by JOHN SMITH

Britain’s exit from the imperialist bloc known as the European Union (EU) is now irreversible. The crushing electoral defeat of the Labour Party has dismayed many workers and youth who had placed their hopes in Jeremy Corbyn, its left-wing leader. This article assesses these historic events, neither of which can be understood in isolation from the other.

Brexit

The United Kingdom is a declining imperial power comprising Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Right-wing politicians look everywhere except in the mirror for the causes of this decline, and hark to a time when Britain stood alone against the Nazi hordes and single-handedly rescued world civilisation, with some belated help from the USA. But this cherished national myth is a fantasy. The Nazi army’s back was broken on the eastern front, by the Soviet Union—not by Britain, which was busy fighting a colonial war in north Africa while the Soviet army and people were doing the heavy lifting. Britain’s losses at El Alamein, the biggest battle fought by the British Army before the Normandy landing in June 1944, were less than 2,000, while half a million Soviets died in the Battle of Stalingrad. Racism, hypocrisy and imperial hubris—core British values, in which all its political parties and institutions are steeped—explain the otherwise inexplicable madness known as Brexit.

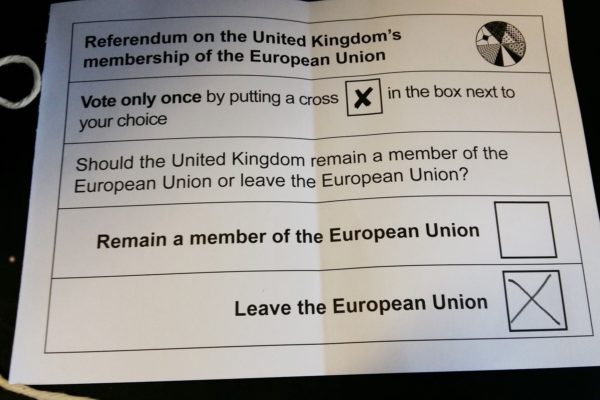

Imperial hubris notwithstanding, Britain’s capitalist rulers are confronted with a strategic dilemma: whether to ally with France and Germany in the EU, or to align with the USA—two directions equally inimical to the interests of workers and all oppressed people. Divisions within the ruling Conservative Party over this led in 2016 to a referendum in which voters decided, by a narrow margin, to leave the EU. In a previous article I explained why this outcome was determined by workers’ hostility to the EU—two thirds of workers voted to leave; and why the single-most important factor inducing them to do so was opposition to immigration—freedom of movement across the EU’s internal borders is one of the pillars of its free trade area, yet many workers suffering increasing insecurity and declining living standards blame these ills on increased competition from migrant workers and demand state protection against them.

During the three years of political turmoil following the 2016 referendum, the biggest obstacle to an orderly exit turned out to be the century-old partition of Ireland into the Irish Republic in the south and the British-occupied enclave in the north (see here for more on this). So long as both Britain and Ireland remain in the EU, people and goods can cross the border between the two parts of Ireland without even noticing, but the UK’s exit from the EU trade area would require the imposition of a hard border, dealing a severe blow to Ireland’s economy and risking reignition of armed struggle against the British occupation.

Former Prime Minister Theresa May negotiated an exit deal that evaded the border problem—by keeping both Britain and Northern Ireland inside the EU’s free trade zone until the conclusion of negotiations, yet to begin, on a permanent trade relationship; and a guarantee that, whatever its outcome, Northern Ireland would remain within the EU’s free trade zone and subject to its rules. May tried and failed three times to get this through Parliament, whereupon she resigned and Conservative party members, mostly rich white men over the age of 60, chose Boris Johnson as their leader.

Johnson duly reopened negotiations on the terms of the UK’s exit. As before, the EU insisted on a guarantee of no hard border between the two parts of Ireland. To the surprise of many (including this author), Johnson capitulated, agreeing a revised deal whose only substantial difference with the previous one is provision for a de facto permanent border between Britain and the whole of Ireland, while maintaining the pretence of UK constitutional integrity. In face of howls of betrayal from pro-imperialist Unionist politicians in Northern Ireland, Johnson flatly denied what was written in black and white in the deal he had negotiated, and rammed it through Parliament.

The December 2019 general election—fake democracy in action

As Johnson’s denials indicate, he has no intention of respecting the terms of the exit deal. His concession on the border question was entirely tactical—to get a deal through Parliament by any means and to then call a general election, in which the Conservative Party would campaign around a simple slogan: ‘Get Brexit Done’.

Monthly Review Online for more