by DAVID-NGENDO TSHIMBA

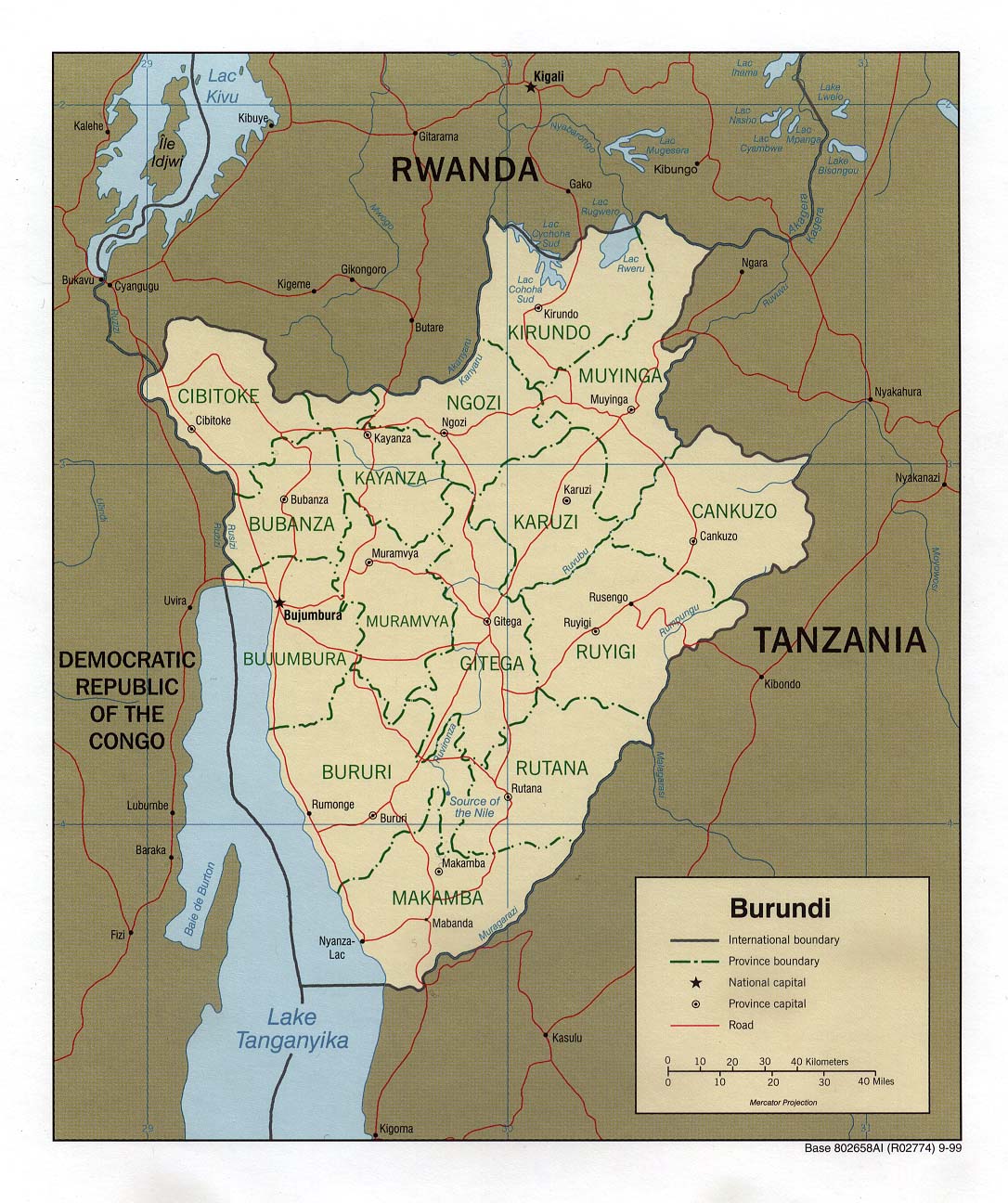

Map of Burundi MAP/Library, University of Texas

Map of Burundi MAP/Library, University of Texas

In the run-up to independence in 1962, Burundi held national elections in September 1961 contested between two rival groups of traditional princes (Ganwa): the Bezi, represented by the Union pour le Progrès National (UPRONA) party, and the Batare, represented by the Parti Démocrate Chrétien (PDC) party. The then popular and pro-independence king’s son, Prince Louis Rwagasore, whose UPRONA [Union for National Progress] had just won the elections in preparation for independence, became the de facto independence leader thanks to a triumphant victory gaining 58 of the 64 seats. The Belgian colonial administration, in a move to oppose UPRONA, had supported PDC [Christian Democrat Party]. Peter Uvin, a no less important scholarly voice in the political history of contemporary African Great Lakes region, noted that the multi-ethnic dimension of UPRONA was conspicuous in the outcomes of these elections: of its members elected, “25 were Tutsi, 22 Hutu, 7 Ganwa and 4 of mixed parentage.”

Barely a month after the electoral victory of UPRONA, Prince Rwagasore—of Ganwa descent, therefore neither Tutsi nor Hutu—was assassinated on 13 October 1961 by a Greek mercenary who, according to a historical reading by Burundian cleric Zacharie Bukuru, had been recruited by UPRONA’s political adversaries (members from the PDC) in collusion with some Belgian colonial officials.

By and large, the historic assassination of Prince Rwagasore remains colossal in the unfolding events of post-independence Burundi: it indeed represents the day on which doors were closed for Burundi’s post-colonial democratic dispensation. Soon after his death, sheer divisions among the pre-independence Burundian political elite grew even deeper, more so fuelled by the fear borne by the then prevailing manhunt against the Tutsi in Rwanda.

Political power, which had for so long remained in the hands of the royal family, was soon coveted by both Hutu and Tutsi intellectuals of the time. Burundi’s traditional monarch, Mwami (king) Mwambutsa—historically popular among both Hutu and Tutsi—resumed a governing role and called for legislative elections in May 1965, after the Hutu Premier he had appointed, Pierre Ngendandumwe, was assassinated three days into his office. The then king had tried to satisfy everyone by changing prime ministers (a Prince, a Hutu and a Tutsi premier) but all in vain. According to René Lemarchand, another no less influential scholarly voice in the study of contemporary African Great Lakes politics, Prime Minister Ngendandumwe’s assassin—a Rwandan refugee—was employed by the United Sates Embassy in Bujumbura just because the administration there suspected the Prime Minister of being a communist; suspicion was awakened because of some links he had opened with China.

This barbaric act of assassination of a Burundian Hutu premier by a Rwandan Tutsi refugee further nourished extremism of the Hutu against the Tutsi in Burundi. The subsequent legislative elections, which were organised three months later, took place in a tense atmosphere of ethnic connotation. Its outcomes were expectedly construed to be a victory of one ethnicity over the other. A big majority of elected members of the legislative assembly (MPs) consisted of the Hutu. Although with a huge Hutu majority in the legislature, the Tutsi politico-military elite was determined to deny power to the Hutu.

King Mwambutsa appointed Léopold Biha as Prime Minister much as the Hutu had won a majority in the legislative elections. Consequently, a small group of frustrated Hutu army officers and gendarmes staged on 19 October 1965 an attack on the royal palace and shot Prime Minister Biha (albeit not fatally) in the king’s compound, only to be stopped by Tutsi army officers led by Captain Michel Micombero.

This assassination plot—coupled with the prevailing conviction by Hutu mobs in the northern province of Muramvya who mistakenly believed the Tutsi had turned against the Mwami and hence attacked Tutsi civilians—precipitated in the country a bloody civil war. It became evident that the case of Rwanda then—whereby, in 1959, the Hutu, after having exiled the king and massacred the Tutsi, went on to declare independence of a Rwandan republic—had, on the one hand, appealed to the Hutu elite in Burundi and had become frightening to the Burundian Tutsi elite, on the other hand.

Pambazuka News for more