by JEFFREY ST. CLAIR

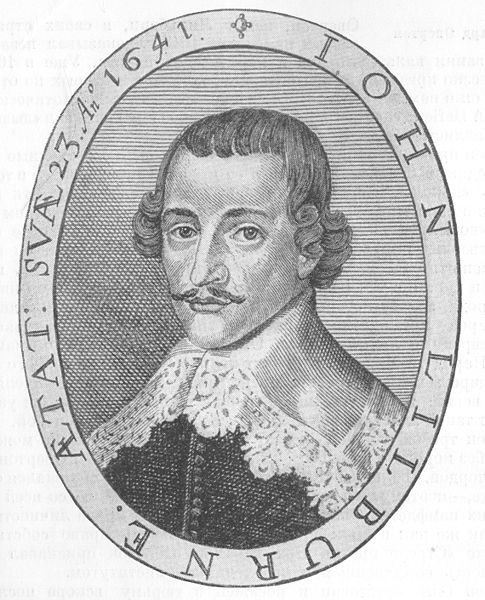

John Lilburne. SOURCE/Wikipedia

John Lilburne. SOURCE/Wikipedia

In 1638, John Lilburne was put on secret trial by the Star Chamber of Charles I. His crime? The writing and distribution of seditious pamphlets that skewered the legitimacy of the monarchy and challenged the primacy of the high prelates of the Church of England. He was promptly convicted of publishing writing of “dangerous consequence and evil effect.”

For these intolerable opinions, the royal tribunal sentenced him to be publicly flogged through the streets of London, from Fleet Prison, built on the tidal flats where Fleet Ditch spilled out London’s sewage, to the Palace Yard at Westminster, then a kind of public showground for weekly spectacles of humiliation and torture. By one account, Lilburne was whipped by the King’s executioner more than 500 hundred times, “causing his shoulders to swell almost as big as a penny loafe with the bruses of the knotted Cords.”

The bloodied writer was then shackled to a pillory, where, to the amazement of the crowd of onlookers, he launched into an impassioned oration in defense of his friend Dr. John Bastick, the puritan physician and preacher. Only weeks before, Bastick’s ears had been slashed off by the King’s men as punishment for publishing an attack on the Archbishop of Canterbury, an essay that Lilburne had happily distributed far and wide. Lilburne gushered forth about this barbaric injustice for a few moments, before his tormentors gagged his mouth with a urine soaked rag. After enduring another two hours of torture, the guards dragged him behind a cart back to the Fleet, where he was confined in irons for the next two-and-a-half years. This was the first of “Free-Born” John Lilburne’s many parries with the masters of Empire.

While in his foul cell in Fleet prison, Lilburne was kept in solitary confinement on orders of the Star Council, his lone visitor a maid named Katherine Hadley. Somehow the maid was able to sneak pen, paper and ink past the Fleet’s guards to the young radical. According to Lilburne’s own description, he was “lying day and night in Fetters of Iron, both hands and legges,” when he began to write furiously, penning a gruesome account of his mock trial and torture, The Work of the Beast, and a scabrous assault on the Anglican bishops, Come Out of Her, My People. These pamphlets were smuggled out of Newgate, printed in the LowLands and distributed through covert networks across England to popular acclaim and royal indignation.

Oliver Cromwell, then a Puritan leader in the House of Commons, took up Lilburne’s cause, giving a stirring speech in defense of the imprisoned writer. It swayed Parliament, which voted to release Lilburne from jail. Lilburne emerged from prison grateful to Cromwell, but not blind to the general’s dictatorial ambitions: he would later pen savage attacks on Cromwell and his censorious functionaries.

Counterpunch for more