by ANN GARRISON

Eritrea remains true to the revolutionary ideals forged during its 30-year War of Independence.

On May 24th, Eritrea celebrated its 34th Independence Day. From September 1, 1961, to May 24, 1991, the Eritrean people waged a 30-year war to free themselves from the Ethiopian empire, first under the control of Emperor Haile Selassie and then under the Derg regime’s Mengistu Haile Mariam.

Eritrea was the first of five African nations now refusing to collaborate with AFRICOM , the US Africa Command. It has also refused to saddle itself with IMF or World Bank debt, but the African Development Bank has praised its progress and provided funding for one of its renewable energy projects and for its education initiatives.

I spoke to Eritrean-American journalist Elias Amare , who hosts his own YouTube channel , most of which is in the Tigrinya language, about Eritrea’s hard won independence.

ANN GARRISON: Elias, I know it’s difficult to summarize 30 years, but nevertheless, can you tell us the salient points we might understand about the Eritrean independence struggle, including the process that led to UN recognition?

ELIAS AMARE: That

is a tall order, but let me start with some personal connection. I was

born the year the armed struggle for national liberation was launched in

Eritrea, in 1961, so my entire life has been within the struggle, first

to liberate the land and, secondly, to defend the Eritrean sovereignty

that was won with huge sacrifices, both human and material, during the

30-year struggle.

First we must bear in mind that the armed struggle was launched by

Eritreans only when all peaceful political avenues had been closed to

it. Eritrean demands and protests for national self-determination had

just led to more deaths and more repression. In 1961, a band of armed

men led by Hamid Idris Awate and inspired by the Algerian national liberation struggle finally launched the armed struggle.

Sectarianism and division along narrow, ethnic, and religious lines haunted the early movement until a progressive vision emerged. It was established that the leadership of the armed struggle had to be within Eritrea, on the battlefield, not sitting outside in comfortable zones like Cairo or Sudan, and that religious and ethnic divides had to be set aside for the sake of the national struggle.

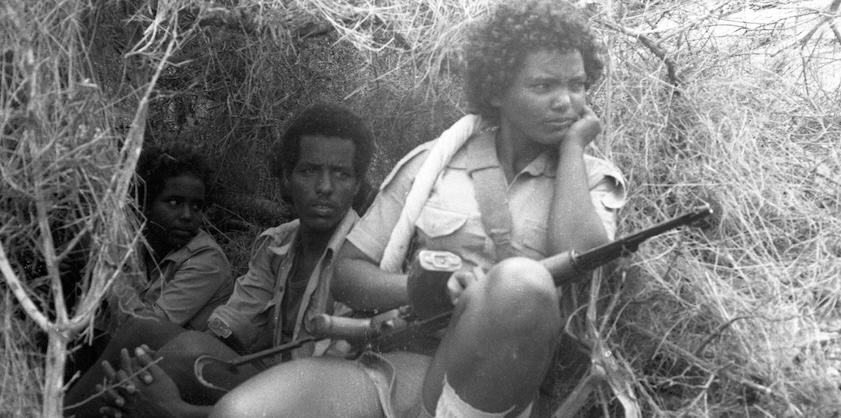

The movement also prioritized popular democracy emerging from feudalistic culture, with political education, eradication of illiteracy, equality among fighters, and strict egalitarianism. Leaders and the rank and file had the same living standards; they shared the same accommodations, ate the same food, and received the same medical attention as needed. Their children got the same education.

There was popular democratic debate, criticism, and self-criticism. The emancipation of women was also prioritized, and that was extremely revolutionary within the patriarchal societies of that time.

This process gave birth to the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front, and the egalitarian principles it established have carried through to this day.

On May 24, 1991, after the sacrifice of 65,000 heroic Eritrean fighters, the EPLF finally defeated the Ethiopian army, whose troops gave up and fled, with some even heading into Sudan.

The Eritreans never took any vendetta against them. They even gave them food and water along their way. All they wanted was a peaceful end to the war.

The Ethiopian Derg regime collapsed at the same time, and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) took over. Eritreans had fought with the TPLF in the interest of defeating a common enemy.

Once EPLF had established de facto control of Eritrean territory, it established a transitional government. Then, in 1993, there was a referendum on becoming an independent nation that was monitored by the United Nations and other international observers. There was no question that this was a free and fair election, and Eritreans voted for independence by 99.85%. The official declaration was delayed until May 24, 1993, because we wanted our independence to coincide with the day we defeated the Ethiopian army.

Within minutes of the declaration of independence, after the results of the referendum, five countries stepped forward– Egypt, Sudan, Italy, and the United States–to recognize Eritrea. The United States had opposed Eritrean independence since the 1940s, but it finally accepted the reality on the ground and became one of the first countries to officially recognize us. After that, the floodgates opened, and one country after another recognized.

On May 28, 1993, Eritrea was officially admitted as the 182nd UN member state. I was part of the Eritrean delegation that officially went to the United Nations when Eritrea was officially accepted as a free, independent nation, and it was the most moving experience of my life to see the Eritrean flag being raised in front of the UN after a 30-year struggle. Tears of pride, tears of joy, rushed down my face.

AG: I believe that meant that, in accordance with the UN Charter, the Security Council had passed a resolution to recommend recognition to the UN General Assembly, with at least nine votes and no vetoes from the five permanent members, and then the General Assembly had voted to recognize by at least a two-thirds majority.

EA: Yes, I believe that’s the procedure.

Black Agenda Report for more