by GREG WALDMANN

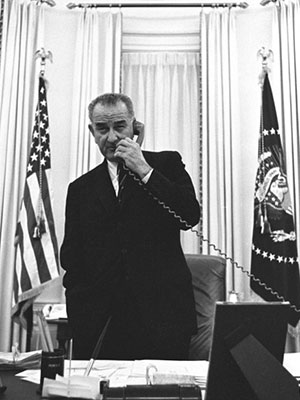

US president Lyndon B. Johnson (1908-1973)

US president Lyndon B. Johnson (1908-1973)

All The Way, HBO’s new movie about the passage and aftermath of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, is a messy and curiously double-minded affair. Like Selma, it wants to show that the shopworn narrative of white men grappling with fate in smoky rooms was never the whole story. But All The Waydoesn’t give Martin Luther King’s movement enough screen time to live again as the complex entity it was. Instead it’s portrayed as one of the many blocks Johnson has to shift around to secure passage of the bill.

But if All the Way reduces itself to the story of Johnson’s break with Southern whites then, however unintentionally, it does succeed in making one point very clearly: Nostalgia for the Johnson presidency is misplaced, thanks to forces set in motion by the man himself.

Obama’s second term has been rife with this species of nostalgia, which began with two precipitous events: the publication of the long-awaited fourth volume of Robert Caro’s biography of Johnson, and the dawning realization that if Barack Obama was elected to a second term the Republicans in Congress would block every single initiative he put before them. Historical comparisons are catnip to Washington’s paid thinkers, and a cottage industry of Johnson think-pieces bloomed. The less astute columnists built specious musings out of anecdotal accounts of disaffection between Obama and Congress. They wondered if the President was too remote or too partisan. “Washington is thick with stories about Obama’s insularity and distance,” wrote Richard Cohen, who fumed because “Obama cannot or will not indulge in the sort of face-to-face politicking that Johnson so favored.” What we needed, these pundits reasoned, was a president who could sweet-talk and brow-beat the Senate into moving mountains. But it would have been more accurate to blame Johnson than to praise him: As Robert Caro himself said at the time, Barack Obama is Lyndon Johnson’s legacy. Caro was referring to the man himself, but the statement is just as true if you apply it to the era.

The Civil Rights Act was languishing in Senatorial purgatory when Johnson took office. As Majority Leader, Johnson shepherded a civil rights bill to passage in 1957, but it had been watered down to near-meaninglessness. This time, he told Richard Goodwin, “I’m not going to bend an inch. In the Senate I did the best I could. But I had to be careful . . . But I always vowed that if I ever had the power I’d make sure every Negro had the same chance as every white man. Now I have it. And I’m going to use it.” Spurred on by the civil rights movement, harnessing its energy, he outflanked the South and secured the bill’s passage with an alliance of Republicans and liberal Democrats.

And then the South began drifting out of the Democratic party. Johnson fended off a nomination challenge from the segregationist governor of Alabama, George Wallace, weathered a walkout by some Southern delegates at the convention, and lost only six of 50 states to Republican Barry Goldwater in the general. Excepting Goldwater’s home state of Arizona, they were all in the South. This paved the way for Nixon’s “southern strategy” in 1968, with its barely-concealed racial overtones. Much of the region went for Wallace’s third-party run in 1968, but it was coming into the fold — Nixon won it all in 1972.

The Smart Set for more