by NYLA ALI KHAN

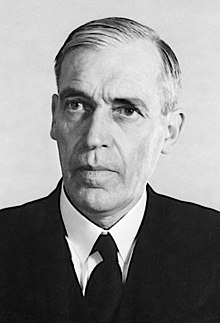

Sir Owen Dixon PHOTO/Wikipedia

Sir Owen Dixon PHOTO/Wikipedia

In the interests of expediency, the UNCIP appointed a single mediator, Sir Owen Dixon, the United Nations representative for India and Pakistan, Australian jurist and wartime ambassador to the United States, to efficiently resolve the Kashmir conflict. Dixon noted, in 1950, that the Kashmir issue was so tumultuous because Kashmir was not a holistic geographic, economic, or demographic entity, but, on the contrary, an aggregate of diverse territories brought under the rule of one maharaja. In a further attempt to resolve the conflict, Sir Owen Dixon propounded the trifurcation of the state along communal or regional lines, or facilitating the secession of parts of the Jhelum Valley to Pakistan.

Despite the bombastic statements and blustering of the governments of both India and Pakistan, however, the Indian government has all along perceived the inclusion of Pakistani-administered J & K and the Northern Areas into India as unfeasible. Likewise, the government of Pakistan has all along either implicitly or explicitly acknowledged the impracticality of including the predominantly Buddhist Ladakh and predominantly Hindu Jammu as part of Pakistan. The coveted area that continues to generate irreconcilable differences between the two governments is the Valley of Kashmir. Dixon lamented:

“None of these suggestions commended themselves to the Prime Minister of India. In the end, I became convinced that India’s agreement would never be obtained to demilitarization in any such form, or to provisions governing the period of the plebiscite of any such character, as would in my opinion permit the plebiscite being conducted in conditions sufficiently guarding against intimidation and other forms of influence and abuse by which the freedom and fairness of the plebiscite might be imperiled.”

(The Statesman, 15 September 1950).

Sir Owen Dixon nonetheless remained determined to formulate a viable solution to the Kashmir issue and suggested that a plebiscite be held only in the Kashmir Valley subsequent to its demilitarization, which would be conducted by an administrative body of UN officials. This proposal was rejected by Pakistan, which, however, reluctantly agreed to Sir Dixon’s further suggestion that the prime ministers of the two countries meet with him to discuss the viability of various solutions to the Kashmir dispute. But India decried this suggestion. A defeated man, Sir Dixon finally left the Indian subcontinent on 23 August 1950. There seemed to be an inexplicable reluctance on both sides, India and Pakistan, to solve the Kashmir dispute diplomatically and amicably. Sir Dixon’s concluding recommendation was a bilateral resolution of the dispute with India and Pakistan as the responsible parties, without taking into account the ability of the Kashmiri people to determine their own political future. Is this the anachronistic policy being toed by the governments of India and Pakistan in 2015?

Nyla Ali Khan can be reached at nylakhan@aol.com