by ROHAIT BHAGWANT

Dawn for more

by RAGIP SOYLU

Puntland’s President Said Abdullahi Deni turns Bosaso airport over to the United Arab Emirates without parliamentary approval

The United Arab Emirates deployed a military radar in Somalia’s Puntland earlier this year to defend Bosaso airport against potential Houthi attacks from Yemen, sources familiar with the matter told Middle East Eye.

Satellite imagery from early March reveals that the Israeli-made ELM-2084 3D Active Electronically Scanned Array Multi-Mission Radar was installed near the airport.

Publicly available air traffic data indicates that the UAE is increasingly using Bosaso airport to supply the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) in Sudan.

The RSF has been engaged in a war with the Sudanese military for two years.

Earlier this year, the Sudanese government filed a lawsuit against the UAE at the International Court of Justice, accusing it of genocide due to its links with the RSF. The UAE denies it backs the RSF militarily.

“The UAE installed the radar shortly after the RSF lost control of most of Khartoum in early March,” a regional source told MEE.

“The radar’s purpose is to detect and provide early warning against drone or missile threats, particularly those potentially launched by the Houthis, targeting Bosaso from outside.”

‘This is a secret deal, and even the highest levels of Puntland’s government, including the cabinet, are unaware of it’

– Somali source

Another regional source said the radar was deployed at the airport late last year. MEE was unable to independently verify this claim.

The second source said that the UAE has been using Bosaso airport daily to support the RSF, with large cargo planes regularly arriving to load weapons and ammunition – sometimes up to five major shipments at a time.

Middle East Eye for more

by EVAN BLAKE

On Tuesday, World Socialist Web Site International Editorial Board Chairman David North took part in a timely and urgent discussion with Professor Emanuele Saccarelli of San Diego State University’s Political Science Department, titled “It’s happening here: Fascism in 1933 Germany and today.”

Throughout the interview, North addressed questions that clarified the Marxist understanding of fascism, the historical processes that led to the rise of Hitler, the role of the working class in the fight against fascism, and the relevance of these lessons for today amid the Trump administration’s deepening efforts to establish a fascist dictatorship in the United States.

He underscored that the discussion of fascism is no longer merely historical but has “acquired intense contemporary relevance,” as many now ask whether the United States is confronted with fascism and what must be done to stop its advance.

When asked by Saccarelli to define fascism for a new generation entering political life, North stressed the necessity of a scientific and historical understanding, tracing the origins of fascism to the aftermath of the 1917 Russian Revolution and the wave of working class radicalization that followed the First World War. He emphasized that fascism arose as a mass movement mobilizing the petty bourgeoisie, demoralized workers and lumpen elements to smash the organizations of the working class, in the service of the big bourgeoisie.

North explained that Mussolini’s fascism in Italy and Hitler’s Nazism in Germany were direct responses to revolutionary threats from the working class. “The most distinctive element of Italian fascism was that it arose as a movement to suppress and beat back a radicalizing working class movement,” he said, noting that the failure of the socialist parties to lead the working class to power created the conditions for the rise of fascism. In Germany, the betrayal of the 1918-19 and 1923 revolutions by the Social Democratic and Communist parties gave the bourgeoisie time to regroup, paving the way for Hitler’s ascent.

Saccarelli asked North to address whether Hitler came to power through a putsch or democratic means and the implications for today. North responded: “As a matter of historical fact, Hitler did not come to power in a putsch. He had attempted a putsch in 1923—it was unsuccessful.” Rather, North explained, “German democracy was itself on its last legs,” with the government increasingly ruling by decree and the forms of parliamentary democracy hollowed out. Despite the Nazi Party becoming the largest in the Reichstag, Hitler never achieved a parliamentary majority; his rise was facilitated by the refusal of the two mass working class parties—the Social Democrats and Communists—to form a united front against fascism.

World Socialist Web Site for more

by DEEKSHA UDUPA

Nadine Strossen is a leading expert on constitutional law and civil liberties. She is the author of HATE: Why We Should Resist It with Free Speech, Not Censorship and Free Speech: What Everyone Needs to Know. She was previously the President of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and has testified before Congress on multiple occasions. She is a Senior Fellow with the Foundation for Individual Rights and Education (FIRE) and was named one of America’s “100 Most Influential Lawyers” by the National Law Journal.

In this interview, Strossen shares her insight on the power of “more speech” and “counter speech” as potential alternatives to effectively countering hate speech while highlighting the limitations and inefficacy of legal approaches.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Deeksha Udupa: In your work, you examine and unpack the “hate speech vs. free speech” framework largely in the U.S. context. How do you think this framework translates to other parts of the world, where hate speech rapidly leads to on-the-ground violence against minorities?

Nadine Strossen: The framework that the U.S. Supreme Court has crafted under the First Amendment of the Constitution has universal applicability because it is a framework that establishes general standards and principles. With that being said, the framework is extremely— and indeed completely— fact-specific and content-sensitive. I say this not as an imperialist American who thinks we know better than the rest of the world. I say this as someone who has studied various legal systems and talked to human rights activists around the world, and these activists also oppose censorship beyond the power that would exist under the U.S. First Amendment. They oppose this not because it is inconsistent with the laws of their own countries but because they believe that further censorship is ineffective in actually countering and changing hateful attitudes.

The basic standard under the U.S. First Amendment is also very strongly echoed in the International Free Speech law under the UN treaties, which various international free speech experts have studied and written about. There are two basic principles: first, speech may never be solely suppressed because one disapproves or even loathes the idea, content, and message behind the speech. This holds true even if the message is despicable or hateful. The answer is not government censorship and suppression. The second basic principle goes beyond the content of the message: if the speech directly causes or imminently threatens specific communities, then it can and should be suppressed.

I can think of many situations in less developed societies with more volatile social situations and less effective law enforcement where messages may satisfy the emergency standard in that context yet may not in the U.S. context. With that being said, the U.S. is a big place, and there are instances in the U.S. where hateful speech can and should be punished, like the 2017 white supremacist Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. These pro-racist, white supremacists came together and were chanting statements like “you will not replace us. Jews will not replace us.” These hateful statements alone could not be punished. Yet, considering these statements in the context of how they were marching towards a group of counter demonstrators—with lit tiki torches that they brought very close to [their] faces — that posed an immediate threat to the counter protesters which should’ve been punished.

To summarize, when there is a direct causal connection between speech and imminent violence such that other measures such as law enforcement, education or information are not enough to prevent violence, that speech should be punished. I say this with the recognition that this standard will be satisfied more often in many other countries than it would in the United States.

DU: Why do you think ‘hate speech’ laws have predominantly done more harm than good?

NS: My goal is to understand how we can resist hate. If I were convinced that more censorship effectively resisted hate, I would be in favor of it. One of my major international sources is called The Future of Free Speech, which is based at Vanderbilt University and founded by Jacob Mchangama. They have a very global perspective on free speech and have consistently shown that, at best, hate speech laws are ineffective in changing people’s perspectives and reducing discriminatory violence. At worst, they are counterproductive. The goal is to change people’s minds and perspectives: to enlighten them and broaden their understanding of other people. It is widely accepted that criminal law and a more punitive approach is ineffective in the U.S.

We need to move towards a restorative justice approach, where we root our work on how to constructively integrate people into our society. As I’ve said earlier, if the words are punishable under the First Amendment, then punishment is appropriate. We must also bear in mind, however, that it may not be the most effective approach to sentence someone under a hate speech or hate crime law and send them to prisons, where they are likely to have their hate views further reinforced and deepened. I have extensively read about people who were formerly members or even leaders of hateful organizations. They’ve been able to redeem themselves with the help of others— not others who are seeking to punish or shame them, but others who are reaching out with compassion and empathy for them as people.

Counterspeech, outreach, and empathy should not be reactive but proactive. It is too little too late if we wait until someone has actually committed an act of violence. That’s why I love the work that CSOH and other organizations are doing to take advantage of the powerful tool that is social media to do a lot of good. We are all aware of the great deal of harm that these platforms can do, but I also believe that they can do a lot of good. I am heartened by studies that show the positive effects of using tools like AI to proactively debunk disinformation, hate speech, and extreme content.

DU: If laws are not the solution, what alternative mechanisms do you propose for holding perpetrators of hate speech accountable, especially when it causes real-world harm?

by BINOY KAMPMARK

Universities are in a bind. As institutions of learning and teaching, knowledge learnt and taught should, or at the very least could, be put into practice. How unfortunate for rich ideas to linger in cold storage or exist as the mummified status of esoterica. But universities in the United States have taken fright at pro-Palestinian protests since October 7, 2023, becoming battlegrounds for the propaganda emissaries of Israeli public relations and the pro-evangelical, Armageddon lobby that sees the end times taking place in the Holy Land. Higher learning institutions are spooked by notions of Israeli brutality, and they are taking measures.

These measures have tended to be heavy handed, taking issue with students and academic staff. The policy has reached another level in efforts by amphibian university managers to ban various protest groups who are seen as creating an environment of intimidation for other members of the university tribe. That these protesters merely wish to draw attention to the massacre of Palestinian civilians, including women, children, and the elderly, and the fact that the death toll, notably in the Gaza Strip, now towers at over 50,000, is a matter of inconvenient paperwork.

Even worse, the same institutions are willing to tolerate individuals who have celebrated their own unalloyed bigotry, lauded their own racial and religious ideology, and deemed various races worthy of extinguishment or expulsion. Such a man is Israel’s National Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir, who found himself permitted to visit Yale University at the behest of the Jewish society Shabtai, a body founded by Democratic senator and Yale alumnus Cory Booker, along with Rabbi Shmully Hecht.

Shabtai is acknowledged as having no official affiliation with Yale, though it is stacked with Yale students and faculty members who participate at its weekly dinners. Its beating heart was Hecht, who arrived in New Haven after finishing rabbinical school in Australia in 1996.

The members of Shabtai were hardly unanimous in approving Ben-Gvir’s invitation. David Vincent Kimel, former coach of the Yale debate team, was one of two to send an email to a Shabtai listserv to express brooding disgruntlement. “Shabtai was founded as a space for fearless, pluralistic Jewish discourse,” the email remarks. “But this event jeopardizes Shabtai’s reputation and every future.” In views expressed to the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, Kimel elaborated: “I’m deeply concerned that we’re increasingly treating extreme rhetoric as just another viewpoint, rather than recognizing it as a distortion of constructive discourse.” The headstone for constructive discourse was chiselled sometime ago, though Kimel’s hopes are charming.

As a convinced, pro-settler fanatic, Ben-Gvir is a fabled-Torah basher who sees Palestinians as needless encumbrances on Israel’s righteous quest to acquire Gaza and the West Bank. Far from being alone, Ben-Gvir is also the member of a government that has endorsed starvation and the deprivation of necessities as laudable tools of conflict, to add to an adventurous interpretation of the laws of war that tolerates the destruction of health and civilian infrastructure in the Gaza Strip.

After a dinner at President Donald Trump’s Mar-a-Lago resort (the bad will be fed), Ben-Gvir was flushed with confidence. He wrote on social media of how various lawmakers had “expressed support for my very clear position on how to act in Gaza and that the food and aid depots should be bombed in order to create military and political pressure to bring our hostages home safely.” By any other standard, this was an admission to encouraging the commission of a war crime.

Dissident Voice for more

by PHAR KIM BENG

Family feud-fueled vote could herald Sara Duterte’s presidential rise and render Marcos Jr a lame duck with three years still in office

As the Philippines heads toward pivotal midterm elections on May 12, a dramatic political shift is underway.

Once considered the crown prince of dynastic restoration, President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr is now floundering, with his public approval rating plummeting from 42% in February to 25% in March, according to a Pulse Asia Research poll.

Meanwhile, Vice President Sara Duterte, daughter of the now-detained former strongman leader Rodrigo Duterte, is rising in the electorate’s eye, up from 52% in February to 59% in March, the same poll showed.

The arrest and extradition of Rodrigo Duterte to The Hague earlier this year on charges of crimes against humanity during his bloody war on drugs was a seismic moment in Philippine politics.

While many in the international community lauded the move as a step toward accountability for thousands of unpunished extrajudicial killings, its domestic reception has been mixed.

For many Filipinos, particularly in Mindanao and Duterte strongholds across the Visayas, the spectacle of a former president being tried abroad rather than at home has stirred nationalist resentment.

So far, it appears this Western international intervention, aided and abetted by Marcos Jr’s government, has bolstered, not weakened, Sara Duterte’s political standing.

She has deftly positioned herself as the inheritor of her father’s political mantle while avoiding his excesses. And the symbolism of her defending national sovereignty—by implication, if not explicitly—has endeared her to a Filipino public weary of foreign moralizing and elite Manila politics.

This puts the Marcos Jr administration in a bind. What was likely intended as a triumphant moment of legal reckoning has, in practice, sparked a backlash. In the eyes of many, the Hague trial is less about Rodrigo Duterte and more about a state that is increasingly perceived as unstable and externally manipulated.

The many reasons for Marcos Jr’s fading popularity are empirical and deeply felt on the ground. First, a cost-of-living crisis continues to batter ordinary Filipinos, with Rice, sugar, and basic utility prices all surging.

Asia Times for more

by DIANA CARIBONI

Attacking those searching for missing loved ones is ‘particularly despicable’ politics, says activist Lisa Sánchez

More than 5,600 mass graves have been found in Mexico since 2007, and there are more than 72,000 unidentified bodies in the country’s morgues, while 127,000 people are reported missing. Yet the state denies that disappearance is a systematic and widespread crime and stigmatises those who denounce it, Mexican activist and security researcher Lisa Sánchez told openDemocracy.

Enforced disappearance is not new in Mexico. But it has been normalised in part by the violence triggered by the militarisation of the ‘war on drugs’ – formally launched under the government of the right-wing National Action Party’s (PAN) Felipe Calderón between 2006 and 2012, and intensified by his successors.

The crime now has an impunity rate of 99%, explained Sánchez, the director general of Mexico United Against Crime (MUCD), a civil society organisation working on citizen security, justice and drug policy, in an interview held as the national and international conversation around Mexico’s disappearances intensified.

In recent weeks, the media circus surrounding the discovery of an alleged cartel training and extermination site in the state of Jalisco has led to a campaign of attacks on the families searching for their loved ones, which Sánchez described as “particularly despicable”.

And on 5 April, the UN Committee on Enforced Disappearances decided for the first time to open a procedure for the case of Mexico and activate Article 34 of the International Convention against Enforced Disappearances. This involves requesting further information from the government “on the allegations received, which in no way prejudges the next steps in the proceedings” and, eventually, referring the matter to the General Assembly. For the committee’s experts, who have been studying the case for a decade, there are indications of a “systematic and widespread” practice.

Mexico’s Senate responded by rejecting the committee’s decision and asking the UN to sanction its president, Olivier De Frouville – a response approved by the country’s ruling left-wing party, the National Regeneration Movement (usually referred to as Morena).

“The Senate vote made me lose a lot of my morale,” Sánchez said. The following is an excerpt from our interview, which has been translated into English and edited for length, clarity and style.

openDemocracy: In Latin America, disappearance is identified as a state crime committed by authoritarian governments in previous decades. Why are there so many disappeared people in Mexico in the current context?

Lisa Sánchez: Mexico is an exception in Latin America because, although it had an authoritarian government [ruled by the Institutional Revolutionary Party, PRI, between 1929 and 2000], it was not the result of a coup d’état, and therefore there was no military dictatorship. The disappearances that occurred in the 1960s and 1970s were considered a state crime at a time of political persecution of socialist dissidents, whom the PRI, allied with the United States, pursued very vigorously because it considered them a threat to national security.

Although the Mexican left always rejected these disappearances and considered them a state crime, we never had a process of memory recovery as part of our national debate. Much less did we punish the perpetrators, although in recent years we have inaugurated a couple of truth commissions on the crimes of the ‘dirty war’. But in reality, the disappearances never faced collective, real, large-scale and organised rejection, as they did in South America.

Do you see a link between the failure to acknowledge this past and this new type of disappearance in the context of drug-related violence?

In some ways, yes, and in some ways, no, but I bring it up because the fact that we didn’t go through revisiting that painful reality during our transition to democracy allowed our governments to continue with the narrative that it was not a state policy. And that’s problematic because it is what we are seeing today.

Open Demoracy for more

by JAWED NAQVI

What else was happening in the world when Mughals ruled India from 1526 till Aurangzeb’s death in 1707? The strange question flows from stranger demands by Hindu nationalists to raze his nondescript grave in Aurangabad.

Was he that evil? Should Britons then campaign to have the crypt of Henry VIII blown up for his ghastly abuse and murder of the hapless women he married? The psychopathic Briton was a contemporary of Babar and Humayun, India’s first Mughal rulers, one a poet as glimpsed in his fabled memoirs, the other an incorrigible mystic.

Hindutva ideologues have been traditionally incensed with India’s Muslim rulers, usually for no better reason than Hitler had for hating Jews or Netanyahu’s genocidal impulse towards Palestinians. Without softening their criticism for cruel rulers at home, the BJP might usefully ponder what they are missing out in their ideas about cruel usurpers. Let their hatred of Aurangzeb remain intact if it helps them take a cursory look at the time the Europeans arrived on American shores three decades ahead of Babar’s inauguration as India’s first Mughal king.

The European rulers authorised over 1,500 wars, attacks and raids on native Indians, said to be the most brutal of any country in the world against its indigenous people. According to historical accounts, by the close of the so-called ‘Indian Wars’ in the late 19th century, fewer than 250,000 Indigenous people remained from the estimated 10 million living in North America when Columbus arrived in 1492.

There was another event that took place in 1707, one that evidently remains more relevant for the world today than a dead Mughal emperor buried in a distant grave. England and Scotland united to create Great Britain that year. The marriage of convenience had reverberations across the Western world and impacted the consolidation of British rule in America. However, the forced union has been up for divorce ever since, surviving several close calls by nationalist Scots seeking independence. The Scots want to correct a historical wrong. What is the Hindu right hoping to achieve by digging up a 300-year-old grave?

True, Prime Minister Modi’s worldview regards Aurangzeb as an anti-Hindu zealot who imposed protection tax on non-Muslims. Fair enough. Professional historians don’t disagree that he had the narrowest of visions among the Mughals to rule a multicultural country like India. But historians also offer an opposite evidence, that of the Muslim ruler’s generous grants to Hindu temples even as he destroyed some others.

Truth be told, nobody was bothered by Aurangzeb or his grave till the BJP fanned it into a communal frenzy for its patently cynical politics. The party’s communal mobilisation was helped along by a dubious Hindi movie, applauded and backed by the Modi establishment. The movie Chaava depicts Aurangzeb’s brutal murder of Maratha warrior king Sambhaji but it ignores crucial bits of history to construct a communally polarising story, not the first in Hindutva’s quiver.

The question is who the ideal ruler was, which Aurangzeb was not. Some say it was Akbar, but the Hindu right hates him with often greater zeal.

Let’s grant for the sake of respite for Aurangzeb’s charged up critics that the Mughal emperor was a terrible ruler. He killed his religiously eclectic elder brother Dara Shikoh to ascend the throne. He fought peasant rebellions led by Sikhs, Marathas and Jats.

Dawn for more

EUROPEAN LEFT

The European Left Party stands with the people of Serbia in their struggle against an increasingly authoritarian regime.

Since 2014, Aleksandar Vucic and his Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) have embarked on a deliberate and calculated campaign to consolidate power, stifle dissent, and enrich their cronies. Opposition parties have been systematically undermined, public media has been transformed into a propaganda arm of the state, and a suffocating monopoly over the public sphere has been established, effectively silencing critical voices and limiting the space for independent thought.

Likewise, the December 2023 elections were marred by credible and widespread allegations of voter migration and manipulation, casting a dark shadow over the legitimacy of the electoral process and raising serious questions about the integrity of Serbia’s democratic institutions.

This concentration of power, coupled with rampant corruption and economic exploitation, has created a climate of fear, impunity, and widespread disillusionment. The regime is deeply entangled with a network of unscrupulous businessmen and companies, that are siphoning off state funds through corrupt practices, enriching themselves at the expense of the Serbian people and perpetuating a system of inequality and injustice.

Civil society organizations, the lifeblood of a healthy democracy, have been targeted with raids, intimidation, and smear campaigns. Independent media outlets, essential for holding power accountable, have been subjected to relentless attacks and disinformation campaigns, aimed at discrediting protesters and silencing critical voices.

We are deeply concerned by credible reports of violence and intimidation tactics used against protesters, including the infiltration of demonstrations by government agents provocateurs and the deployment of hooligans and criminal elements to sow chaos, fear, and division.

The government’s continued failure to provide full transparency regarding the tragic collapse of a railway station canopy in Novi Sad, further underscores its callous disregard for accountability, transparency, and the well-being of its citizens. This tragedy serves as a stark reminder of the human cost of corruption and negligence.

European Left for more

by WILLIAM WRIGHT & TAKAKI KOMIYAMA

Every day, people are constantly learning and forming new memories. When you pick up a new hobby, try a recipe a friend recommended or read the latest world news, your brain stores many of these memories for years or decades.

But how does your brain achieve this incredible feat?

In our newly published research in the journal Science, we have identified some of the “rules” the brain uses to learn.

Learning in the brain

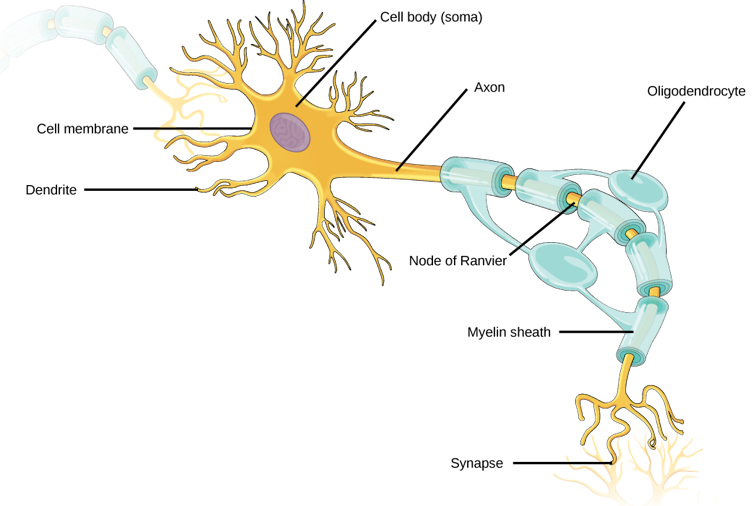

The human brain is made up of billions of nerve cells. These neurons conduct electrical pulses that carry information, much like how computers use binary code to carry data.

These electrical pulses are communicated with other neurons through connections between them called synapses. Individual neurons have branching extensions known as dendrites that can receive thousands of electrical inputs from other cells. Dendrites transmit these inputs to the main body of the neuron, where it then integrates all these signals to generate its own electrical pulses.

It is the collective activity of these electrical pulses across specific groups of neurons that form the representations of different information and experiences within the brain.

How The Conversation is different: We explain without oversimplifying.

For decades, neuroscientists have thought that the brain learns by changing how neurons are connected to one another. As new information and experiences alter how neurons communicate with each other and change their collective activity patterns, some synaptic connections are made stronger while others are made weaker. This process of synaptic plasticity is what produces representations of new information and experiences within your brain.

In order for your brain to produce the correct representations during learning, however, the right synaptic connections must undergo the right changes at the right time. The “rules” that your brain uses to select which synapses to change during learning – what neuroscientists call the credit assignment problem – have remained largely unclear.

Defining the rules

We decided to monitor the activity of individual synaptic connections within the brain during learning to see whether we could identify activity patterns that determine which connections would get stronger or weaker.

The Conversation for more