by JEREMY SALT

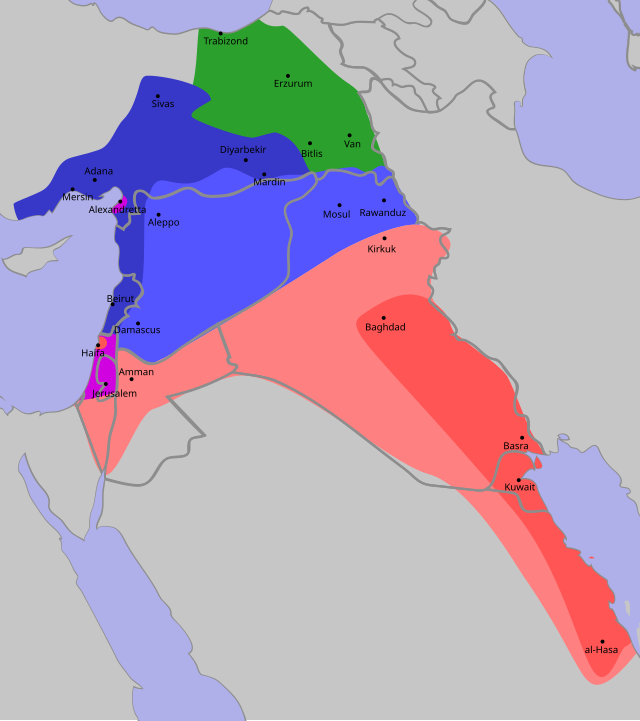

Zones of French (light and dark blue), British (light and dark red) and Russian (green) influence and control established by the Sykes–Picot Agreement. The purple area is an international zone. At a Downing Street meeting of 16 December 1915 Sykes had declared “I should like to draw a line from the e in Acre to the last k in Kirkuk.” MAP/Wikipedia

Zones of French (light and dark blue), British (light and dark red) and Russian (green) influence and control established by the Sykes–Picot Agreement. The purple area is an international zone. At a Downing Street meeting of 16 December 1915 Sykes had declared “I should like to draw a line from the e in Acre to the last k in Kirkuk.” MAP/Wikipedia

French diplomat Francois Georges-Picot (1870-1951) and British politician Mark Sykes (1879-1919) PHOTOS/Wikipedia

French diplomat Francois Georges-Picot (1870-1951) and British politician Mark Sykes (1879-1919) PHOTOS/Wikipedia

Pushing down the wire fence separating Iraq from Syria, the militants of the Islamic State proclaimed jubilantly that Sykes-Picot was dead but was it really they who destroyed Sykes-Picot?

Sykes-Picot was – of course – the First World War agreement by which Britain and France divided the conquered Arab lands of the Ottoman Empire between themselves. The precise boundaries were fixed after the war. France wanted a large Syria, including what is now southeastern Turkey, within a ‘sphere of influence’ stretching as far as Lake Van, but was blocked by the Turkish national resistance and had to settle for less. It then carved Lebanon out of Syria, a decision met with rioting and demonstrations in downtown Beirut and a refusal to fly the cedar flag. Britain, guided by oil interests and seeking domination of the gulf from the north as well as the south, created Iraq out of three distinctive ethno-religious regions, the Kurdish north, the Sunni Arab center and the Shi’a Arab south. Jordan, created out of the original Palestine mandate (not that sharq al Urdun – east of the Jordan – was ever part of historical Palestine), became a British and then a British-American protectorate. Palestine’s political development was put in the deep freeze until such time as the Zionists had the numbers and military force to take it over. Outside the mandates, Iraq and Egypt were given a nominal independence while being brought under the domination of the British through malleable constitutional monarchies and treaties protecting their commercial and strategic interests.

The wave of revolutions in the 1950s – the ‘Arab spring’ of those years – raised expectations that liberation of the entire region was at hand but after Nasser’s death in 1970 the national idea withered on the vine. The present state of the Middle East is probably the worst anyone watching it over a long period of time can probably remember. Indeed, there is nothing as coherent as a ‘Middle East’ any more than that there is anything as coherent as an ‘Arab world’. Instead, there is war, fragmentation, suspicion, rivalries, cowardice, endless bickering and endless dirty deeds being plotted behind closed doors and then carried out, all of them benefitting the common enemy of the Arabs, Israel. ‘Arab history’ is something others are deciding. There are standouts – the resistance of Hizbullah is a shining example – but mostly ‘Arabs’ collectively are not shaping their history at all except by default. How this tragic state of affairs can be turned around no one can say.

The Palestine Chronicle for more