A reply to the Mahatma

by B. R. AMBEDKAR

9.1 Some might think that the Mahatma has made much progress, inasmuch as he now only believes in varna and does not believe in caste. It is true that there was a time when the Mahatma was a full-blooded and a blue-blooded sanatani Hindu. [2] He believed in the Vedas, the Upanishads, the puranas, and all that goes by the name of Hindu scriptures; and therefore, in avatars and rebirth. He believed in caste and defended it with the vigour of the orthodox. [3] He condemned the cry for inter-dining, inter-drinking, and intermarrying, and argued that restraints about inter-dining to a great extent “helped the cultivation of will-power and the conservation of a certain social virtue.”

…

9.9 The second source of confusion is the double role which the Mahatma wants to play—of a Mahatma and a politician. As a Mahatma, he may be trying to spiritualise politics. Whether he has succeeded in it or not, politics has certainly commercialised him. A politician must know that society cannot bear the whole truth, and that he must not speak the whole truth; if he is speaking the whole truth it is bad for his politics. The reason why the Mahatma is always supporting caste and varna is because he is afraid that if he opposed them he would lose his place in politics. Whatever may be the source of this confusion, the Mahatma must be told that he is deceiving himself, and also deceiving the people, by preaching caste under the name of varna.

10.1 The Mahatma says that the standards I have applied to test Hindus and Hinduism are too severe, and that judged by those standards every known living faith will probably fail. The complaint that my standards are high may be true. But the question is not whether they are high or whether they are low. The question is whether they are the right standards to apply. A people and their religion must be judged by social standards based on social ethics. No other standard would have any meaning, if religion is held to be a necessary good for the well-being of the people.

Outlook for more

“We need Ambedkar–now, urgently…”

SABA NAQVI interviews ARUNDHATI ROY

“Arundhati Roy, now a good deal more than a successful novelist, spoke at the Jamia Millia Islamia university in Delhi on Gandhi in South Africa, with Ambedkar being mentioned in passing.” PHOTO/Mukul Dube/Flickr

“Arundhati Roy, now a good deal more than a successful novelist, spoke at the Jamia Millia Islamia university in Delhi on Gandhi in South Africa, with Ambedkar being mentioned in passing.” PHOTO/Mukul Dube/Flickr

Have you always held these views about Gandhi, or did you discover new aspects to him as you explored him vis-a-vis Ambedkar?

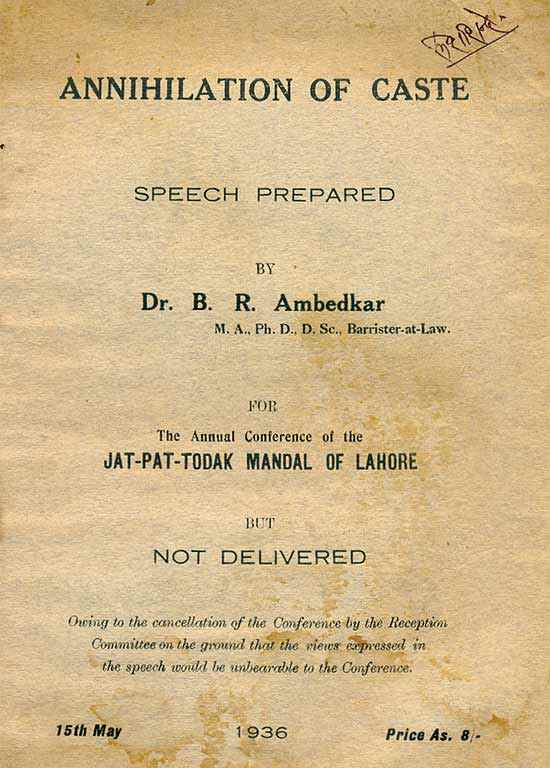

I am not naturally drawn to piety, particularly when it becomes a political manifesto. I mean, for heaven’s sake, Gandhi called eating a “filthy act” and sex a “poison worse than snake-bite”. Of course, he was prescient in his understanding of the toll that the Western idea of modernity and “development” was going to take on the earth and its inhabitants. On the other hand, his Doctrine of Trusteeship, in which he says that the rich should be left in possession of their wealth and be trusted to use it for the welfare of the poor—what we call Corporate Social Responsibility today—cannot possibly be taken seriously. His attitude to women has always made me uncomfortable. But on the subject of caste and Gandhi’s attitude towards it, I was woolly and unclear. Reading Annihilation of Caste prompted me to read Ambedkar’s What Congress and Gandhi Have Done to the Untouchables. I was very disturbed by that. I then began to read Gandhi—his letters, his articles in the papers—tracing his views on caste right from 1909 when he wrote his most famous tract, Hind Swaraj. In the months it took me to research and write The Doctor and the Saint I couldn’t believe some of the things I was reading. Look—Gandhi was a complex figure. We should have the courage to see him for what he really was, a brilliant politician, a fascinating, flawed human being—and those flaws were not to do with just his personal life or his role as a husband and father. If we want to celebrate him, we must have the courage to celebrate him for what he was. Not some imagined, constructed idea we have of him.

Outlook for more

The doctor and the saint

by ARUNDHATI ROY

Today, India’s one hundred richest people own assets equivalent to one-fourth of its celebrated GDP. [1] In a nation of 1.2 billion, more than 800 million people live on less than Rs20 a day. [2] Giant corporations virtually own and run the country. Politicians and political parties have begun to function as subsidiary holdings of big business.

…

A recent list of dollar billionaires published by Forbes magazine features 55 Indians. [4] The figures, naturally, are based on revealed wealth. Even among these dollar billionaires the distribution of wealth is a steep pyramid in which the cumulative wealth of the top 10 outstrips the 45 below them. Seven out of those top 10 are Vaishyas, all of them ceos of major corporations with business interests all over the world. Between them they own and operate ports, mines, oil fields, gas fields, shipping companies, pharmaceutical companies, telephone networks, petrochemical plants, aluminium plants, cellphone networks, television channels, fresh food outlets, high schools, film production companies, stem cell storage systems, electricity supply networks and Special Economic Zones. They are: Mukesh Ambani (Reliance Industries Limited), Lakshmi Mittal (Arcelor Mittal), Dilip Shanghvi (Sun Pharmaceuticals), the Ruia brothers (Ruia Group), K.M. Birla (Aditya Birla Group), Savitri Devi Jindal (O.P. Jindal Group), Gautam Adani (Adani Group), and Sunil Mittal (Bharti Airtel). Of the remaining 45, 19 are Vaishyas too. The rest are for the most part Parsis, Bohras and Khattris (all mercantile castes) and Brahmins. There are no Dalits or Adivasis in this list.

Outlook for more