Story by ADAM HOCHSCHILD

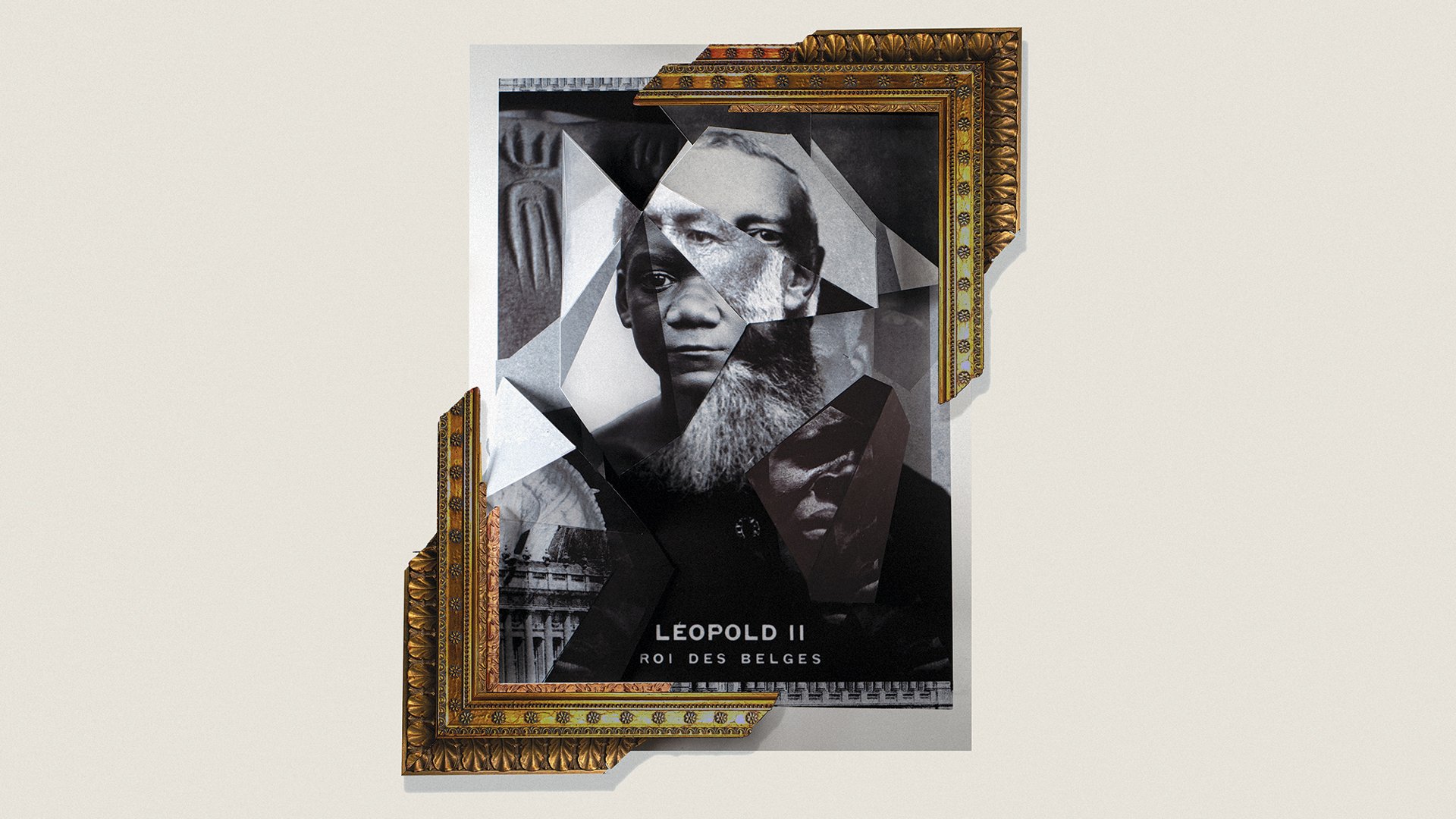

Textbooks can be revised, but historic sites, monuments, and collections that memorialize ugly pasts aren’t so easily changed. Lessons from the struggle to update the Royal Museum for Central Africa, outside Brussels.

One of Europe’s loveliest urban journeys begins as you step aboard a trolley at the Montgomery Metro station in Brussels. Its tracks quickly emerge from underground to travel along a grand, tree-shaded boulevard lined with elegant mansions a century old or more, many of them now embassies. Then the route leaves the street traffic behind to run through a leafy forest of beech and oak, a former hunting ground for the dukes of Brabant that becomes a symphony of fluttering green light on a spring day. Finally the tracks end near a palatial stone edifice whose very existence embodies some of the unresolved tensions of our globalized world.

To hear more feature stories, see our full list or get the Audm iPhone app.

Welcome to the Royal Museum for Central Africa. Although one of the largest museums anywhere devoted exclusively to Africa, it is thousands of miles from the continent itself. The tall windows, pillared facade, rooftop balustrade, and 90-foot-high rotunda of the main building give it the look of a chateau. That impression is only enhanced by an inner courtyard and a surrounding park: formal French gardens, a reflecting pool and fountain, ponds with ducks and geese, wide lawns laced with hedges, and carefully groomed paths that sweep away to majestic trees in the distance.

The Atlantic for more