THE CONVERSATION & DR. LORI MARINO

Hanako, a female Asian elephant, lived in a tiny concrete enclosure at Japan’s Inokashira Park Zoo for more than 60 years, often in chains, with no stimulation. In the wild, elephants live in herds, with close family ties. Hanako was solitary for the last decade of her life.

Kiska, a young female orca, was captured in 1978 off the Iceland coast and taken to Marineland Canada, an aquarium and amusement park. Orcas are social animals that live in family pods with up to 40 members, but Kiska has lived alone in a small tank since 2011. Each of her five calves died. To combat stress and boredom, she swims in slow, endless circles and has gnawed her teeth to the pulp on her concrete pool.

Unfortunately, these are common conditions for many large, captive mammals in the “entertainment” industry. In decades of studying the brains of humans, African elephants, humpback whales and other large mammals, I’ve noted the organ’s great sensitivity to the environment, including serious impacts on its structure and function from living in captivity.

Affecting health and altering behavior

It is easy to observe the overall health and psychological consequences of life in captivity for these animals. Many captive elephants suffer from arthritis, obesity or skin problems. Both elephants and orcas often have severe dental problems. Captive orcas are plagued by pneumonia, kidney disease, gastrointestinal illnesses and infections.

Many animals try to cope with captivity by adopting abnormal behaviors. Some develop “stereotypies,” which are repetitive, purposeless habits such as constantly bobbing their heads, swaying incessantly or chewing on the bars of their cages. Others, especially big cats, pace their enclosures. Elephants rub or break their tusks.

Changing brain structure

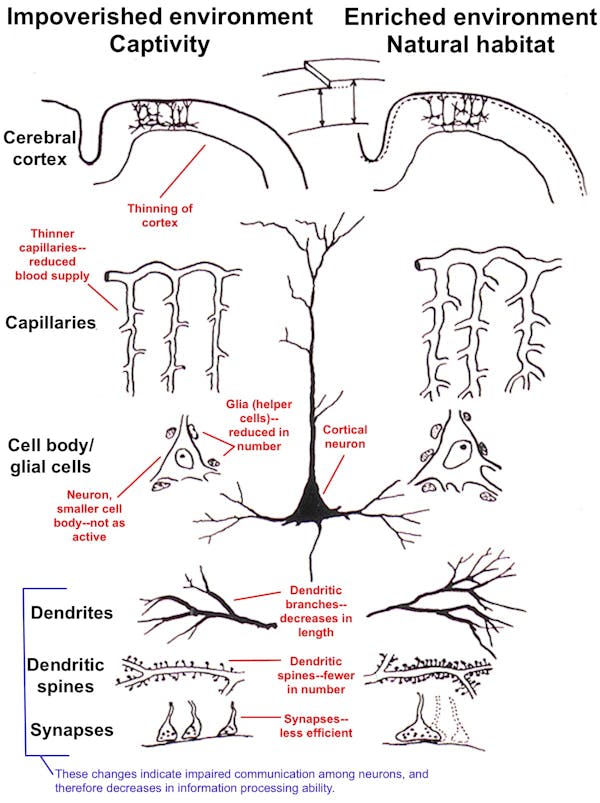

Neuroscientific research indicates that living in an impoverished, stressful captive environment physically damages the brain. These changes have been documented in many species, including rodents, rabbits, cats and humans.

Although researchers have directly studied some animal brains, most of what we know comes from observing animal behavior, analyzing stress hormone levels in the blood and applying knowledge gained from a half-century of neuroscience research. Laboratory research also suggests that mammals in a zoo or aquarium have compromised brain function.

The Conversation for more