by ANDREW GASE

Is it possible to dig all the way through the Earth to the other side? Anishwar, age 8, India

When I was a kid, I liked to dig holes in my backyard in Cincinnati. My grandfather joked that if I kept digging, I would end up in China.

In fact, if I had been able to dig straight through the planet, I would have come out in the Indian Ocean, about 1,100 miles (1,800 kilometers) west of Australia. That’s the antipode, or opposite point on Earth’s surface, from my town.

But I only had a garden spade to move the earth. When I hit rock, less than 3 feet (1 meter) below the surface, I couldn’t go deeper.

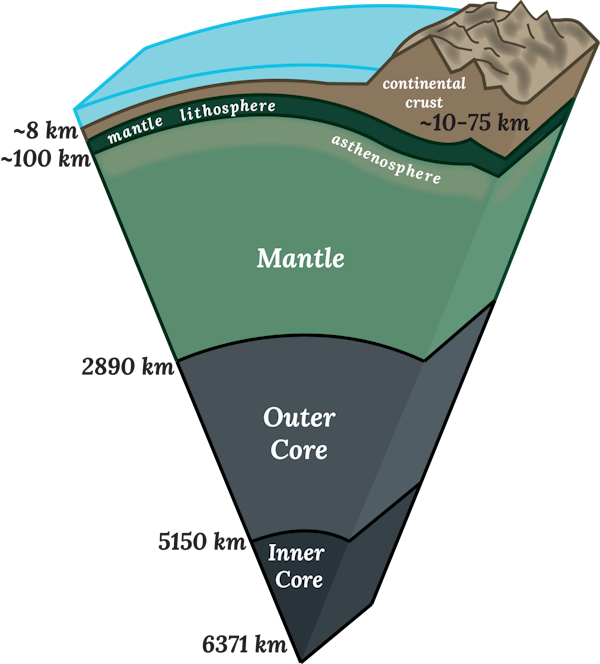

Now, I’m a geophysicist and know a lot more about Earth’s structure. It has three main layers:

- The outer skin, called the crust, is a very thin layer of light rock. Its thickness compared to Earth’s diameter is similar to how thick an apple’s skin is to its diameter. When I dug holes as a kid, I was scratching away at the very top of Earth’s crust.

- The mantle, which lies beneath the crust, is much thicker, like the flesh of the apple. It’s made of strong, heavy rock that flows up to a few inches per year as hotter rock rises away from Earth’s center and cooler rock sinks toward it.

- The core, at Earth’s center, is made of super-hot liquid and solid metal. Temperatures here are 4,500 to 9,300 degrees Fahrenheit (2,500 to 5,200 degrees Celsius).

Earth’s outer layers exert pressure on the layers underneath, and these forces increase steadily with depth, just as they do in the ocean – think of how pressure in your ears gets stronger as you dive deeper underwater.

That’s relevant for digging through the Earth, because when a hole is dug or drilled, the walls along the sides of the hole are under tremendous pressure from the overlying rock, and also unstable because there’s empty space next to them. Stronger rocks can support bigger forces, but all rocks can fail if the pressure is great enough.

When digging a pit, one way to prevent the walls from collapsing inward under pressure is to make them less steep, so they slant outward like the sides of a cone. A good rule of thumb is to make the hole three times wider than its depth.

Unstable walls

The deepest open pit in the Earth is the Bingham Canyon Mine in Utah, which was dug with excavators and explosives in the early 1900s to mine copper ore. The pit of the mine is 0.75 miles (1.2 kilometers) deep and 2.5 miles (4 kilometers) wide.

Since the mine is more than three times wider than it is deep and the walls are sloped, the pit’s walls are not too steep or unstable. Still, in 2013, one of the slopes collapsed, causing two huge landslides that released 145 million tons of crushed rock to the bottom of the pit. Luckily, no one was hurt, but the landslides caused hundreds of millions of dollars in damage.

The Conversation for more