by REUT HARARI

Abstract: Who is allowed to practice medicine? This question recurred in different forms throughout Japan’s modern era, reflecting fundamental changes in how people provided and received medical care. This article explores one key issue that underlined this question: a persistent doctor shortage, whose causes and form changed over time—from the late wartime era, through the immediate postwar rehabilitation years, to the era of rapid economic growth. Rather than focusing on issues of policy, the article examines personal histories, revealing how shortages led to various doctor substitutes, some legitimate and some not, in a process whereby doctor care came to be seen as a basic right.

Who is allowed to practice medicine, and in what capacity? What is the relationship between medical licensing and skill? In postwar Japan, discussion around these questions was inextricably linked to what was often referred to as the doctor shortage problem (ishi busoku ????). During the final years of the Asia-Pacific War (1937–1945), the Japanese military enlisted an ever-growing number of doctors, creating shortages at home. To meet this demand, medical education grew shorter, and standards dropped. After Japan’s defeat, under the American occupation, medicine underwent demilitarization and broad reform, reshaping medical practices as well as the criteria for practicing. Yet, concomitantly, the population faced a potential humanitarian disaster as a result of the ongoing impact of the destruction of war. Every capable hand was needed to provide medical care, even at the price of turning a blind eye to the absence of formal accreditation. Only decades later, when Japan began to enjoy a culture of plenty, did medical quality—and the power of a license to ensure it—rise to public attention and become a matter for debate.

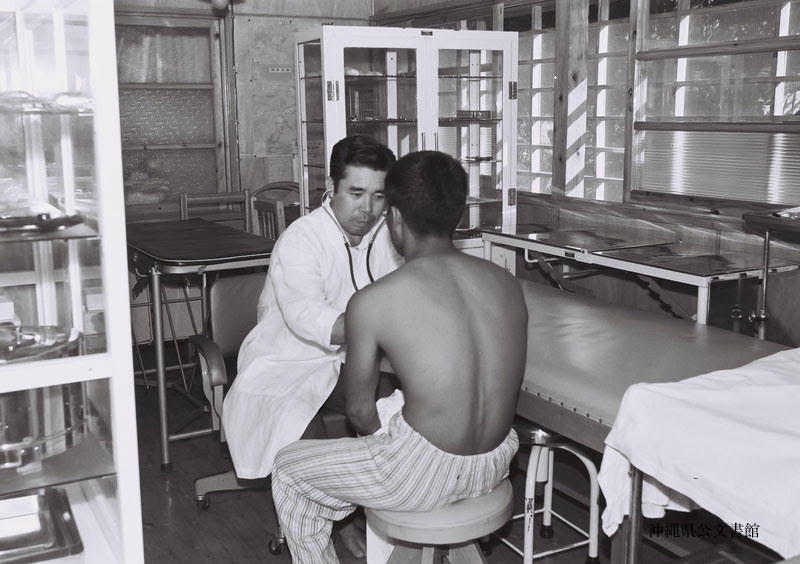

At the center of these debates were individuals who doctored the population without the title of doctor. I refer to this phenomenon as medical workarounds. During each historical stage—war, occupation, and reconstruction—medicine underwent reconfiguration, which included a redefinition of its professional boundaries. Change, however, took time, while the demand for medical services on the ground remained urgent. The gap between changes that would improve the future and current needs led to the emergence of workarounds—ways of practicing medicine beyond the official paths of training and licensing.

These non-doctors answered a genuine need, providing help to numerous people who had no other recourse and earning reputations as respectable professionals. In certain instances, particularly during the period of rapid economic growth, some referred to them as “quacks” or “charlatans” (nise isha ???) to discredit and belittle them, as they challenged the professional boundaries of the accredited medical system. There were also cases of non-doctors who indeed caused harm by offering substandard services under false pretenses or attempting treatments they had no skill to provide. Referring to non-doctors as quacks, however, obfuscates the broader significance and varied nature of these people and the services they provided. As the article reveals, the differences between the licensed and unlicensed could be blurry, with some non-doctors possessing equal or even superior skill when compared with licensed counterparts. And in Okinawa, non-doctors were also licensed.1 Examining the actions of this broad group within the framework of medical workarounds rather than quackery provides a better understanding of this largely overlooked history of medicine in action.

One reason this history has gone largely unnoticed is its unofficial nature. In most cases, non-doctors did not operate as an organized group within a formal, documented framework. Instead, their history appears in personal stories, which powerfully reveal lived experiences and daily realities of life that typically escape regulatory records. Accordingly, each section of the article focuses on the personal story of one individual, based on interviews and memoirs—rare sources, many of which are rapidly disappearing. For a significant period, the wartime generation refrained from sharing their life stories, and now, with the passage of time, fewer and fewer remain to do so.

APJJF for more