by VIJAY PRASHAD

News slips in from here and there in the northern hemisphere of outlandish temperatures. Records have been set; thermometers seem to need recalibration. Relief comes from the drop of a few degrees and from rainfall. But this is momentary. People are aware that the weather is more and more erratic, the heat of the summer much more brutal.

It is true that Europe faced remarkable temperatures in June, but the month before South Asia was hit by a severe heat wave. This is not a freak situation. India’s weather has been measured since the late 18th century. The records improved with the establishment of the Indian Meteorological Department in 1875. The summer has long been an incredibly hot time of the year, the monsoon rains anticipated like manna. Of the 15 hottest years on record, 11 of them have been recorded since 2004. This is a hint of evidence of the climate catastrophe.

Churu (in the state of Rajasthan) was the hottest town at 50.8°C (123.4°F). This is not far from the highest recorded temperatures on earth at Death Valley (California) and Mitribah (Kuwait) of 54.0°C. The government of India recorded an entire month’s worth of days (32) as having experienced heat waves.

In this period, India’s National Disaster Management Authority announced that at least 36 workers had burnt to death. The number is much lower than the 2,081 who died in a 2015 heat wave, although those who follow these calamities note that these numbers are very deflated.

Nine of ten Indian workers are in the informal sector, hundreds of millions of them in construction and agriculture. The most exploited of these workers toil in the hot sunshine, part of the frenzied expansion of India’s cities and part of the crisis-ridden agrarian sector. When these very poor workers die, few pay attention. Their deaths are often recorded not from heat stroke or exhaustion but as merely “unknown causes.”

Working on a Warmer Planet

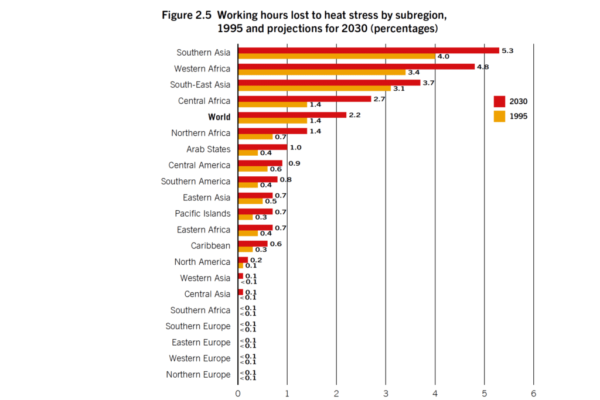

The International Labor Organization (ILO) has just released a brief—but very important—report on the impact of heat stress on workers. What the ILO finds is that the areas of the world most threatened by heat deaths of workers are Southern Asia and Western Africa. Agricultural and construction workers, the ILO says, are most vulnerable to death by rising temperatures.

If heat rises above 35°C, much less than the temperatures in central and northern India this year, then it “restricts a worker’s physical functions and capabilities” and—if it goes above 39°C—it can lead to “heat exhaustion” and death. What happens is that as temperatures rise, the body cannot endure this excess heat. This is what is known as “heat stress.”

A World Health Organization (WHO) report from 2014 points out that the health impact of the climate catastrophe will be caused by heat, coastal flooding, diarrheal disease, malaria, dengue and undernutrition. If you add all these up, then the WHO predicts excess mortality of at least a quarter of a million people per year. That heat is the first cause is not a surprise.

As a result of rising temperatures, global working hours have been lost—largely in agriculture and construction. According to the ILO calculations, the economic losses due to rising temperatures are going to grow. In 1995, an estimated $280 billion was lost due to heat stress; the ILO estimates that by 2030 that number will rise to $2.4 trillion. Most of these losses would occur in low-income countries.

Monthly Review Online for more