by ISTVAN JOZSA and GEERT LOVINK

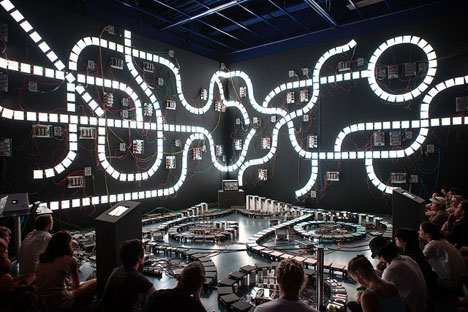

“…and then build it.” Pictured above: Your-Cosmos, an installation by Japan’s Miraikan National Museum of Emerging Science and Innovation and the Ars Electronica Futurelab, September 2013. PHOTOFlorian Voggeneder/Flickr

“…and then build it.” Pictured above: Your-Cosmos, an installation by Japan’s Miraikan National Museum of Emerging Science and Innovation and the Ars Electronica Futurelab, September 2013. PHOTOFlorian Voggeneder/Flickr

Reinventing our culture in the Internet age

Istvan Jozsa: Poems, stories, and novels have been written since ancient times; Boccaccio’s Decameron is over six hundred years old. There are narrative traditions that stretch over millennia. Today, well established genres are being deconstructed using worldwide communication “tools” such as blogs, chat, Skype and Facebook, with their likes and comments. These tools are replacing the telephone, the letter, the use of maps, the sharing of feelings, places suited to meeting in person, discussions, shopping in malls or markets.

I do not want to deny the possible advantages inherent to Facebook, as it is obvious to me that in some cases it is a useful communication platform. Facebook works for free and offers many opportunities. It is convenient if you want to create groups, read the latest news and follow ongoing events. It offers the chance to find people and get in touch with friends and acquaintances whom we haven’t seen for a while. These facilities may also take a negative turn when used to insult someone publicly with comments that would otherwise be “nobody’s business”. Most of the thoughts shared on Facebook are informal texts. But my question is: are new genres being born at the beginning of the third millennium, genres that never existed before?

Geert Lovink: The Internet as a mass phenomenon is relatively new. Historically speaking, it is only recently that large sectors of the population still had to figure out what the Internet was all about. This means we’re finally moving on from basic questions of the Internet’s materiality and ontology to a wider debate about its larger purpose. It is no longer enough to measure and discuss its impact. There is, at present, a rapidly closing window of opportunity to have a broad consultation about which Internet you want, and then build it. If you do not want to depend on monopoly services from elsewhere, and yet complain about a dependency on “foreign” cultures, it is time to act. You can’t have it both ways. This also applies to Central and Eastern Europe. You are an actor and no longer a victim. Either you get involved with building independent infrastructures or accept that you will be Facebook and Google subjects for decades to come, condemned to do little more than spread resentment about the loss of your “culture”. Media architectures have consequences. And once they are installed, they tend to withdraw into the background and become part of your invisible every day life routines. Once so embedded, it becomes very difficult to change such power structures.

Eurozine for more