by YOSHIMI YOSHIAKI

(translated and introduced by ETHAN MARK

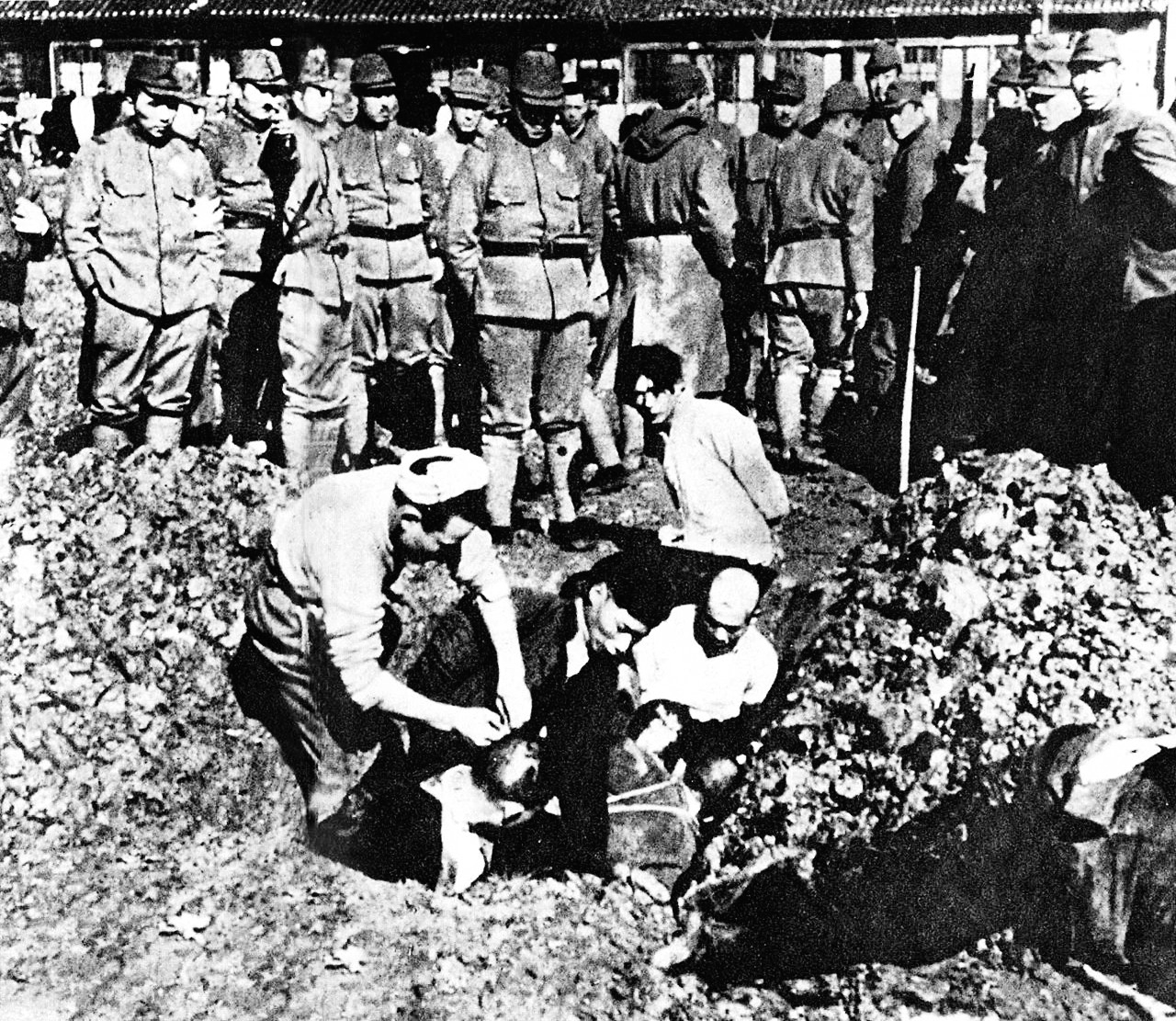

Chinese prisoners being buried alive by the Japanese forces during the Second Sino-Japanese War and World War II PHOTO/Wikipedia

Chinese prisoners being buried alive by the Japanese forces during the Second Sino-Japanese War and World War II PHOTO/Wikipedia

Grassroots Imperialism

When the Sino-Japanese War began on July 7th 1937, popular calls for “imperialism externally,” a desire previously well buried, suddenly came to the fore. Along with limits on freedom of expression and the manipulation of public opinion, a number of other factors began to have a determining influence on popular consciousness. There was a manner of thinking along the lines of a fait accompli: “Now that the war has started, we’d better win it.” There was a strong sense that Japan was winning the war. And by the end of 1937, Japan had dispatched some 770,000 troops, a reality that weighed heavily.

According to a national survey of thirty-eight municipalities conducted at the end of 1937 by the Cabinet Planning Board’s Industry Section, the attitude of people in farming, mountain, and fishing villages towards the war against China, summarized in terms of a single village, was divided between “the middle class and up,” who “want the war to be pursued … to the fullest (to the point that [hostilities] will not flare up again),” and “the middle class and below,” who “want it to be brought to as speedy an end as possible.”5

If we examine the calls for a speedy end to the war more closely—voices mostly from “the middle and below”—the following sorts of examples emerge with particular force.

a. “We hope that it ends quickly. (We hope that overseas development will be possible. There is only one person who does not want to leave the village and emigrate to Manchuria).”

b. “In order to extend Japan’s influence in northern China, we are planning to send out two or three of my boys.”

c. “To compensate for all the sacrifices the Imperial Army has made, [(North and Central China]) should be brought under the control of the Empire.”

d. “We hope that we’ll be able to secure considerable rights and interests.”

Each of these statements represented a hope for a swift end to the war that went hand in hand with a yearning for concrete profits or rights and interests, clearly demonstrating that a “grassroots imperialism” ideology had begun to surge among the people. The people of the town of Kawashima in Kagawa Prefecture were a representative example. Reflecting the complexity of popular attitudes, it was reported here that “if the war goes on for long it will be a problem—this is what people genuinely say. Yet on the other hand, people of all classes also say that we have to keep fighting until we win.” One said that “it would be a waste to meaninglessly give back territory people have given their lives for,” another that “the people will not accept it if we gain nothing—either land or reparations. We don’t want to give back what we’ve already spent so much money getting for no reason. Northern China alone will not do. This is the second time we’ve shed blood in Shanghai.”

Here, then, is the picture of a people who, in the midst of their difficult lives, earnestly desired to cooperate in the war because it was their “duty as Japanese,” wishing simultaneously for a swift end to the conflict and to gain privileges from it.

The Profits of War

For the soldiers and their families, conscription and deployment to the front did not bring only suffering. An examination of letters from peasant soldiers who died in battle conducted by the Iwate Prefecture Farming Villages Culture Discussion Association (Iwate ken n?son bunka kondankai) makes clear that from the moment they joined the army, peasant soldiers were liberated from time-consuming and arduous farming chores. With “a daily bath,” “fairly good” food, and “fine shoes,” they led more privileged lives than they had in their farming villages. They received salaries that they could save or send to their families. They were able to enjoy “equal” treatment without regard to their social status or their wealth or poverty. They received education and were able to improve their social standing through their own talents.6

The army was also seen to afford peasant soldiers new prospects. If one became a noncommissioned officer—a corporal or sergeant—through service in the field, the road lay open to becoming a person of influence in one’s village upon return. Soldiers were so eager to make the rank of corporal that teasing of those who remained privates sometimes led to incidents of assault.7