by JOELLE ROLLO-KOSTER

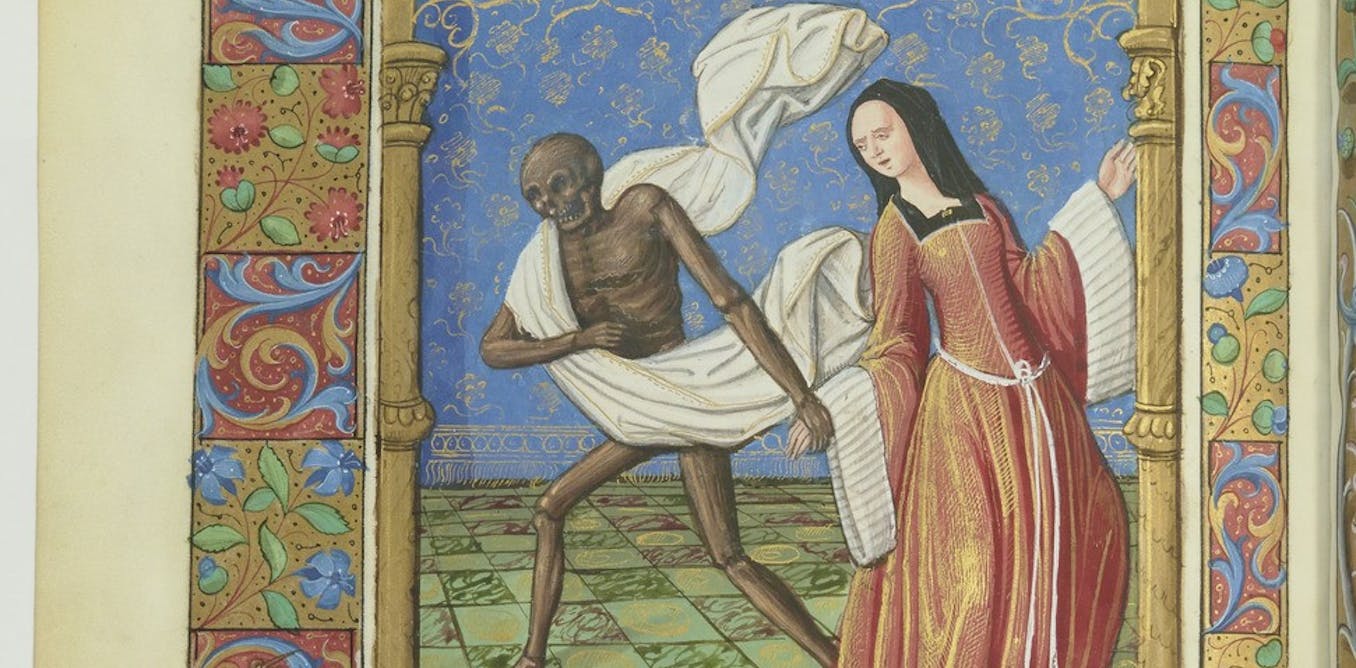

In medieval Europe, views of women could often be summed up in two words: sinner or saint.

As a historian of the Middle Ages, I teach a course entitled Between Eve and Mary: the two biblical figures who sum up this binary view of half of humanity. In the Bible’s telling, Eve got humans expelled from the Garden of Eden, unable to resist biting into the forbidden fruit. Mary, meanwhile, conceived the Son of God without human intercourse.

Either way, they’re daunting models – and either way, patriarchy considered women in need of protection and control. But how can we know what medieval women thought? Did they really accept this vision of themselves?

I do not believe that we can totally understand someone who lived and died hundreds of years ago. However, we can try to somewhat reconstruct their frame of mind with the resources we have available.

Analysis of the world, from experts

Few documents that survive from medieval Europe were written by women or even dictated by women. Those that do are often formulaic, full of legal and religious language. Yet the wills and censuses that survive, and which I study, open a window into their lives and minds, even if not produced by women’s hands. These documents suggest that medieval women had at least some form of empowerment to define their lives – and deaths.

A centuries-old census

In 1371, the city of Avignon, in present-day France, organized a census. The resulting document is ripe with the names of more than 3,820 heads of household. Of these, 563 were female – women who were in charge of their own household and did not shy away from declaring it publicly.

These were not women of high social status but individuals scarcely remembered by history, who left only traces in these administrative documents. One-fifth of them declared an occupation, including both single and married women: from unskilled laborer or handmaid to innkeeper, bookseller or stonecutter.

Nearly 50% of the women declared a place of origin. The majority came from around Avignon and other parts of southern France, but some 30% came from what is now northern France, southwest Germany and Italy.

The Conversation for more