By NICHOLAS CANNARIATO

Dostoevsky, Hedayat, and formless rage

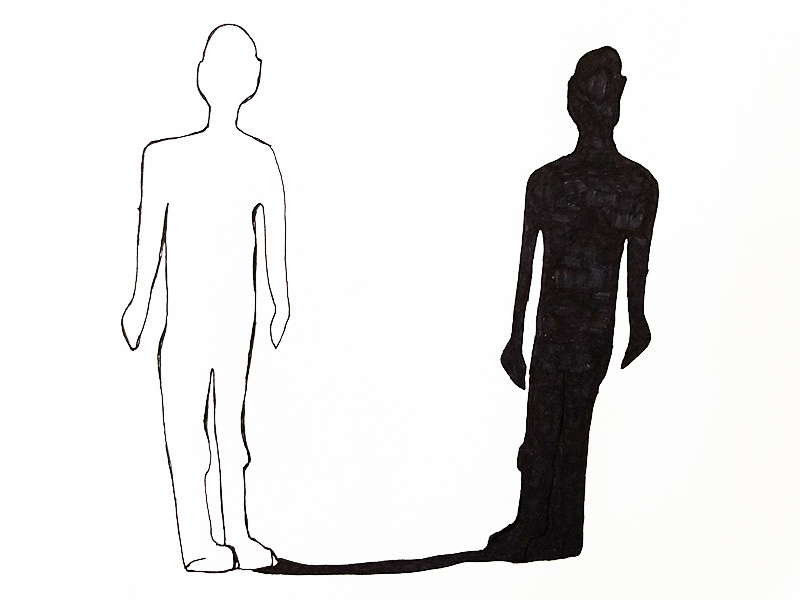

When revolt has no object, it turns on itself, opposing all imagined foes in wanton destruction of imagined barriers. Most apparently since the advent of Romanticism in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, revolt has often been focused on an object considered in more personal terms — the introspective rebel pitched against disinterested systems and in search of a soul divested of the stain of acquisition, the taint of the tangible. Yet, sometimes, all the rebel finds is empty space where identity used to dwell. And this is where we find ourselves in the West today, with open, democratic societies in the grip of revolt against rationalism and its accompanying pluralism.

Pankaj Mishra, in Age of Anger, asserts that Rousseau, a scion of Enlightenment thinking and one of its chief antagonists, saw the danger of shunting the religious, the provincial, and the irrational to the margins and the shadows. Rousseau asserted, after all, that social injustice originates not with the individual but with the existence of institutions. Despite this warning, more repressive forms of nationalism took shape and grew ominously over the next two centuries, culminating in Nazi and Soviet forms of totalitarianism.

And the persistence of pathological nationalism is undeniable. Whether it’s the debased atavism of so many Trump supporters or the rancid parochialism of so many Brexiters, resentment and entitlement still produce superfluous-feeling individuals tilted against the rational state apparatus that denies (or at least complicates) their nationalistic or ethnic sense of identity. But that rage just might have a deeper source than mere politics. Two of the books that profoundly reveal and explore the formless rage that precedes revolt are Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground and Sadegh Hedayat’s The Blind Owl.

Mishra, again in Age of Anger, recounts how Dostoevsky visited the Crystal Palace at the International Exhibition in London in 1862. Lamenting the worship of rationalism and materialism on display, he reflected on how, “you become aware of a colossal idea; you sense that here something has been achieved, that here is victory and triumph. You even begin vaguely to fear something . . . Must you accept this as the final truth and forever hold your peace? It is all so solemn, triumphant, and proud that you gasp for breath.” This is the damned seed that blooms into the angst of the the Underground Man in Notes from Underground, which would be published two years after that fateful trip. Mishra rightly observes that the rationalist/utilitarian ethic celebrated at the London exhibition prefigures the distrust of such an ethic pervasive in Dostoevsky’s subsequent major novels.

The Smart Set for more