VIDEO/Shemaroo Films/Youtube

Shyam Benegal (1934-2024): A compassionate critic of the evolving history of post-Independent India

by ARUN SENGUPTA

d away at 90, learnt his craft in the most unlikely way. | Photo Credit: AFP

Shyam Benegal’s love for films started when he was a child. His appetite for them was voracious. When he couldn’t afford to watch them, he befriended the projectionist of his local cinema and watched them through his window. Sometimes he and his friend wedged the door open a crack so he could see the movie. It wasn’t comfortable but it didn’t matter. Those flickering shadows held him in thrall.

When Benegal grew up, he quickly realised he couldn’t make the films that he wanted to, and so he waited until he could open new windows for himself. And in the process, he changed Indian cinema in fundamental ways.

While researching for my book on him, my publisher sent me his number and asked me request him for an interview. He was busy with post-production work on Mujib: The Making of a Nation, but graciously gave me a couple of days at his office in Tardeo, Mumbai. He patiently answered all my questions for hours.

Benegal was a man of quiet, unassuming erudition. Surrounded by books in his cosy office, he could easily be mistaken for an emeritus professor. After every question, he would pause, collect his thoughts before answering. While talking to him I was struck by a strange paradox: he had dedicated his life to making serious cinema but didn’t take himself or even the medium too seriously. When I asked him about the unavailability of many of his films, he chuckled and said that films are commodities with short lifespans. This strong streak of practicality is perhaps why his films are complex, thought-provoking but never pretentious.

Benegal’s love for the medium came first. His childhood was spent in Trimulgherry, a cantonment in Secunderabad. It was here that he decided he will be a filmmaker when he was just ten. He found films to be extremely immersive, a form that can transport one into a different world. It evokes immediate visceral responses, like when he witnessed the first jump scare in cinema in Jacques Tourneur’s Cat People in 1942. Later, he made films with strong messages, but he never let it overwhelm the artistry of the medium.

He, in fact, learnt the craft in the most unlikely way. His cousin, Guru Dutt, who had made a name for himself in the industry, had offered him a job as an assistant director. But he refused: he didn’t care much for commercial cinema because it was, at best, a product of compromise or, at worst, escapist fluff of no real value. Instead, he moved to Bombay and joined the National Advertising Agency. He not only made hundreds of ad films but was also asked to take them by road all over the northeast from Jorhat, Assam. His knowledge of advertising distribution networks came in handy when he had to bypass traditional film distribution circuits for his first film.

Intrigued by the form

Frontline for more

A Legacy of Courage, Authenticity and Humanity: Shyam Benegal (1934-2024)

by SHAHREZAD SAMIUDDIN

Shyam Benegal wasn’t just a director; he was a storyteller who reshaped the filmmaking in India. Recognised as a towering figure in Indian cinema, Shyam Benegal passed away on December 23, 2024, at the age of 90. According to his daughter, he succumbed to a chronic kidney disease, a condition he had been battling for years. With his passing, Indian cinema has lost a visionary director who gave voice to many untold narratives.

Born on December 14, 1934, in Hyderabad (Telangana), Benegal discovered his love for storytelling at a young age. When he was 12 years old, he had made his first short film, Chuttiyon Mein Mauj-Maza, which was shot on a camera gifted to him by his father.

This experiment was a small glimpse of the remarkable career that lay ahead of him. It would be a journey that would merge his curiosity about the human condition with his cinematic genius.

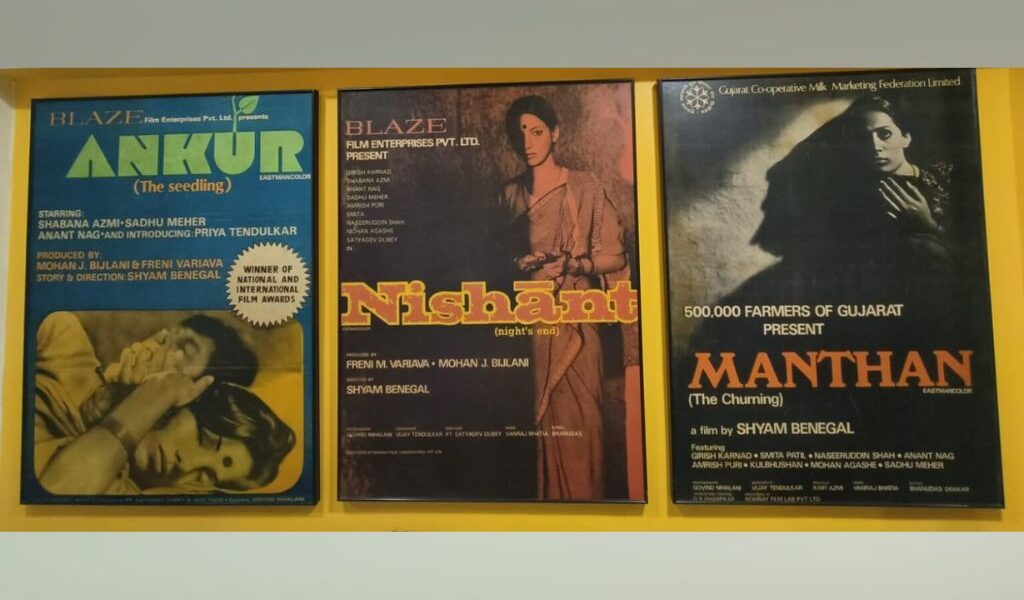

Benegal began his professional journey working in advertising, directing commercials. This format allowed him to hone his skills before he set out to follow his heart and try his hand at directing feature films. His debut film, Ankur (1973), was an exploration of caste and gender dynamics in rural India and introduced audiences to Shabana Azmi, who would go on to become one of the most revered actors in Indian cinema. The film’s unflinching honesty foretold Benegal’s future as a formidable filmmaker.

After Ankur, his next works came in quick succession and cemented his legacy. There was Nishant (1975), where he explored the abuse of power by feudal lords and the resilience of ordinary villagers. Next was Manthan (1976), which became India’s first crowdfunded feature film. Some 500,000 farmers paid two Indian rupees each to help tell the story of a milk cooperative and the power of grassroots collective action. Bhumika (1977) was a raw portrayal of a woman’s journey of love, ambition and self-discovery. Each film touched on the social and political realities of post-Independence India, painting portraits of marginalised communities with sensitivity and authenticity.

Aurora for more

Shyam Benegal: The Guardian of New Wave Cinema

by SOHINI CHATTOPADHYAY

Ankur is regarded as a landmark film in what is known as the Indian New Wave movement dated to the ’70s – the coming together of film professionals trained in the Film and Television Institute of India, Pune.

In that last light of day before it is all gone and the crickets have begun calling, a man hurries through paddy fields swollen with the rain that has fallen all day to a hovel that stands across his sturdy home, the lantern in his hand casting a luminous, almost painterly glow in the darkness. Inside the hovel, in the somewhat brighter light of the stove in the enclosed space, he deflates a bit, as if his eagerness has been caught out. “Who will make the tea?” he asks, looking suddenly embarrassed at the banality of his words. “Who will cook the food? The upkeep of the house – who will do that? Come to work from tomorrow,” he says. And the young woman he addresses can’t help smiling at the man’s artless plea.

Anant Nag, who plays the impulsive young man, is the son of the big landlord in the village and mostly called sarkar for the duration of his screen time here. It is one of Nag’s first films, he also debuted in a Kannada film called Sankalpa made around the same time. He worked on the stage before this. The young woman he hurries to, Lakshmi, is played by a debutante Shabana Azmi. The year is 1974. It is Shyam Benegal’s debut feature Ankur, based on a newspaper report that Benegal had read about the Telengana Movement of 1946-1951 in which peasants resisted the feudal extortion of landlords who owned obscenely large tracts of land.

The landlord’s young son reluctantly returns from the city – with a third-class degree – and is put to work looking after the estate by his domineering father. Sarkar drives a motorcar through the unpaved muddy roads of the estate and a tyre comes badly stuck in the mud. He listens to songs from the cinema on his Long Play (LP). The young man is remoulded a little by the changes he has seen in the city: he does not believe in caste he says, although we shall see that this is not as true as he thinks it is.

But he does make it a point to ask Lakshmi, the lower caste woman who serves him, to cook for him, eschewing the village priest’s offer to send him meals from his home. He is attracted to Lakshmi and enters into a relationship with her that cannot be called consensual, but he speaks with her with kindness. Her husband Kishtaiyya is a deaf-mute potter who has taken to drink, and sarkar assures her that he will take care of her. But he panics when he learns Lakshmi is pregnant with his child. The city-educated landlord wants to be different from his father but finds himself unable to be the man he thought he was, the old ways sucking him in like the slush on the ground slipping, tripping, tricking his beautiful motorcar. When his father, “the bade sarkar,” orders his young daughter-in-law to start living with the son, he abandons Lakshmi, pregnant with his child, and without a source of income. The young man’s guilt finds an outlet in Lakshmi’s deaf-mute husband Kistayya: at the film’s close, when he approaches the “sarkar” for a job, delighted that his Lakshmi will be a mother, the sarkar whips him. My reading is that Kistayya is well aware that he is unable to father a child.

The Wire for more

Benegal tribute | Long live Shyam Babu. You are a story well told

by ATUL TIWARI

Shabana Azmi, Anant Nag, Smita Patil, Nasiruddin Shah, Om Puri, Amrish Puri, Rajit Kapur and Irrfan Khan — there was the famous Benegal touch behind all of them.

The famous British film critic Derek Malcolm said, “Shyam Benegal’s films provided a huge marker for other young directors of what was once hopefully called the Indian parallel cinema.” Yet, Benegal himself used to say, “I do not know if there is such a thing as a new wave. Let me put it this way, some people now attempt to make films of their choice, different from the industry’s mould…. And now there is wide range of people, from one end of the scale to the other, who want to make their own kind of films.”

This humility, this self-effacing attitude was the hallmark of this great man.

His undisputed greatness was recognized with his first film itself. In 1974, when Benegal’s Ankur (The Seedling) sprouted, it brought a breath of fresh air with its bold and incisive social critique, and its agency against inequality and injustice born out of deep-rooted societal discriminations. The film, which captured this friction caused by caste-distinction, unequal gender relations, tension between modernity and ancient traditions, stands out both artistically and aesthetically. Ankur remains a ‘tool-kit’ — to which Benegal went back again and again.

Apart from many new values that Ankur brought to the world of Hindi cinema, it also brought a plethora of new actors, which included a trailblazer who has remained active as an actor and activist — Shabana Azmi.

A year later came Nishant, which in many ways was a sequel to Ankur. Here the similar theme of feudal exploitation of the rural poor –- especially women –- comes out even more brazenly, brutally, vividly. With two gifted ladies Shabana Azmi and Smita Patil in the film, which boasted of a hugely talented cast, Nishant actually brought a new dawn in Indian cinema. It went on to be India’s official entry in the competition section of Cannes Film Festival in 1976.

To complete an unintended trilogy Manthan arrived in 1976. The film dealt with the churnings in similar social conditions in a Gujarat village, but highlighted very different means employed to bring about change. It explored the ushering in of change through a co-operative society (Amul) for the milk producers of this impoverished region. These milk sellers had till then been exploited by the middlemen and big private companies who were milking these hapless men and women dry.

These films highlighted Shyam the social historian who as Benegal’s friend, critic and poet Anil Dharkar commented “looks at the mass experiences of history, through his films”.

Early days and the Nehruvian worldview

Benegal had been exposed to the world of visual images, art, painting, photography and films from the very beginning of his life. His father Shridhar Benegal had a small but well-endowed photography studio in Secunderabad cantonment, close to the city of Hyderabad. Painting was Shridhar Benegal’s other passion.

Shyam too was given an 8mm camera to play with, and taught the skills of developing a film and printing on photopaper. His friendship with the projectionist of the Garrison Cinema, in Secunderabad, gave the young Shyam access to world cinema – a la the protagonist in Cinema Paradiso.

Then Shyam went to study economics at Nizam College in the wonderfully charged atmosphere of those days, when as the nation was embracing independence the Nizam and his Razakars refused to align with free India. There were also the communists whose writ ran in the state at night, especially in the Telangana region. In some other parts of the Hyderabad state, the Hindu Mahasabha too had its hold.

It’s this churn that shaped the political sensibilities of the young economics graduate who saw the new India through the Fabian socialist, modernist, egalitarian point of view of the first Prime Minister Nehru. These values are well reflected in his cinema.

Women-centric films and the introduction of AR Rahman

In Bhumika (1977), based on actress Hansa Wadkar’s biography, Benegal chooses to reconstruct the past, harsh present and the make-believe film world in three different tonalities and hues. This artistic decision was made to make good use of the problem — of obtaining the supply of the rationed raw-stock in mid-seventies. Benegal decided to use the Orvo, Geva, Eastman-colour and black and white stock for different sections of the film. These different hues delineate the lead character Usha’s private, public and past persona very well.

Benegal’s two other films on performing public-women Sardari Begum (1996) and Zubeidaa (2001) are also in a league of their own. The use of music in all three is very evocative.

Zubeidaa saw the introduction of AR Rahman for the first time in a Benegal film – till then the inimitable music maestro Vanraj Bhatia had scored the music for his films. A few people did criticise Benegal for having drifted from the ‘parallel’ line towards the mainstream as he used two mainstream actors –- Rekha and Karishma Kapoor — and a popular music director in Zubeidaa.

‘A Gateway to film industry’

The Zubeidaa backlash was in some ways expected as he had only used trained but unknown new faces in his films till then. Indeed such had been his reputation that Benegal was given the moniker of ‘A Gateway to film industry’, in the manner of the famed ‘Gateway of India’ in Mumbai.

He had been responsible for giving countless new actresses and actors to the Indian cinema, a feat unmatched by anyone else in Bombay’s film world. These include Shabana Azmi, Anant Nag, Priya Tendulkar, Smita Patil, Nasiruddin Shah, Om Puri, Amrish Puri, Kulbhushan Kharbanda, Savita Bajaj, Nafisa Ali, Surekha Sikri, Rajeshwari Sachdev, Rajit Kapur, Irrfan Khan and at least a hundred others when he made Discovery of India.

Tryst with Comedy

The 1983 film Mandi marked a new chapter in Benegal’s oeuvre — comedy. Based on a story by Pakistani writer Ghulam Abbas, it was inspired by an actual incident. When Congressmen in Allahabad agitated to shift a red-light area from the centre of the city, someone said, “If you shift a brothel from the city, then the city would also shift itself to the bordello.” How one wishes that even an iota of this pragmatism was to be found in today’s duplicitous political leaders.

Coming back to the point of comedies, whenever Bengal took that route to tell a story, he was able to tickle the funny bone of his audiences. Apart from Mandi, Welcome to Sajjanpur (2008) and Well Done Abba (2009) served as good examples of this.

TV, The Discovery of India and his love for History

The New Indian Express for more

Shyam Benegal (1934-2024), who masterfully wielded cinema as an instrument of social change, passes away

FRONTLINE NEWS DESK

Legendary filmmaker, who made classics like Ankur and Bharat Ek Khoj, revolutionised Hindi cinema with social realism and powerful storytelling.

Shyam Benegal, who heralded a new era in Hindi cinema with the ‘parallel movement’ in the 1970s and 1980s with classics such as Ankur, Mandi and Manthan, died on Monday, December 23, after battling chronic kidney disease. He was 90.

The filmmaker, a star in the pantheon of Indian cinema’s great auteurs, died at Mumbai’s Wockhardt Hospital, where he was admitted in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU). “He passed away at 6.38 pm at Wockhardt Hospital Mumbai Central. He had been suffering from chronic kidney disease for several years, but it had gotten very bad. That’s the reason for his death,” his daughter Pia Benegal told media. He is survived by his daughter and wife, Nira Benegal.

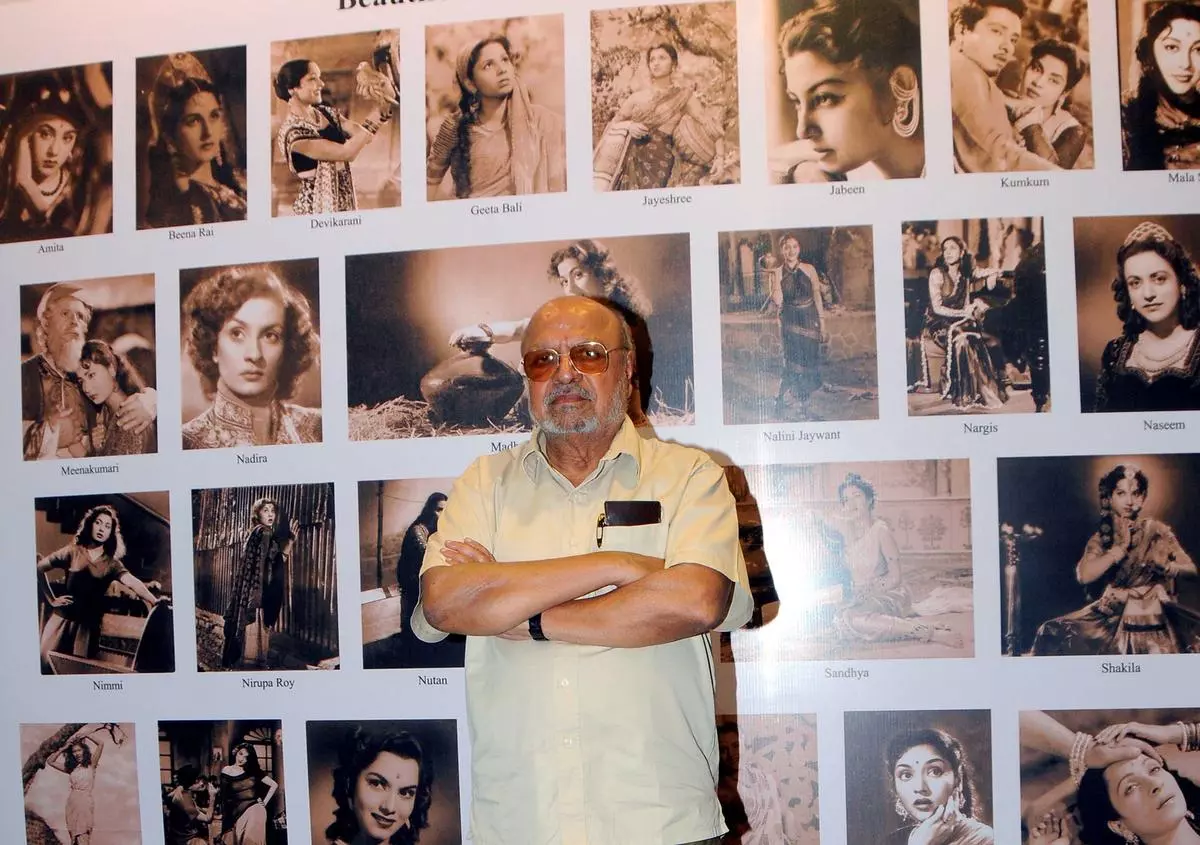

Just nine days ago, on his 90th birthday, actors who had worked with him through the decades gathered to wish him on the landmark day, almost as a last sayonara to the filmmaker who had given them perhaps the best roles of their careers. Among those who had gathered were Shabana Azmi, who made her debut with the powerful Ankur in 1973; Naseeruddin Shah, Rajit Kapoor, Kulbhushan Kharbanda, Divya Dutta, and Kunal Kapoor. That photograph of a smiling Benegal with his actors down the ages is his last in public.

Many worlds, many forms

In his prolific, almost seven-decade career, Benegal straddled diverse worlds, diverse mediums, and diverse issues, right from rural distress and feminist concerns to sharp satires and biopics. His oeuvre encompassed documentaries, films, and epic television shows, including Bharat Ek Khoj, an adaptation of Jawaharlal Nehru’s Discovery of India, and Samvidhaan, a 10-part show on the making of the Constitution.

And he wasn’t calling it quits anytime soon. “I’m working on two to three projects; they are all different from one another. It’s difficult to say which one I will make. They are all for the big screen,” Benegal said on the occasion of his 90th birthday. He also spoke of his frequent visits to the hospital and that he was on dialysis. “We all grow old. I don’t do anything great (on my birthday). It may be a special day, but I don’t celebrate it specifically. I cut a cake at the office with my team.” His films include Bhumika, Junoon, Suraj Ka Satvaan Ghoda, Mammo, Sardari Begum and Zubeidaa, most counted as classics in Hindi cinema.

His biopics include The Making of the Mahatma and Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose: The Forgotten Hero. The director’s most recent work was the 2023 biographical Mujib: The Making of a Nation. He was also keen to bring to life the story of Noor Inayat Khan, the secret WW II agent. That dream will sadly remain unfulfilled.

Benegal’s Manthan on Varghese Kurien’s milk cooperative movement in Anand, Gujarat, starring Smita Patil, Girish Karnad, and Naseeruddin Shah, was restored and screened at the Cannes Classics segment in the French Riviera town in May this year.

Tributes

Tributes to Shyam Babu, as he was known to friends and colleagues, who rewrote the rules of Indian movies, poured in. President Droupadi Murmu condoled the demise of Benegal and said his passing away marks the end of a glorious chapter of Indian cinema and television. Murmu said Benegal started a new kind of cinema and crafted several classics. “A veritable institution, he groomed many actors and artists. His extraordinary contribution was recognised in the form of numerous awards, including the Dadasaheb Phalke Award and Padma Bhushan. My condolences to the members of his family and his countless admirers,” the President said in a post on X.

The Congress condoled the passing of Benegal, with party chief Mallikarjun Kharge saying his tremendous contributions to the art form, marked by thought-provoking storytelling and a profound commitment to social issues, left an indelible mark.

Frontline for more