by SOPHUS HELLE

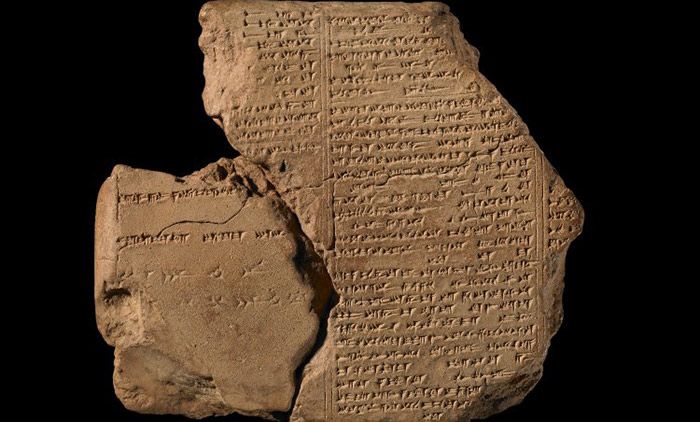

Part of a Neo-Assyrian clay tablet containing three columns of cuneiform inscription from tablet 6 of The Epic of Gilgamesh. PHOTO/the Trustees of the British Museum.

The Epic of Gilgamesh is a Babylonian poem composed in ancient Iraq, millennia before Homer. It tells the story of Gilgamesh, king of the city of Uruk. To curb his restless and destructive energy, the gods create a friend for him, Enkidu, who grows up among the animals of the steppe. When Gilgamesh hears about this wild man, he orders that a woman named Shamhat be brought out to find him. Shamhat seduces Enkidu, and the two make love for six days and seven nights, transforming Enkidu from beast to man. His strength is diminished, but his intellect is expanded, and he becomes able to think and speak like a human being. Shamhat and Enkidu travel together to a camp of shepherds, where Enkidu learns the ways of humanity. Eventually, Enkidu goes to Uruk to confront Gilgamesh’s abuse of power, and the two heroes wrestle with one another, only to form a passionate friendship.

This, at least, is one version of Gilgamesh’s beginning, but in fact the epic went through a number of different editions. It began as a cycle of stories in the Sumerian language, which were then collected and translated into a single epic in the Akkadian language. The earliest version of the epic was written in a dialect called Old Babylonian, and this version was later revised and updated to create another version, in the Standard Babylonian dialect, which is the one that most readers will encounter today.

Not only does Gilgamesh exist in a number of different versions, each version is in turn made up of many different fragments. There is no single manuscript that carries the entire story from beginning to end. Rather, Gilgamesh has to be recreated from hundreds of clay tablets that have become fragmentary over millennia. The story comes to us as a tapestry of shards, pieced together by philologists to create a roughly coherent narrative (about four-fifths of the text have been recovered). The fragmentary state of the epic also means that it is constantly being updated, as archaeological excavations – or, all too often, illegal lootings – bring new tablets to light, making us reconsider our understanding of the text. Despite being more than 4,000 years old, the text remains in flux, changing and expanding with each new finding.

Aeon for more