which was part of the Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here Project. The largest piece on display is a brightly colored lion that stands about three feet tall.

“The Tell Harmal lion was destroyed,” Rakowitz says of the lion that once stood in the main temple of the Babylonian city of Shaduppum (today known as Tell Harmal) over 3,500 years ago. “Looters tried to take the head off the lion, and not knowing how fragile the terra cotta was, the entire head shattered beyond repair. We don’t just reconstruct the head but the entire lion: to give the viewer a sense of what that lion’s ghost might look like.”

The lion destroyed in Baghdad in 2003 was various shades of grey and white. But the reconstructed lion has a yellow torso and blue jaws. The difference in coloring is a function of the materials used for the reconstruction. “The artifacts are reconstructed out of the packaging of Middle Eastern foodstuffs and the Arabic-English newspapers available in the US where there are Arab communities,” Rakowitz explains.

Foreign Policy in Focus for more