by NYLA ALI KHAN

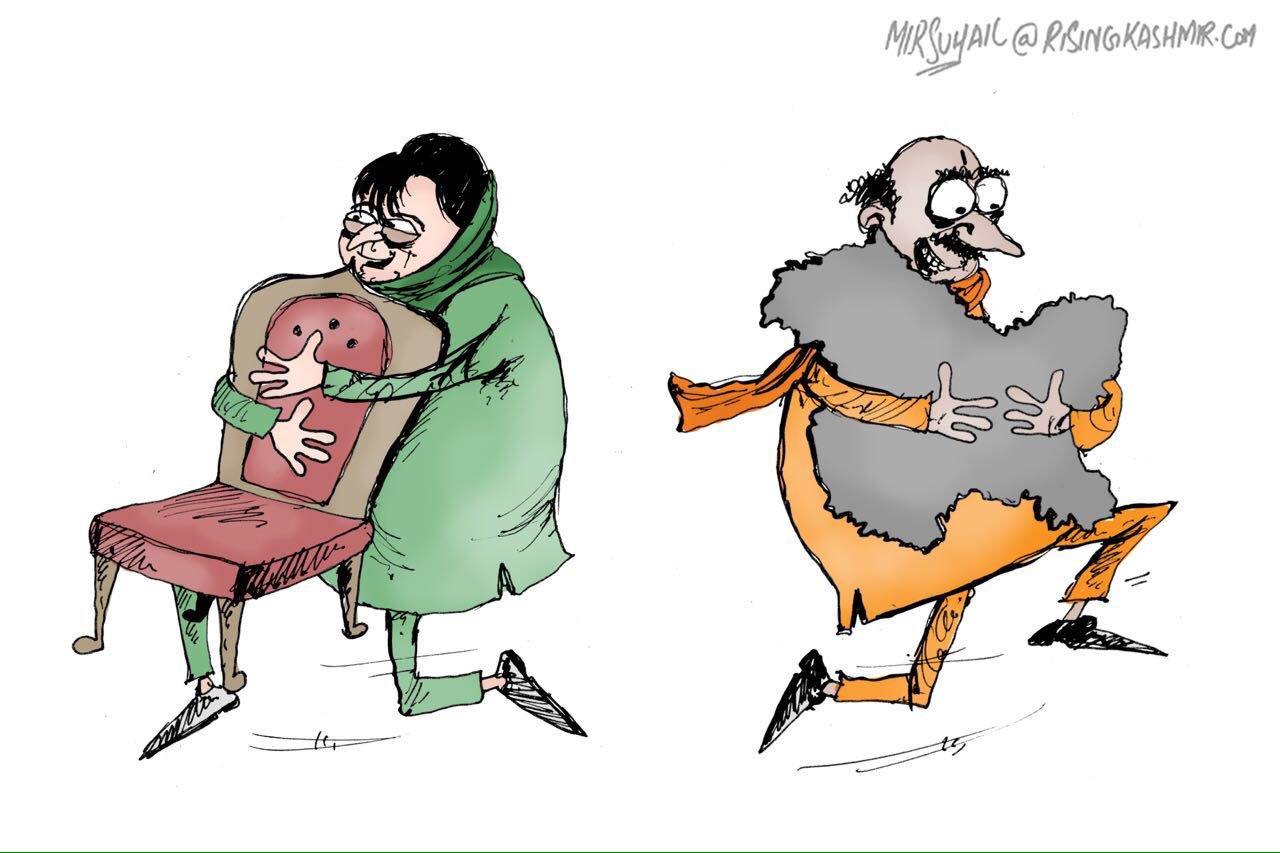

CARTOON/Mir Suhail/Twitter

CARTOON/Mir Suhail/Twitter

The turbulence and turmoil that has haunted Kashmir for the past twenty-three years holds all of us, as a people, accountable for the degeneration of our politics and society. While it is important for us to condemn, question, and seek redressal for the human rights violations in Kashmir, it is also important for us to construct a politics that would enable the rebuilding of our pluralistic polity and society. The more we allow the depoliticization of our society, the more subservient we become to forces that do not pay heed to Kashmir’s best interests. Any organization that protects and promotes vested interests while marginalizing the general populace is by no means democratic. The alternative is not the dismantling of our political structures and institutions of governance but the creation of a viable political structure, one in which “a popular politics of mass mobilization is merged with institutional politics of governance promoting demilitarization and democracy”. My understanding of pluralism is that we set our house in order by the creation of Responsible Government. . . . The first condition to achieve Responsible Government is the participation of all those people, not just the Muslims alone nor the Hindus and the Sikhs alone, nor the untouchables or Buddhists alone, but all those who live in this state. The demand for Responsible government should extend not just to the Muslims of Jammu & Kashmir, but all state subjects. A representative government would enable the devolution of administrative responsibilities to districts and villages. Pluralism in J & K emphasized the necessity of abolishing exploitative landlordism without compensation, enfranchising tillers by granting them the lands they worked on, and establishing cooperatives. It also addressed issues of gender, and instituting educational and social schemes for marginalized sections of society. A pluralistic government sought to create a more democratic and responsible form of government.

Women citizens were accorded equal rights with men in all fields of national life: economic, cultural, political and in the state services. These rights would be realized by affording women the right to work in every employment upon equal terms and for equal wages with men. Women would be ensured rest, social insurance and education equally with men. The law would give special protection to the interests of mother and child. This metamorphosis of the agrarian economy had groundbreaking political consequences.

The purportedly autonomous status of J & K under Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah’s government provoked the ire of ultra right-wing nationalist parties, which sought the unequivocal integration of the state into the Indian union. The unitary concept of nationalism that such organizations subscribed to challenged the basic principle that the nation was founded on: democracy. In this nationalist project, one of the forms that the nullification of past and present histories takes is the subjection of religious minorities to a centralized and authoritarian state. The unequivocal aim of the supporters of the integration of J & K into the Indian union was to expunge the political autonomy endowed on the State by India’s constitutional provisions. According to the unitary discourse of sovereignty disseminated by ultra right-wing nationalists, J & K wasn’t entitled to the signifiers of statehood.

In October 1949, the Constituent Assembly of India reinforced the stipulation that New Delhi’s jurisdiction in the state would remain limited to the categories of defense, foreign affairs, and communications, which had been underlined in the Instrument of Accession. Subsequent to India acquiring the status of a republic in 1950, this constitutional provision enabled the incorporation of Article 370 into the Indian constitution, which ratified the autonomous status of J & K within the Indian Union. Article 370 stipulates that New Delhi can legislate on the subjects of defense, foreign affairs, and communications only in just and equitable consultation with the Government of Jammu and Kashmir State, and can intervene on other subjects only with the consent of the Jammu and Kashmir Assembly.

The subsequent negotiations in June and July 1952 between a delegation of the J & K government led by Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah and Mirza Afzal Beg, and a delegation of the Indian government led by Jawaharlal Nehru resulted in the Delhi Agreement, which maintained the status quo on the autonomous status of J & K. In his public speech made on 11 August, Abdullah declared that his aim had been to preserve “maximum autonomy for the local organs of state power, while discharging obligations as a unit of the [Indian] Union” (quoted in Soz 1995: 128). At the talks held between the representatives of the state government and the Indian government, the Kashmiri delegation relented on just one issue: it conceded the extension of the Indian supreme court’s arbitrating jurisdiction to the state in case of disputes between the federal government and the state government or between J & K and another state of the Indian Union. But the Kashmiri delegation shrewdly disallowed an extension of the Indian Supreme Court’s purview to the state as the ultimate arbitrator in all civil and criminal cases before J & K courts. The delegation was also careful to prevent the financial and fiscal integration of the state with the Indian Union. The representatives of the J & K government ruled out any modifications to their land reform program, which had dispossessed the feudal class without any right to claim compensation. It was also agreed that as opposed to the other units in the Union, the residual powers of legislation would be vested in the state assembly instead of in the centre. The political logic of autonomy was necessitated by the need to bring about socioeconomic transformations, and so needs to be retained in its original form.

The autonomy of the state within the Indian Union had been proclaimed in 1950 by a constitutional order formally issued in the name of the president of India. But in 1954, the former order was rescinded by the proclamation of another dictum that legalized the right of the central government to legislate in the state on various issues. First off, the state was financially and fiscally integrated into the Indian Union; the Indian Supreme Court was given the authority to be the undisputed arbiter in J & K; the fundamental rights that the Indian constitution guaranteed to its citizens were to apply to the populace of J & K as well, but with a stipulation: those civil liberties were discretionary and could be revoked in the interest of national security. In effect, the authorities had carte blanche for the operation of unaccountable police brutality in the state.

New Delhi asserts, time and again, that a revitalized Indian federalism will accommodate Kashmiri demands for an autonomous existence. But, historically, federalism hasn’t always adequately redressed the grievances of disaffected ethnic minorities. Here, I concur with Robert G. Wirsing’s observation that, “while autonomy seems to imply less self-rule than does the term confederalism, for instance, it is generally understood to imply greater self-rule than federalism, which as in the American case, need not cater to ethnic group minorities at all” (2003: 199).

In 1956 the Constituent Assembly validated a draft constitution for the state, built on the premise that the state of J & K was and, indubitably, would remain an integral part of the Union of India. This unambiguous premise assigned the political inclinations of the people of Kashmir to an obscure position. In fact Nehru unabashedly declared that the legality of the accession of Kashmir to India was now a moot issue. This undemocratic approach did not go unchallenged, and Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah wrote protest letters from prison to his former ally Nehru, and to his former trusted political comrade G.M. Sadiq, the pro-communist speaker of the Assembly. Despite his incarceration, Abdullah’s larger-than-life political status and clout, reified by his die-hard supporters, kept alive the issues of self-determination and special status. When the draft constitution was placed before the house, Mirza Afzal Beg moved a motion of adjournment for exactly two weeks, in order to enable Abdullah to be present. The Assembly was presided over by Sadiq who ruled the motion out of order. Subsequently, Beg and his followers protested and boycotted the proceedings (Dasgupta 2002: 97). The large-scale repressive measures deployed by the government of India paved the way for it to firmly entrench the state’s new constitution on 26 January 1957. This development was followed by a resolution of the UN Security Council, which reiterated that the final status of J & K would be settled in accordance with the wishes of the people of the state as expressed in a democratic plebiscite. In effect, the convening of a Constituent Assembly as recommended by the general council of the All Jammu & Kashmir NC would not determine, in any way, shape or form, the political future of the state. The course of the political destiny of J & K would be charted by the voice of its people raised at a democratic forum under the auspices of the UN (ibid.: 408). The resolution affirmed that the Kashmir issue was still pending final settlement and, despite claims to the contrary by Nehru’s Congress government, was under consideration by the Security Council. The reiteration of earlier UN resolutions regarding the Kashmir issue made explicit the disputed status of the state. However, the UN was unable to retard or prevent certain political developments in J & K.

Soon after validating the new constitution, the Constituent Assembly dissolved itself and sought the organization of mid-term elections in order to constitute a new Legislative Assembly. At the time, the jurisdiction of the Election Commission of India did not extend to J & K. Although the election that was held in June of 1957 had a semblance of political equity, Abdullah’s bête noir and a politician whose notoriety was by then unsurpassed, Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad, won his seat without any contest. Bose (2003: 75) makes some interesting observations about the mockery of the electoral process in the state that year, in which Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad’s National Conference won 66 seats. Electoral contests of dubious authenticity occurred for only 28 seats. In brazen disregard of democratic processes, of 43 Kashmir Valley seats, 35 were won by official NC candidates without even the semblance of a contest; 30 NC candidates, including Bakshi, won overwhelming victories without an iota of opposition; and another 10 NC candidates were elected after the nomination papers filed by opposing candidates were invalidated. Not surprisingly, the official responsible for vetting the nomination papers was an unscrupulous Bakshi adherent, Abdul Khaleq. In the Jammu region, there was a contest of sorts for 20 of the 30 seats – the NC won 14 seats, the Praja Parishad bagged 5, and a party representing ‘low-caste’ Hindus secured 1 seat.

The organization of a well-manipulated electoral process had enabled New Delhi to ensure the victory of the stooge faction that it patronized. Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad, who had been elected as the leader of the NC legislative party without dispute, was reinstalled as prime minister. Bakshi and his cohorts were firmly entrenched not just in the Legislative Assembly, but in the Legislative Council as well. The monopolization of both houses of the Assembly by a political faction sponsored by New Delhi legitimized a full-scale intervention of the central government, allowing the incorporation of non-Kashmiri officials in important administrative positions and the subsequent marginalization of the well-educated segments of Kashmiri Muslims. The Pandit population of the Valley, which was a small minority, enjoyed privileges in the political, civil and economic structures of which the Muslim majority was deprived.

During these fateful years in the history of Kashmir, a wide fissure was created within the ruling clique when Bakshi, in his signature style, did not incorporate any members of the Communist faction headed by G.M. Sadiq into the cabinet that he formed subsequent to the 1957 elections. Bakshi’s inability or unwillingness to appease this faction motivated Sadiq to create a separate organization, the Democratic National Conference, with the rebel Communist group of fifteen legislators. New Delhi recognized the threat that the rebelliousness of this faction could cause not just to the constructed political stability within the state, but also to India’s relationship with China which was already on the decline. The Chinese government had ratified an agreement with the military regime in Pakistan which specified that after the Kashmir dispute between the governments of Pakistan and India had been settled, the pre-eminent authority concerned would initiate negotiations with the government of the People’s Republic of China in order to implement a boundary treaty to replace the present agreement. It reinforced its alliance with Pakistan’s military regime by underlining that if that supreme and indisputable authority was Pakistan, then the provisions of the present agreement would be reinforced (Dasgupta 1968: 389–91). The prospect of the Pakistan – China alliance being bolstered spurred New Delhi to bring about a rapprochement between Bakshi’s and Sadiq’s warring factions in 1960. Sadiq and his cohort were reincorporated into the cabinet. A couple of years after this reconciliation, in 1962, Assembly elections were held in the state, and Bakshi and his cabinet colleagues Sadiq, Mir Qasim and Khwaja Shamsuddin won their Assembly seats without even a peep of opposition (Bose 2003: 78). That year elections were held to 60 seats in the entire state, out of which the Bakshi-led NC suspiciously won 55; the Praja Parishad won 3 (telephonic conversation with Sheikh Nazir Ahmad, late General Secretary of the NC, 8 January 2009).

Bakshi’s arrogance, and rampant deployment of corrupt and illegal methods and malpractices in political processes, soon caused him to be an embarrassment for the “democratic” government of the Republic of India, and his mentors in New Delhi had to ask him to step down from the position of prime minister of the state; Bakshi resigned in November 1963. The political bigwigs in New Delhi were concerned that another unopposed election in the state would tarnish India’s reputation as the largest democratic republic. So Nehru’s unsolicited advice to Bakshi was that he would gain more credibility and the elections could boast of an air of fairness if he lost a few seats to ‘bona fide opponents’. Bakshi’s political indebtedness to Nehru and his clique prevented him from discounting Nehru’s advice, and he was replaced as prime minister by a hitherto unknown political entity, Khwaja Shamsuddin. Although the new government was headed by Shamsuddin, Bakshi’s political clout buoyed by his practices of his goons remained a formidable presence. Consequently, his political rival who enjoyed the patronage of the same political forces that had enabled Bakshi’s ascendancy was not accommodated in the new government (Puri 1995: 45–49).

In December 1964, the Union government declared that two highly federalist statutes of the Indian Constitution would be enacted in J & K: Articles 356 and 357. These draconian Articles enable the centre to autocratically dismiss democratically elected governments if it perceives a dismantling of the law and order machinery. A constitutional order implementing these statutes was decreed by New Delhi. In 1956, the Union government fortifies its autocratic powers in J & K by getting several corrosive amendments passes in the state Assembly: the Sadr-i-Riyasat or titular head of the state was replaced by governor, a political nominee appointed by the centre; the title of head of government was changed from prime minister to chief minister, which was the regular title of heads of government within the Indian Union; state representatives to the lower house (Lok Sabha) of India’s Parliament would no longer be nominated by the state legislature but would be elected. These amendments were highly centrist and were designed to corrode the autonomy of J & K provided by Article 370.

A dozen or more summit conferences have been held between the government heads of India and Pakistan toward the resolution of the Kashmir problem, from Nehru-Liaquat to Vajpayee-Musharaf meetings, laced in between with Soviet-American interventions, and a series of meetings between foreign ministers Swaran Singh and Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, but nothing worth reporting was ever achieved, primarily because the people of J & K were never made a part of these parleys. The only silver lining to this huge cloud of failures was the signing of the 1952 Delhi Agreement, signed between two elected prime ministers, Nehru and Abdullah. As a viable beginning to a lasting resolution, it is high time that 1952 Delhi Agreement is returned to in letter and spirit. The political logic of autonomy was necessitated by the need to bring about socioeconomic transformations, and so needs to be retained in its original form. Until then, opening up of trade across the LOC, which still has a lot of loopholes, and enabling limited travel would be cosmetic confidence building measures. Until the restoration of autonomy as a beginning, even the people oriented approach adopted by the then Vajpayee-led NDA government and Musharraf’s four-point formula would remain merely notional.

Bibliography

Ahmad, Sheikh Nazir, Late General Secretary of the National Conference (NC), April 2008.

Bose, Sumantra, Kashmir: Roots of Conflict, Paths to Peace, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2003.

Dasgupta, Jyoti Bhusan, Jammu and Kashmir, The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1968.

Puri, Balraj, Kashmir: Towards Insurgency, New Delhi: Orient Longman, 1995.

Soz, Saifuddin, Why Autonomy to Kashmir?, New Delhi: India Centre of Asian Studies, 1995.

Wirsing, Robert, India, Pakistan, and the Kashmir Dispute, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1994.

(Nyla Ali Khan is a faculty member at the University of Oklahoma, and member of Scholars Strategy Network. She is the author of Fiction of Nationality in an Era of Transnationalism, Islam, Women, and Violence in Kashmir, The Life of a Kashmiri Woman, and the editor of The Parchment of Kashmir. She is editor of the Oxford Islamic Studies’ special issue on Jammu and Kashmir. She can be reached at nylakhan@aol.com)