by SIBTAIN NAQVI

Poets today are happy to remain part of a convivial fraternity. With little patronage to compete for and minimal ideological divide, the desire for rhyming ripostes and public put-downs hardly exists. It wasn’t always so. Previously poets were often rivals and lost no opportunity in exchanging barbs couched in deadly but exquisite eloquence.

Muhammed Ibrahim Zauq and Mirza Asadullah Baig Khan, better known as Ghalib, were bitter rivals, for example, and unleashed several lyrical fusillades against each other to win Mughal emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar’s favours. From the days of Ghalib, mushairas (poetry recitals) were not just a platform for dissent against the state, but also opportunities to protest against other members of the poetic community to highlight ideological differences.

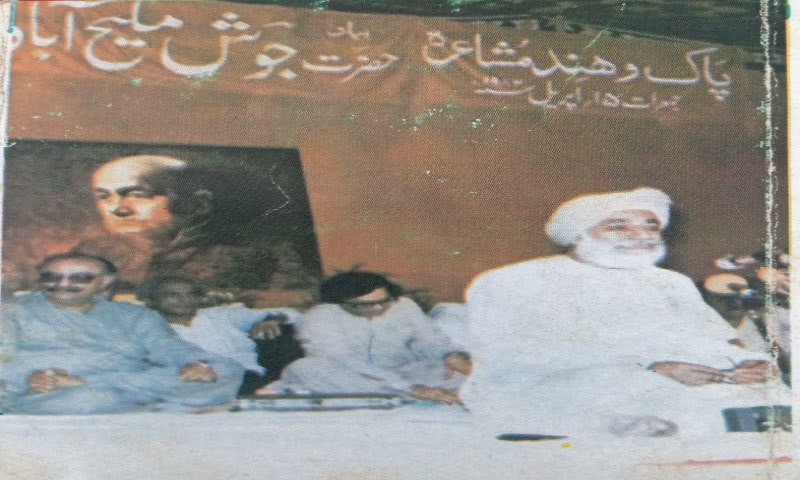

Among the more recent examples of such poetic friction was the Bayaad-i-Josh mushaira held on April 13, 1982. Organised by the Anjuman-i-Saadat-i-Amroha at a time of great censorship because of Gen Zia’s dictatorial regime, it was a memorial for Josh Malihabadi, whose death on February 22, 1982 had been ignored by the state. Members of the Amrohvi community in Karachi had the intellectual gravitas to brave the political backlash. The event featured some of the greatest Urdu poets of the time, who were witness to an episode that highlighted the ideological differences of Josh Malihabadi and Hafeez Jalandhari, one a fierce critic of dictators and the other a close supporter.

Josh Malihabadi had immigrated to Pakistan several years after Partition and was never at ease in his new country. He had been a part of India’s intellectual elite, and a darling of the Congress leadership. So iconic was Josh in India that Vijay, the protagonist from Guru Dutt’s cult classic Pyaasa, wants to be a revolutionary poet just like Josh. Vijay snubs the more populist genre of romantic poetry, for which he suffers great hardship.

Despite his position in India, Josh gave in to the entreaties of A.T. Naqvi, commissioner of Karachi, who had told him, “Josh Sahib, you can’t cross a river with your feet anchored in two boats.” Against the advice of Indian PM Jawaharlal Nehru, who gave him the option to move back and forth between the two countries, Josh left India thinking that Urdu would be ignored there because of the “narrow-minded nationalism of Hindus.” In 1955, he crossed the border and, soon after, became a fierce critic of the military dictatorship of Ayub Khan. For this he faced endless problems, becoming the target of right-wingers while his property was confiscated by the regime. His poetry too did not get the requisite recognition from the state.

On the other side of the political divide were pro-establishment writers and poets, chief among them Hafeez Jalandhari, the poet laureate, who had also penned Pakistan’s national anthem. Their ideological divide was stark. Josh hated the British and sported the Führer’s moustache to remind them of their bête noire. In his poem East India Company Ke Farzandon Se Khitab [Address to the Heirs of the East India Company], Josh had lambasted British hypocrisy and recounted their crimes, from the battle of Plassey in 1757 to hanging the revolutionary Bhagat Singh in 1931. Invoking the powerful imagery of Karbala, he had addressed their apologists:

Mujrimon ke waastay zeba nahin ye shor-o-shain

Kal Yazeed-o-Shimr thhey aur aaj bantay ho Hussain!

[This hue and cry does not suit the defence of criminals/ You who were Yazeed and Shimr yesterday pretend today to be Hussain!]

Like anti-British revolutionary Subhas Chandra Bose, who was even willing to ally himself with fascists to gain independence for India, Josh considered the British to be the ultimate enemy and published this poem in 1939 as the British were exploiting India in preparation for World War II.

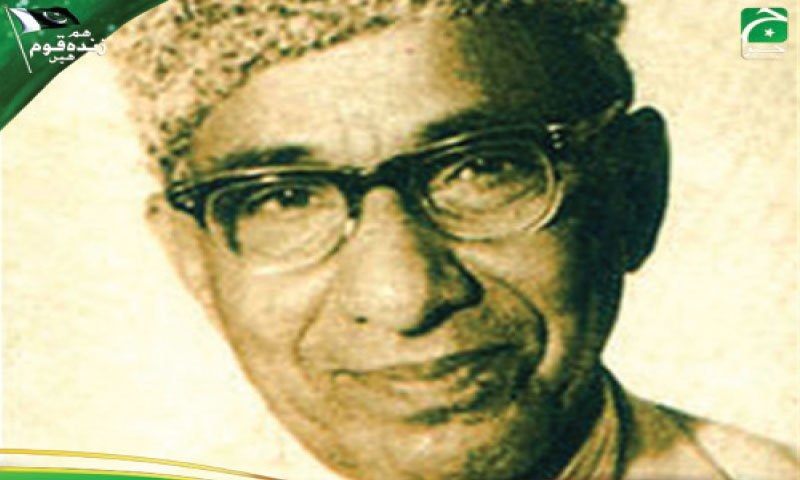

Meanwhile, Hafeez Jalandhari was using his pen to support the British war effort. During World War II, as the head of the Bureau of Public Information and Song Publicity Organisation at All India Radio, Jalandhari played an important role for British propaganda. According to several accounts, he wrote poems such as Boot to recruit Indian cannon fodder that would eventually die in North Africa and East Asia for their colonial masters:

Idhar pehno ho tooti jooti, udhar pehno ge boot

Bharti ho jao!

[Here you wear a broken slipper, there you will get a fancy boot/ Go join the army!]

Dawn for more