by ROBERT MINTO

IMAGE/Amazon

IMAGE/Amazon

by Sarah Bakewell

Other Press: 2016

The story of the philosophical movement known as existentialism is full of big personalities, punctuated by world wars, and riven by personal feuds conducted in public. It gave us a host of icons: Sartre, walleyed and piping; Camus, moodily popping the collar of his leather jacket; Beauvoir, scribbling in hotel rooms. Whatever else you can say about it, existentialism was dramatic. Of course, there is a lot else you can say about it. For instance, what was it?

Partisans will gesture to the slogan, “existence precedes essence,” a sonorous bit of obscurity that basically means humans are both limited by circumstance and unlimited in self-interpretation. But that’s hardly a remarkable thesis in the Western philosophical tradition, which has always been obsessed by the problems of free will and determinism. In fact, the most salient characteristics of existentialism were not its ideas but its personalities, thinkers who made the ideas exciting, sexy, dangerous. Existentialism is the ultra-sophomore ideology, unmistakable as a style even when you have no idea what it means.

It was certainly my sophomore ideology. Reading Sarah Bakewell’s At the Existentialist Café, I am reminded of going to college and becoming a philosophy major: staying up all night arguing about metaphysics over bottles of wine, affecting a pipe, relishing the louche, outré, and counter-cultural, and considering myself philosophically serious and superior for these choices. I, and those of my present-day students who are living the same experiment, have our archetype in the café lives of the existentialists. Bakewell writes that,

even when the existentialists reached too far, wrote too much, revised too little, made grandiose claims, or otherwise disgraced themselves, it must be said that they remained in touch with the density of life, and that they asked the important questions. Give me that any day, and keep the tasteful miniature for the mantelpiece.

Obviously the proper genre for studying such a philosophical movement is biography. And so Bakewell decided: “I want to explore the story of existentialism…in a way that combines the philosophical and biographical.”

This, her fourth book, applies a method of intellectual history she first tried out in How to Live (2010), a book about Montaigne. The method is not just popularization—though its effect is certainly to popularize its subjects—but something more like necromancy. Bakewell puts ideas back in the mouths that uttered them, then describes those mouths, their cracked or glistening lips, and conjures the events that moved them to speak. For Bakewell, theories and the books that convey them are acts in the drama of interesting lives. No matter how abstruse her subject, it lives.

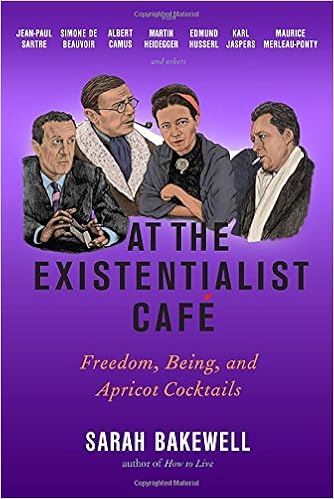

Across the top of this book’s dust cover, some of the names of the philosophers she discusses are listed like the names of actors on a movie poster. Indeed, Bakewell’s models seem to be biopics and documentaries rather than other books. Most chapters begin with a scene rather than a thesis. Each chapter title includes a sub-heading like this for Chapter 5: “In which Jean-Paul Sartre describes a tree, Simone de Beauvoir brings ideas to life, and we meet Maurice Merleau-Ponty and the bourgeoisie.” As a consequence of these and other stratagems, Bakewell’s book is lively and odd enough to hold the attention of readers who don’t have the stamina for more standard types of intellectual history.

Open Letters Monthly for more