by BRENDAN P. FOHT

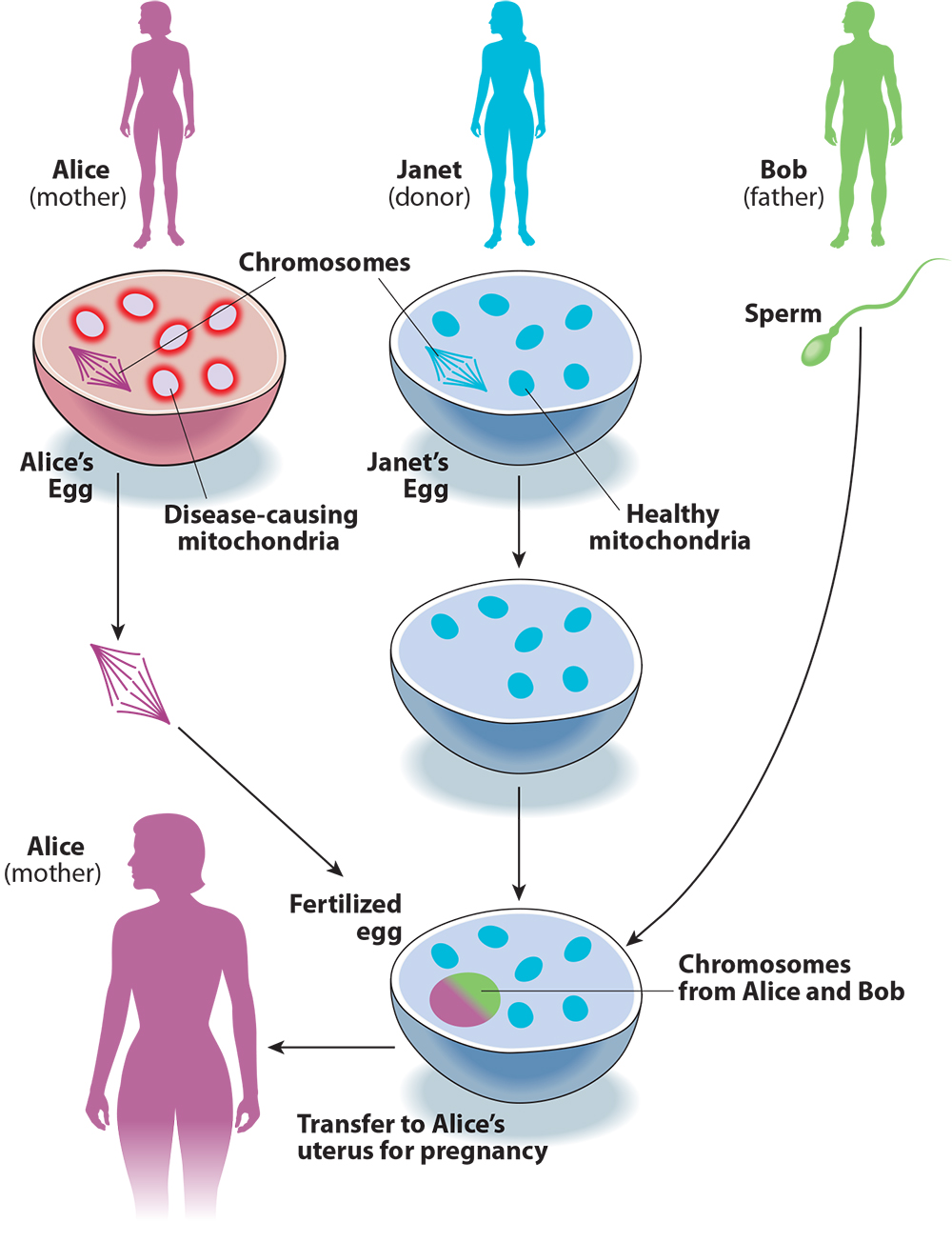

In three-parent IVF (here slightly simplified), a fertilized egg is created with material from three people: Alice, the mother, contributes chromosomes; Janet, a donor, contributes an egg cell with healthy mitochondria; and Bob, the father, contributes sperm. The resulting embryo is implanted in Alice’s womb.Steve Stankiewicz

Three-parent babies are being created not to prevent disease but to manufacture genetic relationships.

Debates about genetic engineering often invoke the concept of the “perfect child” — the prospect that parents will design future generations to accord with their ideals of appearance, intellect, or health. Yet what most every parent already considers “perfect” is his or her own child. Indeed, the creators of reproductive technology have already gone to great lengths to provide parents with their “own” genetic children. It can be easy to forget that it is this aim, rather than creating designer babies, that still dominates assisted reproductive technology today.

One recent innovation that illustrates the fertility industry’s efforts to establish genetic parenthood is a set of in vitro fertilization procedures that can create children with not two but three genetic parents. Scientists argue that these procedures, which they usually call mitochondrial replacement therapy, could help prevent certain kinds of genetic disease caused by mutations in a woman’s mitochondrial DNA.

The debate over so-called “three-parent babies” has largely been about whether these procedures constitute a defensible therapy or rather a heritable modification of the human germline — a radical transformation of human nature. For example, Shoukhrat Mitalipov, of Oregon Health and Science University, seems concerned mainly with warding off the specter of designer babies when he says of the procedure, “We don’t think this is modification. It’s not something that’s synthetic. It’s just taking a donor genome from somebody and replacing it with one that already exists. It’s natural.”

The trouble is that the conventional therapy-versus-modification framing, broadly accepted by critics and defenders alike, is miscast. As we will see, mitochondrial replacement therapy is not a true therapy, for it is not primarily aimed at preventing disease. But for the same reason, we can see that it is also not the kind of genetic engineering that could lead to designer babies. Instead, mitochondrial replacement is an extension of the many reproductive technologies that have been developed to help individuals and couples have children with specific kinds of biological and social relationships. We might call these technologies not genetic engineering but kinship engineering.

The New Atlantis for more