by AIJAZ AHMAD

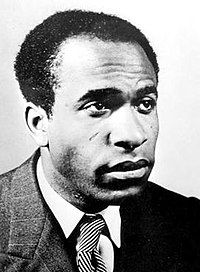

Writer, revolutionary, philosopher, and psychiatrist Frantz Fanon (1925-1961) PHOTO/Wikipedia

Writer, revolutionary, philosopher, and psychiatrist Frantz Fanon (1925-1961) PHOTO/Wikipedia

Frantz Fanon, who dedicated the closing years of his life to the revolution in Algeria, was a thinker of original insights and a psychiatrist who used his knowledge as an instrument for healing the victims of oppression.

THE current year, 2012, marks the 50th anniversary of the death of Frantz Fanon, one of the indispensable figures of the 20th century and a man of exemplary commitments to revolutionary action and human liberation. A thinker who offered original and lasting insights of great complexity, he was also a physician and a psychiatrist who used his scientific knowledge not just for professional purposes but as an instrument for healing victims of oppression and violence.

Born in Martinique and educated in France, Fanon dedicated the closing years of his life to the revolution in Algeria. During the revolutionary waves of the 1960s and early 1970s, he was read and revered by hundreds of thousands across the globe. As those waves receded, as so many of the formerly revolutionary regimes degenerated into dictatorships, and as neoliberal triumphalism marched across the world, it was in the interests of those in power—be they white, black or brown—to consign his memory to obscurity. Scholar-activists of today have a duty to renew the visions, the analyses and the warnings he offered roughly half a century ago.

Fanon’s was a short life, lasting just over 36 years. Given his protean brilliance, one has the impression of a lightning flash, or a series of such flashes over less than a decade, from 1952, when his first masterpiece, Black Skin, White Masks, was published, and 1961, the year of his much-too-early death from leukaemia as well as the publication of his last masterpiece, The Wretched of the Earth. Encompassing such flashes of genius, however, is a variety of contexts and involvements—as philosopher, psychiatrist and revolutionary internationalist; and from the Caribbean to Europe to the Maghreb to West Africa—that gives one the sense of something resembling an oceanic immensity. In the following pages we shall be concerned with Fanon mostly as a thinker and less as revolutionary militant even though these two aspects of his life are inseparable. Issues related to his Algerian involvements will inevitably come up, but any serious account of it would make this introductory essay much too long.

Immanuel Wallerstein, the noted American author and theorist, knew him and held lengthy discussions with him in Accra, where Fanon had been sent as envoy by the Gouvernement Provisoire de la Republique Algerienne (GPRA) in the course of the Algerian revolution. We can take his characterisation of Fanon as emblematic of how difficult it is to encapsulate the complexity of Fanon in a few words. Wallerstein writes: “He might rather be characterised as one part Marxist Freudian, one part Freudian Marxist and most part totally committed to revolutionary liberation movements.” Wallerstein is absolutely correct about Fanon’s total commitment to revolutionary liberation during the closing years of his life, a matter to which we shall return. However, he is only partially right about Fanon’s purported “Freudian” and “Marxist” orientations. I will ignore the issue of Freud here but that of Marx needs some comment.

Class, nation & race

Marxism was very much a part of the air that Fanon breathed through his formative years in Martinique in the company of such people as Aime Cesaire, the great poet; during his years in France and his association with people like Henri Jeanson and Jean-Paul Sartre; and in those particular circles of the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN) with which he was most closely associated. He quotes and paraphrases Marx freely in his writings, and even the title of his legendary last book, which he dictated when he knew he was going to die soon, was taken from the Internationale, the proletarian anthem of the world communist movement. However, Marxism for him was refracted through many a prism. Philosophically, his brand of Marxism was suffused with Hegelian Dialectics, Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology as well as the existentialism of Heidegger and Sartre, especially the latter. The great philosophical eminence behind his youthful book, Black Skin, White Masks, is Hegel, not Marx. Secondly, he levelled the same charge against Marxism and communism that many other writers of Afro-Caribbean and Afro-American origins, notably his friends Cesaire and Richard Wright, had brought up. They had argued that colonialism was constitutive of the capitalist modern world, that racism was the constitutive ideology and practice of colonialism, and that the philosophical and political traditions descended from Marxism did not take racism seriously enough, as something intrinsic to the social relations of capitalism and imperialism on the global scale. Fanon further asserted that in the political context of colonialism, the category of nation had primacy over the category of class, and that in the socio-economic structure of African/Caribbean societies (he sometimes said all colonial societies) the peasantry and the lumpen proletariat were more revolutionary than the proletariat per se; in this view of the lumpen proletariat in particular, he ran quite counter to virtually every tendency within Marxism. All in all, one can say that Fanon was still in search of a coherent theory, of which Marxism would be a major component, when death cut short his brilliant quest. The brevity of his life stands in sharp contrast to the variety of his contexts and involvements, intellectual as well as political. Here we shall first offer a brief sketch of his life and will then comment on certain themes and categories that are fundamental to his magisterial thought.

Early influences

Born in Martinique and with Aime Cesaire as his mentor and close friend, Afro-Caribbean philosophical and literary traditions were Fanon’s first and lasting intellectual nursery that included such outstanding figures as Edourd Glissant, Wilson Harris, George Padmore, C.L.R. James and the brilliant, albeit little-known, Haitian ethnologist Jean-Price Mars. These influences inclined him toward the Left quite early in his youth, reinforced by his encounter with that part of the Afro-American literary world of the United States that was represented at the time by such authors as Langston Hughes and Richard Wright. Together, this whole range of writers gave Fanon a keen sense of the contradiction between the philosophical and cultural grandeur of European bourgeois civilisation on the one hand and, on the other, the triple savagery of slavery, colonialism and racism that the same civilisation had perpetrated across the globe. If the themes of his Black Skin, White Masks (1952) overlapped with those of Cesaire’s landmark poem Return to My Native Land (1939; 1947) and his subsequent Discourse on Colonialism (1955), it equally converges with Richard Wright’s White Man, Listen! (1957).

That intellectual formation was also grounded for Fanon in the actual experience of the colonialists’ pervasive racism not only in Martinique—a colony which the ruling French nevertheless described as an outlying “province” of France—but even in the French Free Forces that had been assembled under Charles De Gaulle’s leadership against the Nazi occupation of France during the Second World War, and in which Fanon had enlisted at the age of 18 as an opponent of fascism. Upon his return to Martinique in 1945, he worked for the electoral campaign of Cesaire, who was running on a communist ticket for the position of a deputy from Martinique in the first National Assembly of the French Fourth Republic. As these facts would testify, Fanon’s radical stance—anti-Nazi, with communist sympathies—and his belief that one has to fight actively for what one believes and preaches were already well formed by the time he took his baccalaureate and sailed to France for higher education.

Frontline for more