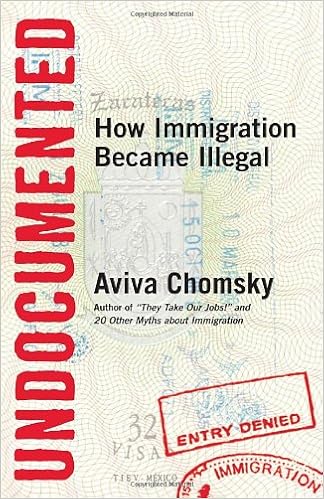

by AVIVA CHOMSKY

IMAGE/Amazon

IMAGE/Amazon

In our post-modern (or post-post-modern?) age, we are supposedly transcending the material certainties of the past. The virtual world of the Internet is replacing the “real,” material world, as theory asks us to question the very notion of reality. Yet that virtual world turns out to rely heavily on some distinctly old systems and realities, including the physical labor of those who produce, care for, and provide the goods and services for the post-industrial information economy.

As it happens, this increasingly invisible, underground economy of muscles and sweat, blood and effort intersects in the most intimate ways with those who enjoy the benefits of the virtual world. Of course, our connection to that virtual world comes through physical devices, and each of them follows a commodity chain that begins with the mining of rare earth elements and ends at a toxic disposal or recycling site, usually somewhere in the Third World.

Closer to home, too, the incontrovertible realities of our physical lives depend on labor — often that of undocumented immigrants — invisible but far from virtual, that makes apparently endless mundane daily routines possible.

Even the most ethereal of post-modern cosmopolitans, for instance, eat food. In twenty-first-century America, as anthropologist Steve Striffler has pointed out, “to find a meal that has not at some point passed through the hands of Mexican immigrants is a difficult task.” Medical anthropologist Seth Holmes adds, “It is likely that the last hands to hold the blueberries, strawberries, peaches, asparagus, or lettuce before you pick them up in your local grocery store belong to Latin American migrant laborers.”

The same is true of the newspaper. The invisible links between two mutually incomprehensible worlds were revealed to many in the Boston area at the end of December when the Boston Globe, the city’s major newspaper, made what its executives apparently believed would be a minor change. They contracted out its subscriber delivery service to a new company.

Isn’t newspaper delivery part of the old economy and so consigned to the dustbin of history by online news access? It turns out that a couple of hundred thousand people in the Boston area — and 56% of newspaper readers nationwide — still prefer to read their news in what some dismissively call the “dead tree format.” In addition, despite major ad shrinkage, much of the revenue that allows newspapers to offer online content still comes overwhelmingly from in-print ads.

The Globe presented the change as a clean, technical move, nothing more than a new contractor providing newspaper delivery for a lower cost. But like so many other invisible services that grease the wheels of daily life, that deceptively simple task is in fact provided thanks to grueling, exploited labor performed by some of society’s most marginalized workers, many of them immigrants and undocumented.

In this respect, newspaper delivery shares characteristics with other forms of labor that link the privileged with the exploited. This is especially true in Boston, recently named the most unequal city in the country. Some of the most dangerous, insecure, and unpleasant jobs with the lowest pay and a general lack of benefits provide key goods and services for citizens who undoubtedly believe that they never interact with immigrants or receive any benefits from them.

In fact, immigrant workers harvest, process, and prepare food; they provide home health care; they manicure hands and lawns. In other words, the system connects some of the most intimate aspects of our daily lives with workers whose very existence is then erased or demonized in the public sphere. And all of this happens because these workers are regularly rendered silent and invisible.

Reporters Heroically Deliver the Paper

Tom Dispatch fro more