Archive for May, 2009

Weekend Edition

Friday, May 29th, 2009Worms and Liars

Friday, May 29th, 2009By B. R. Gowani

The Jewish TaNaKh says:

(the Bible too,

the Qur’an somewhat differs)

After creating the universe

In five days;

On the sixth day:

God created Adam and Eve.

And then came the Sabbath.

Or can it be that

God then slid into permanent coma

And hence the screwed up world?

Al Qaeda created/inspired many groups:

Most of them are busy

Blowing up people and things …

But where is Osama?

Resting? Or in a permanent coma?

Frequently since 2001 headlines read:

“US attack kills Taliban in great numbers” or

“Pakistan hands over Al Qaeda members to US”

Subsequently, often it is acknowledged:

Many of these were/are innocent civilians!

Notwithstanding the innocents,

The sheer numbers murdered should account for

Total number of Muslim militants …

Many times over.

So what is the true reality?

The recent bombings in Pakistan show

A proliferation of militants

How is that possible, given so many proclaimed deaths?

Do they multiply before dying,

Or are the US/Pak leaders lying?

Or is it …

New militants are born from the US bombs

and are propagating like vermin?

B. R. Gowani can be reached at brgowani@hotmail.com

A decade on, East Timor is still linked to Indonesia

Friday, May 29th, 2009East Timor ten years after the referendum

Hedda Haugen Askland and Thushara Dibley

A street vendor in Dili selling Indonesian books and other

products imported from Indonesia

Thushara Dibley

August this year marks ten years since the historic vote in East Timor for independence from Indonesia. In that time East Timor has become established as an independent nation whose leaders have cultivated a nationalism that emphasises East Timor’s Portuguese heritage and valorises the resistance against the Indonesian occupation. Nonetheless, as the contributors of this edition show, independent East Timor remains connected to Indonesia in diverse and intricate ways.

Not long after East Timor became independent, Inside Indonesia decided we would no longer run stories about East Timor, unless they dealt directly with the new country’s connection – historical or current – to Indonesia. East Timor was now an independent country, and we thought it would be an insult to treat domestic East Timorese affairs as if they were still ‘inside’ Indonesia. Ten years on, we’ve decided to devote an entire edition to the relations between the two countries, to look both at the legacies of the past occupation and at connections that continue in the present.

Inside Indonesia for more

Megaprojects and Militarization: A Perfect Storm in Mexico

Friday, May 29th, 2009Todd Miller

The 40-day blockade of the Trinidad mine in the Oaxacan community of San José del Progreso came to a sudden and violent halt on May 6. Mine representatives and municipal authorities called in a 700-strong police force that stormed into the community in anti-riot gear along with an arsenal of tear gas, dogs, assault rifles, and a helicopter.

The overwhelming show of force was in response to community residents’ demand that the Canadian company Fortuna Silver Mines immediately pack its bags and leave. The company is in the exploration phase of developing the Trinidad mine. The result was a brutal attack, with over 20 arrests and illegal searches of homes. Police seemed to be going after a heavily armed drug cartel, not a community protest.

This is one of the drug war’s dirty secrets: As Mexican security budgets inflate with U.S. aid – to combat the rising power of drug trafficking and organized crime – rights groups say these funds are increasingly being used to protect the interests of multinational corporations. According to a national network of human rights organizations known as the Red TDT, security forces are engaged in the systematic repression of activists opposed to megaprojects financed by foreign firms such as Fortuna Silver Mines.

NACLA for more

The Left-Wing Media Fallacy- Jeremy Bowen, The BBC, And Other National Treasures

Friday, May 29th, 2009By David Edwards

It is a mistake to imagine that media corporations are impervious to all complaints and criticism. In fact, senior editors and managers are only too happy to accept that their journalists tend to be ‘anti-American,’ ‘anti-Israel,’ ‘anti-Western,’ indeed utterly rotten with left-wing bias.

In June 2007, an internal BBC report revealed that Auntie Beeb had long been perpetrating high media crimes, including: “institutional left-wing bias” and “being anti-American”. (‘Lambasting for the “trendy Left-wing bias” of BBC bosses,’ Daily Mail, June 18, 2007)

Former BBC political editor, Andrew Marr, applied his forensic journalistic skills, noting that the BBC was comprised of “an abnormally large proportion of younger people, of people in ethnic minorities and almost certainly of gay people, compared with the population at large”. This, he deduced, “creates an innate liberal bias”. (Nicole Martin, ‘BBC viewers angered by its “innate liberal bias”,’ Daily Telegraph, June 19, 2007)

On the other hand, despite the fact that the media system is made up of corporations that are deeply dependent on corporate advertisers (for revenue) and official government sources (for subsidised news), other possibilities are unthinkable. If one were crazy enough, one might ask, for example:

‘Is it accurate to describe the corporate media as servile to concentrated power? Or, as a key component of the state-corporate system, is media propaganda best described as a form of self-service?’

Zmag for more

Two Funerals and a Wedding

Friday, May 29th, 2009The Battle of Swat, the Indian Elections and the End of the Sri Lankan Civil War

By NIRANJAN RAMAKRISHNAN

There were three significant happenings this week up and down the vertical axis of the Indian Subcontinent.

Up in the North, Pakistani troops battled the Taliban in Swat. As the week closed they had just begun the battle for Mingora, the capital town of the picturesque vale.

Meanwhile down South on a coastal strip along the Indian Ocean, the Sri Lankan Army was concluding what is being called Eelam War IV, the final chapter ending in the elimination of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), and the killing of its legendary chief, Prabhakaran. It marked the end of a government military operation that matched the LTTE’s own ruthlessness and savagery.

In the middle was India, electing its 15th parliament, fifty seven years since its first. The Congress party, which governed the last five years in a tenuous coalition, was returned to power with increased numbers, while its opponents on the nominal right and left were both shorn of seats.

It was Winston Churchill who remarked that the United States could usually be relied upon to do the right thing… after having tried everything else. The same remark might apply to Pakistan with this alteration, “after having secured promises of billions in additional aid”. Following several months of dilly-dallying — even an accommodation with the Taliban — essentially letting the outlaws run the judicial system in Swat, Pakistan finally moved. Whether nudged by world outrage at the YouTube video of a young lady in Swat being publicly whipped by Taliban goons, or whether as a result of the latest administration of the ancient American patent medicine for Pakistan (one part threat, four parts blandishment) the army appeared to shake off its post-Waziristan funk and move with dispatch and determination against the insurgents. Like the military operations in Sri Lanka, this has resulted in large numbers of refugees (1.4 million per one report) fleeing their homes to escape the fighting. The devastation of the fight for Mingora is yet to come. And there is something unseemly against an army being used against one’s own population, a fact likely to stick in many craws in the months and years to come. But as with Indira Gandhi and Bhindranwale, sometimes the biggest punishment is simply having to eat one’s own cooking.

Widespread celebration all over Sri Lanka greeted the Sri Lankan president’s announcement that the LTTE had been crushed, and that peace had returned to the island paradise (incidentally, the word ‘serendipity’ comes from an old name for Sri Lanka). The civil war there has continued for nearly 30 years. Lincoln concluded his in four. But that is as far as the analogy may be pushed. Compared to the complexities of the Lankan problem, the American Civil war was a piffle. Tamils, though a minority, make up over 25% of the population. They were for long part of the establishment until they were purged by the Sinhalese. Unlike blacks in the US, Tamils have inhabited Sri Lanka for over a millennium, some say even longer than the Sinhalese. And unlike the overt crime of slavery, in the US, Tamils in Sri Lanka have for fifty years been subject to a below-the-radar apartheid, punctuated by pogroms connived at by the Sinhalese establishment. The LTTE was a reaction to this, in the end an overreaction. But if the Tamil’s status in Sri Lanka is at all recognized widely and on its way to being addressed, Prabhakaran for all his crimes and follies deserves a due measure of credit. It is trite to invoke Lincoln’s words about binding the wounds, but it is no less true for that.

Like Sherlock Holmes’ curious incident of the dog in the night, the Indian elections were remarkable for what did not happen.

Counterpunch for more

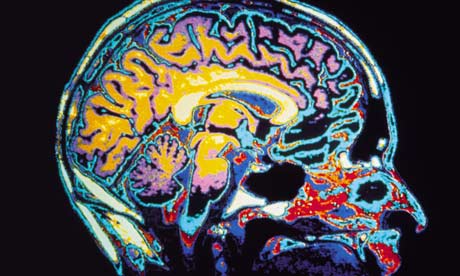

A neuroscience arms race could lead to guilt-free soldiers

Friday, May 29th, 2009The science of the brain is poised to play a major role in the wars of the future, according to Jonathan Moreno at Penn State University

Psychological onslaught: How do you make your enemy feel defeated? Photograph: Howard Sochurek/Corbis

Military strategists grasped the importance of the mind on the battlefield when people first crossed clubs. But advances in modern day neuroscience and pharmaceuticals could transform the way wars are fought in coming decades.

In a recent defence intelligence agency report, leading scientists were asked to cast their minds forward 20 years and describe how neuroscience might be used by the military. They described “pharmacological land mines”, performance boosting drugs and electronic devices that make it impossible to lie.

The issue has now been picked up by Jonathan Moreno, an expert on the ethics of neuroscience and national security, in a new series of video interviews at Penn State.

Moreno kicks off talking about psychological operations. How do you make your adversary feel defeated, and how does the brain contribute to the sense that you can win or have already lost?

So far so familiar. But later on in the interview, Moreno gets on to issues of interrogation and waterboarding; whether we want guilt-free soldiers, and the prospect of a neuroscience arms race.

Guardian for more

Kurdish singer Tara Jeff

Friday, May 29th, 2009Will China Save the World from Depression?

Thursday, May 28th, 2009By Walden Bello (Foreign Policy in Focus)

Will China be the “growth pole” that will snatch the world from the jaws of depression?

This question has become a favorite topic as the heroic American middle class consumer, weighed down by massive debt, ceases to be the key stimulus for global production.

Although China’s GDP growth rate fell to 6.1% in the first quarter — the lowest in almost a decade — optimists see “shoots of recovery” in a 30% surge in urban fixed-asset investment and a jump in industrial output in March. These indicators are proof, some say, that China’s stimulus program of $586 billion — which, in relation to GDP, is much larger proportionally than the Obama administration’s $787 billion package–is working.

Countryside as Launching Pad for Recovery?

With China’s export-oriented urban coastal areas suffering from the collapse of global demand, many inside and outside China are pinning their hopes for global recovery on the Chinese countryside. A significant portion of Beijing’s stimulus package is destined for infrastructure and social spending in the rural areas. The government is allocating 20 billion yuan ($3 billion) in subsidies to help rural residents buy televisions, refrigerators, and other electrical appliances.

But with export demand down, will this strategy of propping up rural demand work as an engine for the country’s massive industrial machine?

There are grounds for skepticism. For one, even when export demand was high, 75% of China’s industries were already plagued with overcapacity. Before the crisis, for instance, the automobile industry’s installed capacity was projected to turn out 100% more vehicles than could be absorbed by a growing market. In the last few years, overcapacity problems have resulted in the halving of the annual profit growth rate for all major enterprises.

There is another, greater problem with the strategy of making rural demand a substitute for export markets. Even if Beijing throws in another hundred billion dollars, the stimulus package is not likely to counteract in any significant way the depressive impact of a 25-year policy of sacrificing the countryside for export-oriented urban-based industrial growth. The implications for the global economy are considerable.

Subordinating Agriculture to Industry

Ironically, China’s ascent during the last 30 years began with the rural reforms Deng Xiaoping initiated in 1978. The peasants wanted an end to the Mao-era communes, and Deng and his reformers obliged them by introducing the “household-contract responsibility system.” Under this scheme, each household received a piece of land to farm. The household was allowed to retain what was left over of the produce after selling to the state a fixed proportion at a state-determined price, or by simply paying a tax in cash. The rest it could consume or sell on the market. These were the halcyon years of the peasantry. Rural income grew by over 15% a year on average, and rural poverty declined from 33% to 11% of the population.

This golden age of the peasantry came to an end, however, when the government adopted a strategy of coast-based, export-oriented industrialization premised on rapid integration into the global capitalist economy. This strategy, which was launched at the 12th National Party Congress in 1984, essentially built the urban industrial economy on “the shoulders of peasants,” as rural specialists Chen Guidi and Wu Chantao put it. The government pursued primitive capital accumulation mainly through policies that cut heavily into the peasant surplus.

The consequences of this urban-oriented industrial development strategy were stark. Peasant income, which had grown by 15.2% a year from 1978 to 1984, dropped to 2.8% a year from 1986 to 1991. Some recovery occurred in the early 1990s, but stagnation of rural income marked the latter part of the decade. In contrast, urban income, already higher than that of peasants in the mid-1980s, was on average six times the income of peasants by 2000.

The stagnation of rural income was caused by policies promoting rising costs of industrial inputs into agriculture, falling prices for agricultural products, and increased taxes, all of which combined to transfer income from the countryside to the city. But the main mechanism for the extraction of surplus from the peasantry was taxation. By 1991, central state agencies levied taxes on peasants for 149 agricultural products, but this proved to be but part of a much bigger bite, as the lower levels of government began to levy their own taxes, fees, and charges. Currently, the various tiers of rural government impose a total of 269 types of tax, along with all sorts of often arbitrarily imposed administrative charges.

Taxes and fees are not supposed to exceed 5% of a farmer’s income, but the actual amount is often much greater. Some Ministry of Agriculture surveys have reported that the peasant tax burden is 15% — three times the official national limit.

Expanded taxation would perhaps have been bearable had peasants experienced returns such as improved public health and education and more agricultural infrastructure. In the absence of such tangible benefits, the peasants saw their incomes as subsidizing what Chen and Wu describe as the “monstrous growth of the bureaucracy and the metastasizing number of officials” who seemed to have no other function than to extract more and more from them.

Aside from being subjected to higher input prices, lower prices for their goods, and more intensive taxation, peasants have borne the brunt of the urban-industrial focus of economic strategy in other ways. According to one report, “40 million peasants have been forced off their land to make way for roads, airports, dams, factories, and other public and private investments, with an additional two million to be displaced each year.” Other researchers cite a much higher figure of 70 million households, meaning that, calculating 4.5 persons per household, by 2004, land grabs have displaced as many as 315 million people.

Impact of Trade Liberalization

China’s commitment to eliminate agricultural quotas and reduce tariffs, made when it joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, may yet dwarf the impact of all the previous changes experienced by peasants. The cost of admission for China is proving to be huge and disproportionate. The government slashed the average agricultural tariff from 54 to 15.3%, compared with the world average of 62%, prompting the commerce minister to boast (or complain): “Not a single member in the WTO history has made such a huge cut [in tariffs] in such a short period of time.”

The WTO deal reflects China’s current priorities. If the government has chosen to put at risk large sections of its agriculture, such as soybeans and cotton, it has done so to open up or keep open global markets for its industrial exports. The social consequences of this trade-off are still to be fully felt, but the immediate effects have been alarming. In 2004, after years of being a net food exporter, China registered a deficit in its agricultural trade. Cotton imports skyrocketed from 11,300 tons in 2001 to 1.98 million tons in 2004, a 175-fold increase. Chinese sugarcane, soybean, and most of all, cotton farmers were devastated. In 2005, according to Oxfam Hong Kong, imports of cheap U.S. cotton resulted in a loss of $208 million in income for Chinese peasants, along with 720,000 jobs. Trade liberalization is also likely to have contributed to the dramatic slowdown in poverty reduction between 2000 and 2004.

Foreign Policy in Focus for more

The Ryukyus and the New, But Endangered, Languages of Japan

Thursday, May 28th, 2009By Fija Bairon, Matthias Brenzinger and Patrick Heinrich

Luchuan (Ryukyuan) languages are no longer Japanese dialects.

On 21 February 2009, the international mother language day, UNESCO launched the online version of its ‘Atlas of the world’s languages in danger’. This electronic version that will also be published as the third edition of the UNESCO Atlas in May 2009, now includes the Luchuan [Ryukyuan] languages of Japan (UNESCO 2009). ‘Luchuan’ is the Uchinaaguchi (Okinawan language) term for the Japanese ‘Ryukyu’. Likewise ‘Okinawa’ is ‘Uchinaa’ in Uchinaaguchi. Well taken, UNESCO recognizes six languages of the Luchu Islands [Ryukyu Islands] of which two are severely endangered, Yaeyama and Yonaguni, and four are classified as definitely endangered, Amami, Kunigami, Uchinaa [Okinawa] and Miyako (see UNESCO 2003 for assessing language vitality and endangerment).

Through publication of the atlas, UNESCO recognizes the linguistic diversity in present-day Japan and, by that, challenges the long-standing misconception of a monolingual Japanese nation state that has its roots in the linguistic and colonizing policies of the Meiji period. The formation of a Japanese nation state with one unifying language triggered the assimilation of regional varieties (hogen) under the newly created standard ‘national language’ (kokugo) all over the country (Carroll 2001). What is more, through these processes, distinct languages were downgraded to hogen, i.e. mere ‘dialects’ in accordance with the dominant national ideology (Fija & Heinrich 2007).

The entire group of the Luchuan languages – linguistic relatives of the otherwise isolated Japanese language – is about to disappear. These languages are being replaced by standard Japanese (hyojungo or kyotsugo) as a result of the Japanization of the Luchuan Islands, which started with the Japanese annexation of these islands in 1872 and was more purposefully carried out after the establishment of Okinawa Prefecture in 1879. In public schools, Luchuan children were educated to become Japanese and they were no longer allowed to speak their own language at schools following the ‘Ordinance of dialect regulation’ (hogen torishimari-rei) in 1907 (ODJKJ 1983, vol. III: 443-444). Spreading Standard Japanese was a key measure for transforming Luchu Islanders into Japanese nationals and for concealing the fact that Japanese was multilingual and multicultural (Heinrich 2004).

The US occupation of Uchinaa after World War II, which – at least formally – ended in 1972, marks the final stage in the fading of the Luchuan languages. In their attempts to separate Uchinaa from mainland Japan, Americans emphasized the distinctiveness of the Luchuan languages and cultures and encouraged their development. This US policy of dividing Luchuan from Japan, however, backfired and gave rise to a Luchuan Japanization movement. Today, even the remaining – mainly elderly – Luchuan language speakers generally refer to their languages as hogen, i.e. Japanese ‘dialects’, accepting in so doing the downgrading of their heritage languages for the assumed sake of national unity.

In support of the UNESCO approach, Sakiyama Osamu, professor emeritus of linguistics at the National Museum of Ethnology, stated that “a dialect should be treated as an independent language if its speakers have a distinct culture” (Kunisue 2009). However, linguistic studies also prove that these speech forms should be treated as languages in their own right (e.g. Miyara 2008), distinct both from Japanese as well as from one another. According to results employing the lexicostatistics method (Hattori 1954), the Luchuan languages share only between 59 and 68 percent cognates with Tokyo Japanese. These figures are lower than those between German and English. Scholars, as well as speakers, agree that there is no mutual intelligibility between these languages (Matsumori 1995). Thus calling them hogen (dialects of Japanese) may satisfy national demands of obedience but is problematic on linguistic and historical grounds.

…

Figure 1: Who do you address in local language? (448 consultants)

This chart reveals different degrees of language vitality, with the local language being most widely used in Yonaguni and Miyako. Yonaguni stands out because the local language is widely used in the neighbourhood, due to the Gemeinschaft (community) character of an isolated island with 1.600 inhabitants. Also worthy of notice is the frequent local language use among work colleagues, which is largely due to the lack of development of the secondary and tertiary economic sector in Yonaguni. Note, however, that the local language in Yonaguni is just as rarely used towards children as elsewhere. As a matter of fact, the restraint on use of local language towards children is the most consistent result across the five speech communities of Amami, Uchinaa, Miyako, Yaeyama and Yonaguni. (The sixth Luchuan language according to the UNESCO atlas, i.e. Kunigami, was at that time unfortunately not recognized as an independent language by Heinrich). On the lower end of language vitality, we find the Yaeyama language. Since endangered languages are always spoken in multilingual communities, specific domains of local language use must be maintained to secure their continued use. The most crucial domains for local language are the family and the local neighbourhood (shima or chima in the Luchuan languages, hence the term shimakutuba, ‘community language’). On the basis of the results presented in Figure 1, we see that the prospects for language maintenance are, at present, most favourable on Miyako Island. For more detailed discussions on language shift in the Luchu islands see Heinrich and Matsuo (2009).