by FRANCIS MULHERN

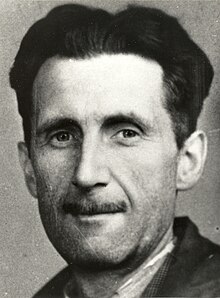

George Orwell (1903-1950), was an English novelist, essayist, journalist, and critic PHOTO/Wikipedia

George Orwell (1903-1950), was an English novelist, essayist, journalist, and critic PHOTO/Wikipedia

The culminating moment was short-lived. By the later 1940s, and arguably sooner, Orwell’s English preoccupations had been overlaid by international politics, above all the geopolitics of the new Cold War. In this rather more than in other respects, Orwell was indeed at one with the Labour government, seconding Bevin’s foreign policy and going so far as to grant the Foreign Office’s propaganda unit—in secret—the benefit of his political assessment of fellow writers. Anti-Communism had been a constant in Orwell’s political thinking since 1935 (the dating is his own) and now it was assuming a new and inescapable objective significance. This, whatever Orwell may have intended and however dismaying to him the upshot, was the conjuncture into which Animal Farm (1945) and Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) were released. The earlier of the two novels, in Colls’s reading, offers a radically pessimistic assessment of both the traditional working class and the new middle class, the teachers, technicians, journalists and other non-manual workers who had long been central to Orwell’s vision of a popular socialist bloc. His beast fable does not say why the animals allow themselves to be robbed of their gains or why the pigs act as they do. It all unfolds as if to show that nature will out. This satire on the Russian Revolution, as Orwell described it in one of his several statements of purpose, is also, in Colls’s estimate, ‘against revolutions in general’. Nineteen Eighty-Four, it might be said, projects the outcome of one revolution in particular: the one announced in The Lion and the Unicorn. The novel ‘envisages the end of England’, the name, the history, the identity and the language. What survives of Englishness is to be found among the proles, from whom, however, the Party has now abstracted itself entirely, creating a parallel reality. The O’Brien figure is intellectuality taken to its anti-English extreme of ‘idealist solipsistic nonsense’. Colls does not quite say as much, but the inference to be drawn is that, in the end, the fundamental opposition in Orwell’s political imagination was England versus Communism. Speculating on the futures that the novelist of Nineteen Eighty-Four did not live to define for himself, he writes: ‘the signs are he would have been a Cold Warrior’. By 1949, the signs were he already was.

New Left Review for more