by BENJAMIN KUNKEL

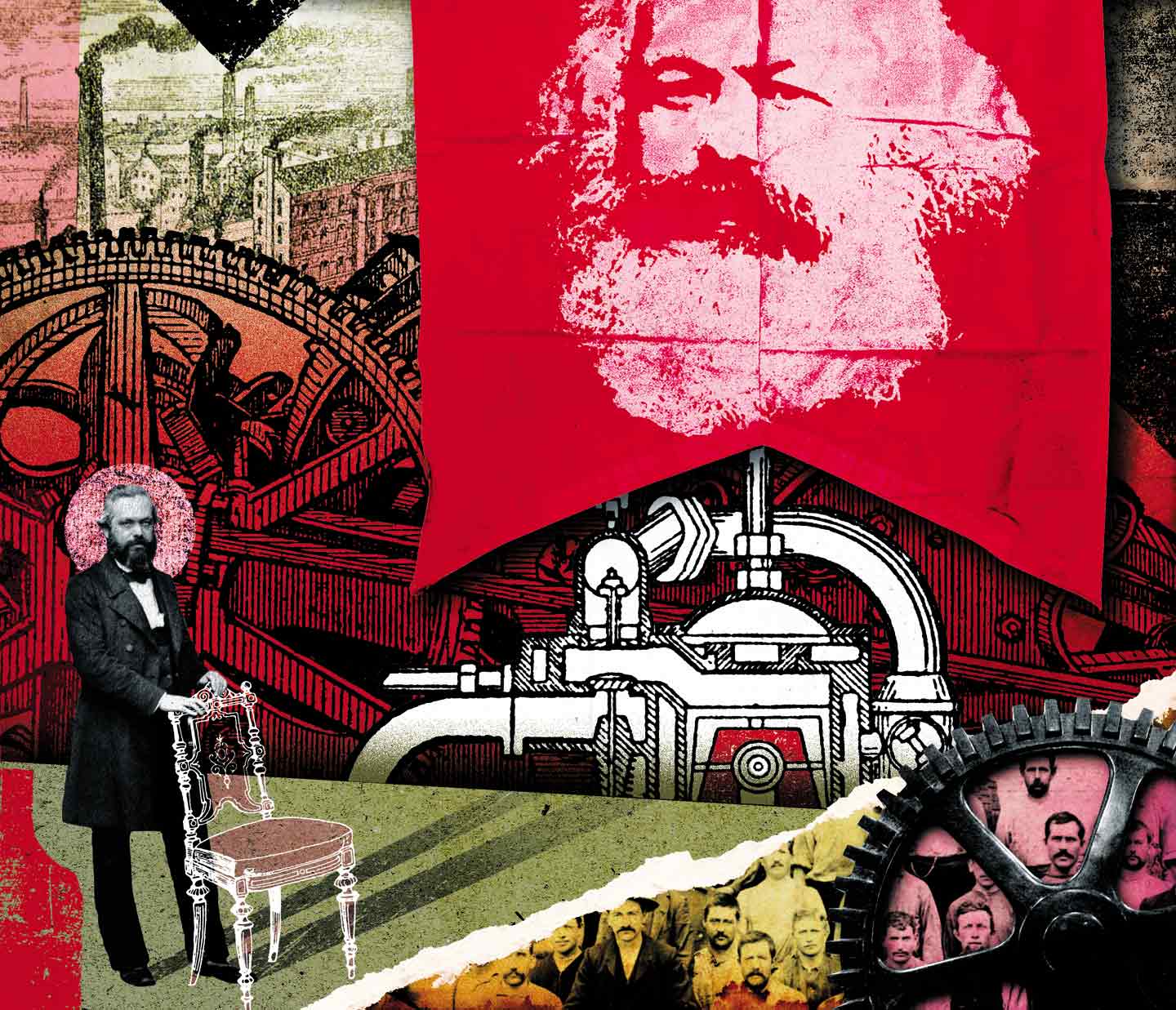

ILLUSTRATION/Tim Robinson

ILLUSTRATION/Tim Robinson

He may have lived a 19th-century life, but his ideas keep coming back with a vengeance

The many biographies of Karl Marx bring out a basic paradox in Marxism. Biographies are typically narratives of the lives of important figures who loom large against the backdrop of history. Yet Marxism, or “the materialist conception of history,” as the young Marx and his friend and collaborator Friedrich Engels called it, warned from the start against reading the past as the affair of solitary individuals rather than antagonistic classes. In particular, they argued that abstract ideas grew out of material circumstances instead of the other way around—and yet what secular ideology or political tradition emphasizes the special contribution of a lone thinker more than Marxism?

Marx himself would have been sensitive to this paradox. Of the half-dozen most important books in his bookish youth, one was a biography that downplayed the importance of a famous individual by the name of Jesus of Nazareth. David Strauss’s Life of Jesus was published in 1835, when Marx was in his late teens. Strauss didn’t deny the validity of Jesus’s teachings or question his historical existence; his book scandalized or, as in the case of Marx and Engels, excited German readers by arguing that the events of the Gospels weren’t factual occurrences but myths, collectively dreamed up by early Christians many years after Christ. Bruno Bauer, Marx’s mentor when he was working on his dissertation in Berlin, went further and declared Jesus an outright invention of the Gospel writers. The point was not, however, to undermine the “absolute idea” (in Bauer’s Hegelian vocabulary) of Christianity; it was to establish “human self-consciousness as the highest divinity,” as Marx (borrowing another Hegelian term) summarized the argument. Sacred truths were to be recognized as collaborative human artifacts, without necessarily forfeiting their truth in the process.

…

Marx died on March 14, 1883, from a hemorrhaged ulcer on the lung. He had survived his wife Jenny and also, heartbreakingly, his daughter Jenny, the eldest and best-loved of his children. The steady diet of grief administered across Marx’s life by the deaths of siblings and offspring may explain the mixture of steeliness (he could hardly pause to mourn) and compassion (he could hardly cease to mourn) characteristic of him as a thinker and a person. At Marx’s funeral, Engels gave a graveside speech to the 10 people present: “His name will endure through the ages, and so also will his work.” Stedman Jones refrains from quoting this forecast, which looks to have been correct.

…

The Communist Manifesto, as it came to be known, declares that human history to date is the history of class struggles, which end “either in a revolutionary reconstitution of society at large, or in the common ruin of the contending classes” and foresees that, after a succession of ever-greater economic crises and “the organization of the proletariat into a class, and consequently a political party,” bourgeois society will be made to yield to communism, in which “the free development of each is the condition of the free development of all.”

Arguably the most famous pamphlet ever written and the most important piece of universal literature since the Quran, the Manifesto had been all but forgotten a year after its publication, when the revolutionary mood ebbed away. The month after it first appeared, Marx, under suspicion— incorrectly, it seems—of using an inheritance from his mother to fund insurrection, was ordered to leave Belgium.

The Nation for more