by ADAM SHATZ

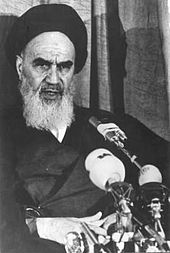

Ruhollah Mostafavi Musavi Khomeini (1902-1989) giving a speech in 1979 PHOTO/Wikipedia

Ruhollah Mostafavi Musavi Khomeini (1902-1989) giving a speech in 1979 PHOTO/Wikipedia

Days of God: The Revolution in Iran and Its Consequences by James Buchan

John Murray, 482 pp, £25.00, November 2012, ISBN 978 1 84854 066 8

At the end of the Second World War, an anonymous pamphlet surfaced in the seminaries of Qom, the bastion of Shia learning. The Unveiling of Secrets accused Iran’s monarchy of treason: ‘In your European hats, you strolled the boulevards, ogling the naked girls, and thought yourselves fine fellows, unaware that foreigners were carting off the country’s patrimony and resources.’ Iran, it proposed, should be ruled by an assembly of religious jurists headed by a wise man. In such a state, there would be no need for elections or a parliament, or even a standing army: a religious militia (basij) would ensure obedience to the law.

It’s unlikely that anyone outside Qom read The Unveiling of Secrets; even inside the seminaries few would have embraced its programme. Yet just three decades later the pamphlet’s author, Ruhollah Khomeini, helped launch a revolution against the monarchy and established himself as Iran’s supreme leader, with powers even the shah would have envied. The political landscape was transformed: the Shia of Iran, a minority in the house of Islam, had rewritten the script of revolution in the Middle East. James Buchan’s Days of God shows how a radicalised clergy took control of a popular uprising against a Western-backed dictator and set up the world’s first and only Islamic republic. Buchan tells that story as well as anyone has done, but Days of God is also an erudite reflection on three important questions: why there was a revolution, why it was Islamic and what its legacy has been. The Iranian Revolution was, Buchan argues, a revolt against Western-imposed modernisation in favour of an enchanted path to modernity. It had a spiritual aim that grew out of the history of Shiism, with its themes of martyrdom and redemption, but the attempt to infuse governance with divine authority ended up expanding – and ultimately sanctifying – the authoritarian state the clerics inherited from the shah. ‘In revolt against Pahlavism,’ Buchan writes, ‘the Islamic republic is also its continuation in turban and cloak.’

London Review of Books for more