by LYNN NEARY

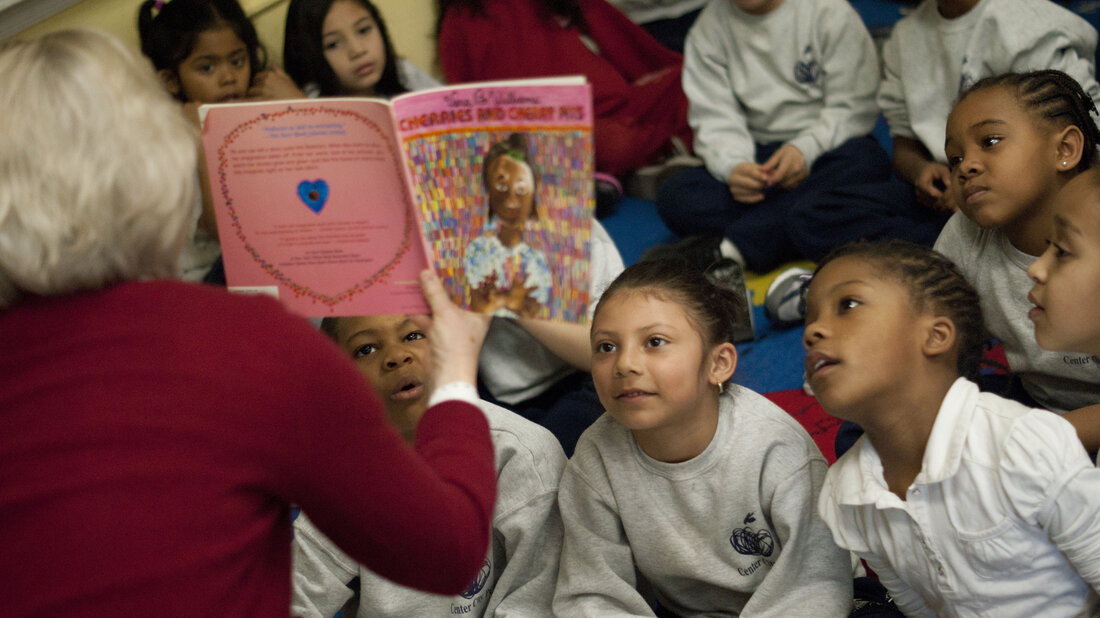

First Book President and CEO Kyle Zimmer reads to children during a book distribution event. PHOTO/First Book

First Book President and CEO Kyle Zimmer reads to children during a book distribution event. PHOTO/First Book

When it comes to learning to read, educators agree: the younger, the better. Children can be exposed to books even before they can talk, but for that a family has to have books, which isn’t always the case.

There are neighborhoods in this country with plenty of books; and then there are neighborhoods where books are harder to find. Almost 15 years ago, Susan Neuman, now a professor at New York University, focused on that discrepancy, in a study that looked at just how many books were available in Philadelphia’s low-income neighborhoods. The results were startling.

“We found a total of 33 books for children in a community of 10,000 children. … Thirty-three books in all of the neighborhood,” she says. By comparison, there were 300 books per child in the city’s affluent communities. Neuman recently updated her study. She hasn’t yet released those findings but says not much has changed.

And according to Neuman, despite advances in technology, access to print books is still important because reading out loud creates an emotional link between parent and child.

“There’s that immediate connection and that eye-to-eye joint attention,” she says. “The parent is not looking at her cellphone or his cellphone; she is focusing on the child and the book. The second reason is the vocabulary that is contained in those books. Even very rudimentary, you know, beginning books, like board books, have vocabulary that tends to be outside the parent’s normal, day-to-day interaction. So that child is learning words that he or she is likely not to see in any other place.”

NPR for more