by MAURIZIO VALSANIA

The day after conservative activist Charlie Kirk was shot and killed while speaking at Utah Valley University, commentators repeated a familiar refrain: “This isn’t who we are as Americans.”

Others similarly weighed in. Whoopi Goldberg on “The View” declared that Americans solve political disagreements peacefully: “This is not the way we do it.”

Yet other awful episodes come immediately to mind: President John F. Kennedy was shot and killed on Nov. 22, 1963. More recently, on June 14, 2025, Melissa Hortman, speaker emerita of the Minnesota House of Representatives, was shot and killed at her home, along with her husband and their golden retriever.

As a historian of the early republic, I believe that seeing this violence in America as distinct “episodes” is wrong.

Instead, they reflect a recurrent pattern.

American politics has long personalized its violence. Time and again, history’s advance has been imagined to depend on silencing or destroying a single figure – the rival who becomes the ultimate, despicable foe.

Hence, to claim that such shootings betray “who we are” is to forget that the U.S. was founded upon – and has long been sustained by – this very form of political violence.

Revolutionary violence as political theater

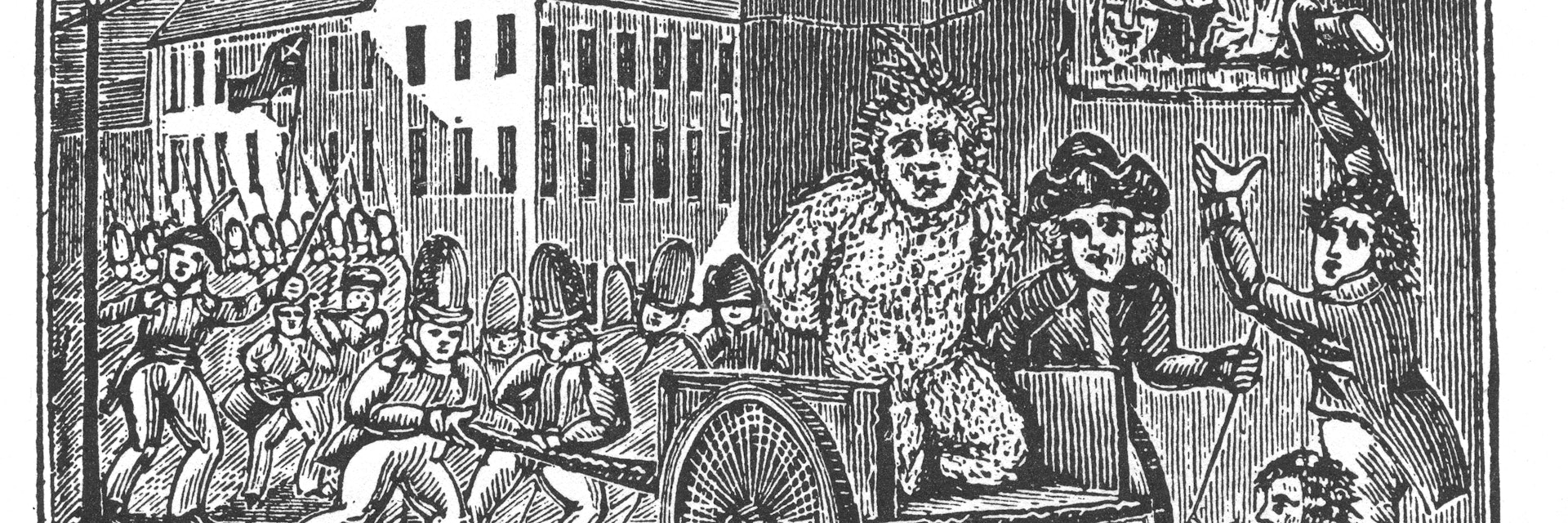

The years of the American Revolution were incubated in violence. One abominable practice used on political adversaries was tarring and feathering. It was a punishment imported from Europe and popularized by the Sons of Liberty in the late 1760s, Colonial activists who resisted British rule.

In seaport towns such as Boston and New York, mobs stripped political enemies, usually suspected loyalists – supporters of British rule – or officials representing the king, smeared them with hot tar, rolled them in feathers, and paraded them through the streets.

The effects on bodies were devastating. As the tar was peeled away, flesh came off in strips. People would survive the punishment, but they would carry the scars for the rest of their life.

By the late 1770s, the Revolution in what is known as the Middle Colonies had become a brutal civil war. In New York and New Jersey, patriot militias, loyalist partisans and British regulars raided across county lines, targeting farms and neighbors. When patriot forces captured loyalist irregulars – often called “Tories” or “refugees” – they frequently treated them not as prisoners of war but as traitors, executing them swiftly, usually by hanging.

In September 1779, six loyalists were caught near Hackensack, New Jersey. They were hanged without trial by patriot militia. Similarly, in October 1779, two suspected Tory spies captured in the Hudson Highlands were shot on the spot, their execution justified as punishment for treason.

To patriots, these killings were deterrence; to loyalists, they were murder. Either way, they were unmistakably political, eliminating enemies whose “crime” was allegiance to the wrong side.

The Conversation for more