by VELI MBELE

PHOTO/Getty Images

PHOTO/Getty Images

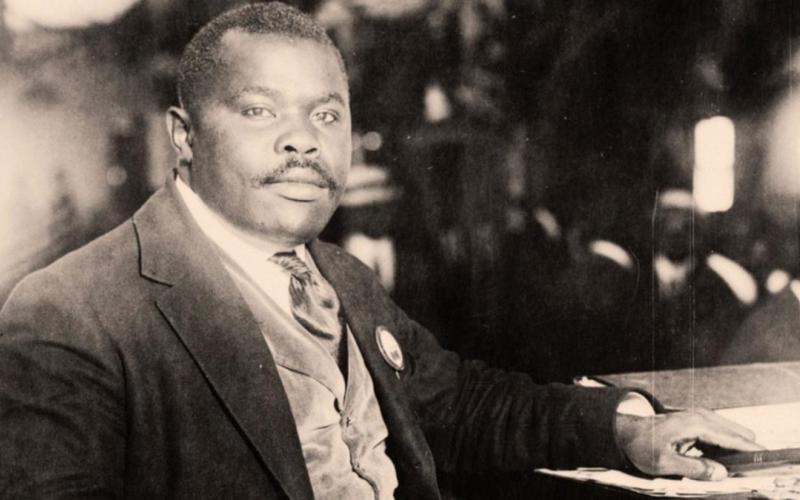

This paper deals with the meaning of Mwalimu Marcus Garvey and the Afrikan Revolution in the 21st century. Mwalimu Garvey is without doubt one of the most important figures of the Afrikan Revolution in the last 50 years and today, more than 70 years after his passing, his mission of total and unapologetic independence for the Black race, remains unfinished.

In order to argue this conclusion, we will reflect on critical moments in Black radical resistance that occurred during the month of August, provide a biographical sketch of who Garvey was, what his contribution was to the upliftment of the Black race, reflect on the challenges he encountered, what is his legacy and what are the implications of his work for the advancement of the Afrikan Revolution today.

1. Opening remarks

Egameni ledelakufa, Inkosi uMpolekeng Jantjie. Camagu!

Egameni ledelakufa, Inkosi uGalemidiwe Galeshewe. Camagu!

Egameni ledelakufa, Inkosi uToto Mokgolowe. Camagu!

Egameni ledeluka, uPhakamile Mabija. Camagu!

Egameni ledekafuka, uMmereki Morebudi. Camagu!

Egameni ledelakufa, uHutse Segolodi. Camagu!

Egameni ledelakufa, uAndries Tatane. Camagu!

Egameni ledelakufa, uNqobile Nzuza. Camagu!

Egameni lomfowethu, uJan Rivombo. Camagu!

Egameni ledelakufa,uSikhosiphi Rhadebe. Camagu!

Egameni likadedawethu, uAlem Dechasa. Camagu!

Egameni ledelakufa, uMgcineni Noki. Camagu!

Egameni lomfowethu, uMatlhomola Mosweu. Camagu!

Emagameni abodadebethu nabafowethu abashona eLife Esidemini. Camagu!

Egameni likaKumkanikazi uMam’uZondeni Sobukwe. Camagu!

Camagwini maAfrika!

We invoke these sacred names for a number of reasons. One, to remind us that, as Black people, we have a unique, complex, profoundly traumatic and continuing history that is not comparable to the histories of other races. Two, to remind us not to forget about the gratuitous and unprovoked violence that continues to be unleashed upon our Black bodies (even by our own kind).

And three, to never forget that we live in an era wherein there are some, (both within and outside our race), who would prefer that we be docile, apologetic, acquiesce, equivocate and even be untruthful, in how we reflect on our history and the place we now occupy in the world today, as Black people.

In what is regarded as mainstream public discourse, the general inclination is to try as much as possible to avoid topics or issues that directly affect Black people. And if such discourses do happen, the dominant approach is to use language that is analytically superficial, obfuscates the actual peculiarities that come with having a Black skin or tries as much as possible not to offend the architects and beneficiaries of Black suffering.

For instance, instead of talking about Black people, we seem more comfortable with soporific formulations such as “historically-disadvantaged”, “people from working class backgrounds” or “the poorest of the poor”. Essentially, we tend to prefer language that numbs the consciousness of Black people, instead of awakening it.

But why do we the Black people of today speak with such trepidation? There are a number of reasons for our nervousness. In explaining this form of self-censure, Frank Wilderson, observes that:

“…there is a way in which all Black speech is always coerced speech, in that you’re always in what Saidiya Hartman would call a context of slavery: anything that you say, you always have to think, ‘what are the consequences of me speaking my mind going to be?’”

Bantu Biko situationalises this point when he observes that:

“There is in South Africa an over-riding idea to move towards ‘comfortable’ politics, between leaders. And they hold discussions among themselves about this. Comfortable politics in the sense that we must move at a pace that doesn’t rock the boat. In other words people are shaped by the system even in their consideration of approaches against the system.”

He goes on to say:

“Not shaped in the sense of working out meaningful strategies, but shaped in the sense of working out an approach that won’t lead them into any confrontation with the system. So they tend to accommodate the system, to censure themselves, in a much stronger way than the system would probably censure them.”

Pambazuka for more