by MARK W. POST

If you have studied almost any European language, you will have noticed words that felt oddly familiar. French mort (dead) recalls English murder. German Hund (dog) is a dead ringer for hound. Czech sestra resembles English sister. No prizes for guessing the meaning of Albanian kau (OK, well – it’s actually ox).

You might have wondered: could these words be in some way related?

Of course, words can look similar for various reasons. Unrelated languages borrow from one another: consider English igloo, from Inuktikut iglu (house), or wok from Cantonese ? wòk (frying pan). And there are plenty of sheer coincidences: Thai ?? fai resembles its English translation fire for no particular reason at all.

But the preceding sets of words actually are related to one another. They are cognate, which means they share a common origin in descent from a single ancestral language.

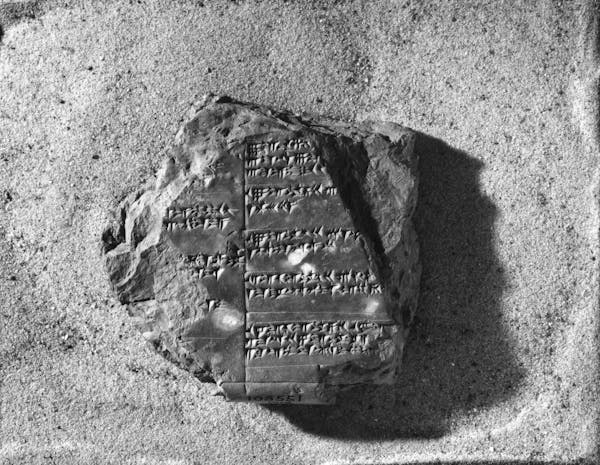

This now-extinct tongue was probably spoken somewhere in Eurasia as many as 8,000 years ago. Long predating the advent of writing systems, its words – and its name, if it had one – were never written down. Lacking such direct knowledge, linguists have therefore developed methods for reconstructing aspects of its structure, and refer to it using the label Proto-Indo-European – or PIE.

But how do we know Proto-Indo-European must have existed?

Shared ancestry of language

Our modern-day awareness of the shared ancestry of Indo-European languages first took shape in the Renaissance and early colonial periods.

India-based European scholars such as Gaston Coeurdoux and William Jones were already familiar with the ties among European languages.

But they were astonished to find echoes of Latin, Greek and German in Sanskrit words such as m??t? (mother), bhr??t? (brother) and dúhit? (daughter).

Such words could not plausibly be borrowings, given these languages’ lack of historical contact. Sheer coincidence was obviously out of the question.

Even more striking was the systematic nature of the correspondences. Sanskrit bh- matched Germanic b- not only in bhr??t? (brother) but also in bhar (bear). Meanwhile, Sanskrit p- aligned with Latin and Greek p-, but with Germanic f-.

There could be only one explanation for such regular correspondences. The languages must have descended from a single common ancestor, whose ancient breakup led to their distinct evolutionary pathways.

Philologists from the 19th century, such as Rasmus Rask, Franz Bopp and August Schleicher, later systematised these observations. They showed that, by comparing and reverse-engineering the changes each descendant language’s words had undergone, the words of the lost ancestral language could be reconstructed.

These insights not only laid the foundations of modern-day historical linguistics, but also went on to influence Darwin’s conception of biological evolution.

The Conversation for more