Chris Christie noticed a piece in the New York Times – that’s how it all started. The New Jersey governor had dropped out of the presidential race in February 2016 and thrown what support he had behind Donald Trump. In late April, he saw the article. It described meetings between representatives of the remaining candidates still in the race – Trump, John Kasich, Ted Cruz, Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders – and the Obama White House. Anyone who still had any kind of shot at becoming president of the United States apparently needed to start preparing to run the federal government. The guy Trump sent to the meeting was, in Christie’s estimation, comically underqualified. Christie called up Trump’s campaign manager, Corey Lewandowski, to ask why this critical job had not been handed to someone who actually knew something about government. “We don’t have anyone,” said Lewandowski.

Christie volunteered himself for the job: head of the Donald Trump presidential transition team. “It’s the next best thing to being president,” he told friends. “You get to plan the presidency.” He went to see Trump about it. Trump said he didn’t want a presidential transition team. Why did anyone need to plan anything before he actually became president? It’s legally required, said Christie. Trump asked where the money was going to come from to pay for the transition team. Christie explained that Trump could either pay for it himself or take it out of campaign funds. Trump didn’t want to pay for it himself. He didn’t want to take it out of campaign funds, either, but he agreed, grudgingly, that Christie should go ahead and raise a separate fund to pay for his transition team. “But not too much!” he said.

And so Christie set out to prepare for the unlikely event that Donald Trump would one day be elected president of the United States. Not everyone in Trump’s campaign was happy to see him on the job. In June, Christie received a call from Trump adviser Paul Manafort. “The kid is paranoid about you,” Manafort said. The kid was Jared Kushner, Trump’s son-in-law. Back in 2005, when he was US attorney for New Jersey, Christie had prosecuted and jailed Kushner’s father, Charles, for tax fraud. Christie’s investigation revealed, in the bargain, that Charles Kushner had hired a prostitute to seduce his brother-in-law, whom he suspected of cooperating with Christie, videotaped the sexual encounter and sent the tape to his sister. The Kushners apparently took their grudges seriously, and Christie sensed that Jared still harboured one against him. On the other hand, Trump, whom Christie considered almost a friend, could not have cared less.

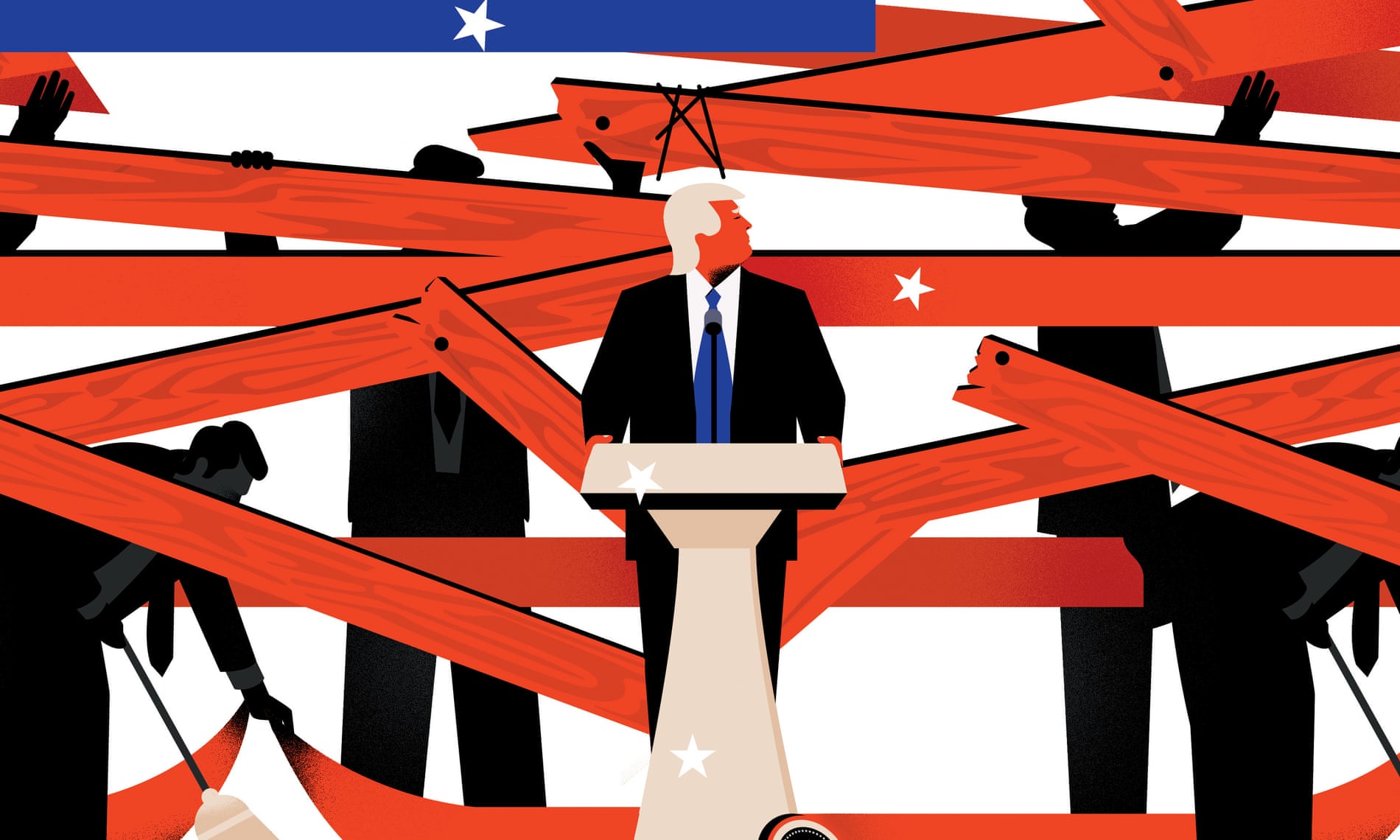

Christie viewed Kushner as one of those people who thinks that, because he is rich, he must also be smart. Still, he had a certain cunning about him. And Christie soon found himself reporting everything he did to prepare for a Trump administration to an “executive committee”. The committee consisted of Kushner, Ivanka Trump, Donald Trump Jr, Eric Trump, Manafort, Steve Mnuchin and Jeff Sessions. “I’m kind of like the church elder who double-counts the collection plate every Sunday for the pastor,” said Sessions, who appeared uncomfortable with the entire situation. The elder’s job became more complicated in July 2016, when Trump was formally named the Republican nominee. The transition team now moved into an office in downtown Washington DC, and went looking for people to occupy the top 500 jobs in the federal government. They needed to fill all the cabinet positions, of course, but also a whole bunch of others that no one in the Trump campaign even knew existed. It is not obvious how you find the next secretary of state, much less the next secretary of transportation – never mind who should sit on the board of trustees of the Barry Goldwater Scholarship and Excellence in Education Foundation.

The Guardian for more